Town Pond: Area of early settlement.

Anne Hutchinson only lived in Portsmouth for four years, but her story is pivotal to understanding the founding of our town. Anne was a bold and intelligent woman that the ministers of Boston viewed as a threat to their power and to the community as a whole. Boston was a theocracy where the church and the state were so connected that you had to be a church member to be able to vote. Anne was a critic of the ministers and to stop her influence she was put on trial twice. Her civil trial was in Fall of 1637 and her church trial was in March of 1638. Anne’s greatest crime was leading weekly public meetings to discuss scripture, theology and the ministers’ sermons. In 1635 she started with just women, but by 1636 men began to accompany wives. Anne had stepped out of place.

Among her followers were some of our prominent town founders. Many of them were solid citizens in Boston. William Aspinwall was a notary, court recorder, and surveyor. William Coddington was the richest man in Boston. John Coggeshall was a silk merchant. William Baulston was an innkeeper. William Dyer was a milliner. As Anne was tried in court, her followers were removed from positions in town government, deprived of their weapons and expelled from Boston as well. John Clarke had not been part of Hutchinson’s followers, but he joined the group leaving with Anne because he was interested in a society where freedom of religion was possible. The men in Hutchinson’s group wanted to create a settlement with freedom of conscience. Roger Williams, who had been expelled from Boston earlier, urged them to try Aquidneck Island. Men packed building supplies in a ship they had hired to sail them around Cape cod.

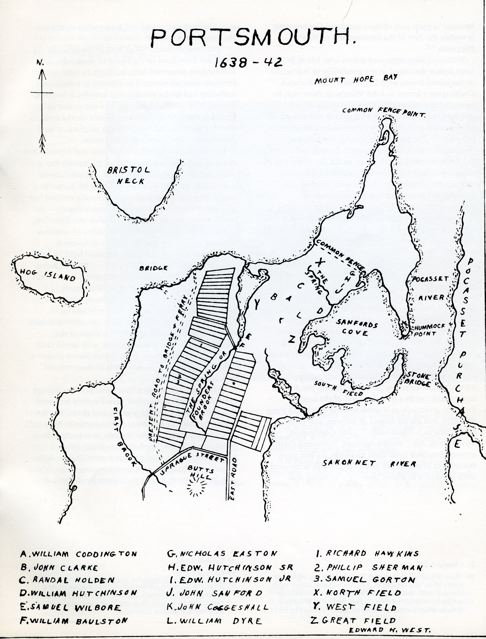

About March 7, while in Boston, a group of men signed what is now known as the Portsmouth Compact. It was an agreement to join together as a “Bodie Politik.” Will and Edward Hutchinson (Anne’s son) traveled to Providence to Roger Williams who arranged a meeting with Narragansett Sachems Miantonomo and Canonicus. On March 24th they gave the sachems “a gratuity” of forty fathoms of white wampum beads, ten coats, and twenty hoes. Randall Holden represented the Hutchinson group. The men continued south on ships to a new home Aquidneck Island in Narragansett Bay. They agreed to make the first settlement on the flat northeastern end which had a natural spring saltwater cove. Their first homes resembled what the Native Americans used. They pitched tents and built huts to live in while they cleared land. The men chose two to three acre house lots between the cove and spring and began framing simple houses.

Anne walked from Boston to Portsmouth. On April 1, 1638 she began a six day walk. With her were son Edward (24), Bridget (19), Francis (17), Anne (12), Mary (10), Katherine (8), William (6), Susan (4 and a half), Zuriel (2). Anne’s daughter Bridget carried month old son Eliphal. They walked from Wollaston to Quincy, through Braintreee, Brockton, Tauton, Pawtucket. They slept in wigwams and makeshift shelter along the way to Providence. Providence had about a hundred settlers at the time and was a maritime center. The group with Anne traveled the last sixteen miles by ship to Aquidneck.

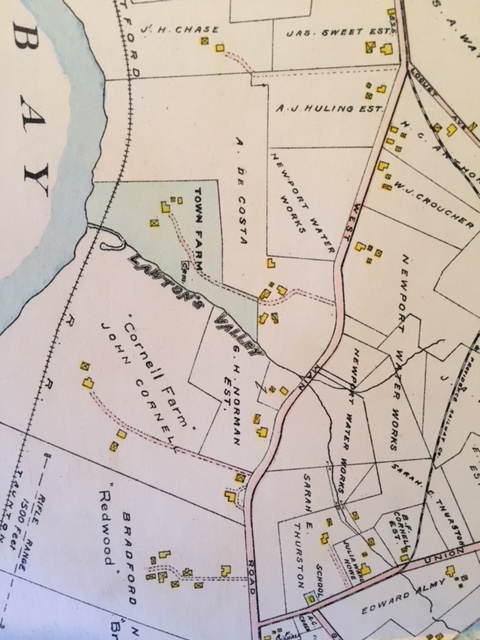

Portsmouth was so much more primitive than the Boston they ha left. The first settlement was about sixty to seventy people. They lived in pits dug in the ground with floors of planks and dirt walls covered with tree bark. They had two or three acre house lots between great cove and mount hope bay. The Hutchinson lot was on the western beach of the cove.

