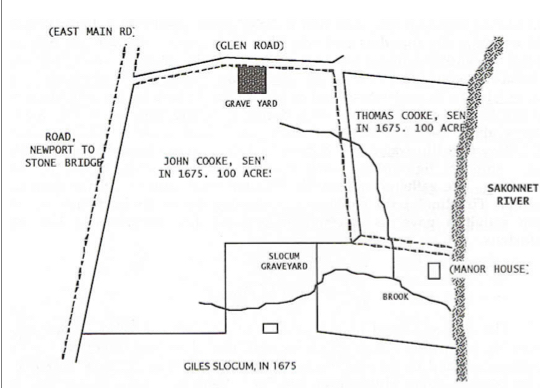

Rebecca Cornell, a 73 year old widow, lived in her 100-acre home in Portsmouth with her son Thomas; his second wife Sarah; their two daughters; his four sons from his first marriage; a male lodger and a male servant.

Late afternoon on Feb 8, 1673, Thomas arrived home to find his mother feeling ill. Family members kept her company; Thomas talked with her for ninety minutes, but left at 7:00 p.m. to wind a “Quill of Yarn” before supper. Rebecca didn’t join the family supper because she didn’t want the “salt-mackrill” meal. About 45 minutes later grandson Edward went to her room to ask her if she wanted something else to eat. Seeing flames, he ran out to get a candle. Meanwhile, everyone ran into Rebecca’s room, where she was burned beyond recognition.

Two nights later Rebecca’s ghost paid a surprise visit to her brother, John Briggs, a 64-year old grandfather. He reported that on seeing the shape of a woman by his bedside, he “cryed out, in the name of God what art thou…” The apparition replied, “I am your sister Cornell, and Twice sayd, see how I was Burnt with fire.” A later autopsy showed “A Suspitious wound on her in the upper-most part of the Stomake.”

Circumstantial evidence was stacked against Thomas. There were bad feelings between mother and son because she’d given him her estate but he had to divide 100 pounds among his siblings and he had to care for his mother. His temper, which Rebecca told people she feared, didn’t help.

There was also tension between Rebecca and daughter-in-law Sarah. Thomas had motive to murder. He also had access to a purported murder weapon, “sume instrumen licke or the iron spyndell of a spinning whelle.” And he was the last person to see Rebecca alive. Thomas Cornell, 46, was hung for her “murder” on May 23, 1673.

Who were the other suspects, if it was murder? Two doors gave access to Rebecca’s downstairs bedroom. Unrest existed between Europeans settlers and the Indians. An Indian named Wickhopash (a.k.a. Harry) had a motive for the crime. He’d been on “the losing end of criminal action for grand larceny brought by Thomas in June 1671” and had received a punishment. Often Indian revenge was taken out by attacking lone female family members, and arson was their tactic. In 1674 he was tried and acquitted for the killing.

In 1675 Thomas’s younger brother, William, presented persuasive evidence that Sarah had a role in Rebecca’s death. She was burdened with “catering to her demanding mother-in-law,” and she had a violent streak. She too was acquitted.

The theory of accidental death also remains. Rebecca might have tried making her own fire, caught herself on fire, fallen and dragged herself away from the hearth. She’d also confided in her daughter Rebecca that she’d considered suicide three times.

So whodunit? Was it murder? An accident? Or suicide? Sarah birthed Thomas’s last child, a daughter she named Innocent, after his hanging.

Sources:

Crane, Elaine F. Killed Strangely: The death of Rebeka Cornell. Ithaca: Cornell Univ. Press, 2002

Rebecca Cornell, a 73 year old widow, lived in her 100-acre home in Portsmouth with her son Thomas; his second wife Sarah; their two daughters; his four sons from his first marriage; a male lodger and a male servant.

Late afternoon on Feb 8, 1673, Thomas arrived home to find his mother feeling ill. Family members kept her company; Thomas talked with her for ninety minutes, but left at 7:00 p.m. to wind a “Quill of Yarn” before supper. Rebecca didn’t join the family supper because she didn’t want the “salt-mackrill” meal. About 45 minutes later grandson Edward went to her room to ask her if she wanted something else to eat. Seeing flames, he ran out to get a candle. Meanwhile, everyone ran into Rebecca’s room, where she was burned beyond recognition.