A short while after they settled there was an earthquake that shook the community. Governor Winthrop said was “God’s continued disquietude against the existence of Anne Hutchinson”.

Anne had been pregnant during the trials and journey. She was delivered of what we know today was a hydatidiform mole or abnormal growth. Anne bled profusely and was attended to by John Clarke who was a physician. Somehow word got back to Governor John Winthrop in Boston. He asked Clarke for details and Clarke provided all the gory details. Abnormal births were considered judgements from God and women were accused of evil when such a birth occurred. Anne herself had helped Mary Dyer at the birth of a deformed baby before her trial.

Very little is know about Anne’s life here in Portsmouth. Did Anne continue to lead her meetings in Portsmouth? No formal churches were formed on the island at this early settlement time. John Clarke preached in Portsmouth but no church founded or built. Settlers were split over whether to gather on Lord’s day so religious services were disorganized at best. With all the problems they had with the Boston theocracy, this loose faith community might have been purposeful. Anne probably preached and gathered women at meetings. There was rapidgrowth in the community due to Anne’s influence and Boston’s strict theocracy.

When Anne’s husband William died, the Boston leaders were prepared to intimidate Anne again. Ministers from Boston came and suggested they would take over Rhode Island. Without William, Anne was vulnerable. In the summer of 1642, the fifty one year old widow was packing to move away from Portsmouth to New York. Her furniture and heavy belongings were sent over land along with horses, cattle, hogs. She hired boats to transport her group of family and friends (sixteen in all) to a new home. In August of 1643, Anne and most of her family were butchered in an attack. Only daughter Susan (Susanna) survived and she spent eight or nine years with the Siwanoy tribe.

Although Anne’s stay in Portsmouth was only four years, Portsmouth remains part of her legacy. We were founded by Anne and her followers and they brought a tradition of religious toleration with them.

Sources include: American Jezebel: The Uncommon Life of Anne Hutchinson, the Woman who defied the Puritans – by Eve LaPlante – Harper Collins, 2004

SaveSave

Rebecca Cornell’s mysterious death in 1673 has been the subject of stories, books and even a play. We know the story of how her brother, John Briggs, described a dream which called into question the cause of her fiery death. Her son, the junior Thomas Cornell, was ultimately hung for what was judged a murder. Rebecca Cornell, however, had another claim to fame. Rebecca was a friend of Anne Hutchinson and she was one of Portsmouth’s founding mothers.

Rebecca Cornell’s mysterious death in 1673 has been the subject of stories, books and even a play. We know the story of how her brother, John Briggs, described a dream which called into question the cause of her fiery death. Her son, the junior Thomas Cornell, was ultimately hung for what was judged a murder. Rebecca Cornell, however, had another claim to fame. Rebecca was a friend of Anne Hutchinson and she was one of Portsmouth’s founding mothers. In the Massachusetts Bay Colony, the role of midwife came with its own perils. In 1637 Jane Hawkins, the wife of Richard Hawkins, found herself in trouble after helping Mary Dyer deliver a “monster” stillborn child. The deformed baby was considered a sign of God’s punishment for the way Anne Hutchinson and her followers were criticizing the ministers. According to Massachusetts Governor John Winthrop, “the midwife, presently after this discovery (of the deformed fetus) went out of the jurisdiction; and indeed it was time for her to be gone, for it was know, that she used to give young women oil of mandrakes and other stuff to cause conception; and she grew into great suspicion to be a witch, for it was credibly reported, that, when she gave any medicines (for she practiced physic), if she did believe, she could help her. (Winthrop’s Journal April 1638).

In the Massachusetts Bay Colony, the role of midwife came with its own perils. In 1637 Jane Hawkins, the wife of Richard Hawkins, found herself in trouble after helping Mary Dyer deliver a “monster” stillborn child. The deformed baby was considered a sign of God’s punishment for the way Anne Hutchinson and her followers were criticizing the ministers. According to Massachusetts Governor John Winthrop, “the midwife, presently after this discovery (of the deformed fetus) went out of the jurisdiction; and indeed it was time for her to be gone, for it was know, that she used to give young women oil of mandrakes and other stuff to cause conception; and she grew into great suspicion to be a witch, for it was credibly reported, that, when she gave any medicines (for she practiced physic), if she did believe, she could help her. (Winthrop’s Journal April 1638). The founding mothers of Portsmouth and Aquidneck Island were a brave lot. What conditions did they face when they came to settle here?

The founding mothers of Portsmouth and Aquidneck Island were a brave lot. What conditions did they face when they came to settle here?