Two nights later Rebecca’s ghost paid a surprise visit to her brother, John Briggs, a 64-year old grandfather. He reported that on seeing the shape of a woman by his bedside, he “cryed out, in the name of God what art thou…” The apparition replied, “I am your sister Cornell, and Twice sayd, see how I was Burnt with fire.” A later autopsy showed “A Suspitious wound on her in the upper-most part of the Stomake.”

Circumstantial evidence was stacked against Thomas. There were bad feelings between mother and son because she’d given him her estate but he had to divide 100 pounds among his siblings and he had to care for his mother. His temper, which Rebecca told people she feared, didn’t help.

There was also tension between Rebecca and daughter-in-law Sarah. Thomas had motive to murder. He also had access to a purported murder weapon, “sume instrumen licke or the iron spyndell of a spinning whelle.” And he was the last person to see Rebecca alive. Thomas Cornell, 46, was hung for her “murder” on May 23, 1673.

Who were the other suspects, if it was murder? Two doors gave access to Rebecca’s downstairs bedroom. Unrest existed between Europeans settlers and the Indians. An Indian named Wickhopash (a.k.a. Harry) had a motive for the crime. He’d been on “the losing end of criminal action for grand larceny brought by Thomas in June 1671” and had received a punishment. Often Indian revenge was taken out by attacking lone female family members, and arson was their tactic. In 1674 he was tried and acquitted for the killing.

In 1675 Thomas’s younger brother, William, presented persuasive evidence that Sarah had a role in Rebecca’s death. She was burdened with “catering to her demanding mother-in-law,” and she had a violent streak. She too was acquitted.

The theory of accidental death also remains. Rebecca might have tried making her own fire, caught herself on fire, fallen and dragged herself away from the hearth. She’d also confided in her daughter Rebecca that she’d considered suicide three times.

So whodunit? Was it murder? An accident? Or suicide? Sarah birthed Thomas’s last child, a daughter she named Innocent, after his hanging.

Sources:

Crane, Elaine F. Killed Strangely: The death of Rebeka Cornell. Ithaca: Cornell Univ. Press, 2002

A Portsmouth Ghost Story

October 31, 2018

Rebecca Cornell, a 73 year old widow, lived in her 100-acre home in Portsmouth with her son Thomas; his second wife Sarah; their two daughters; his four sons from his first marriage; a male lodger and a male servant.

Late afternoon on Feb 8, 1673, Thomas arrived home to find his mother feeling ill. Family members kept her company; Thomas talked with her for ninety minutes, but left at 7:00 p.m. to wind a “Quill of Yarn” before supper. Rebecca didn’t join the family supper because she didn’t want the “salt-mackrill” meal. About 45 minutes later grandson Edward went to her room to ask her if she wanted something else to eat. Seeing flames, he ran out to get a candle. Meanwhile, everyone ran into Rebecca’s room, where she was burned beyond recognition.

Two nights later Rebecca’s ghost paid a surprise visit to her brother, John Briggs, a 64-year old grandfather. He reported that on seeing the shape of a woman by his bedside, he “cryed out, in the name of God what art thou…” The apparition replied, “I am your sister Cornell, and Twice sayd, see how I was Burnt with fire.” A later autopsy showed “A Suspitious wound on her in the upper-most part of the Stomake.”

Circumstantial evidence was stacked against Thomas. There were bad feelings between mother and son because she’d given him her estate but he had to divide 100 pounds among his siblings and he had to care for his mother. His temper, which Rebecca told people she feared, didn’t help.

There was also tension between Rebecca and daughter-in-law Sarah. Thomas had motive to murder. He also had access to a purported murder weapon, “sume instrumen licke or the iron spyndell of a spinning whelle.” And he was the last person to see Rebecca alive. Thomas Cornell, 46, was hung for her “murder” on May 23, 1673.

Who were the other suspects, if it was murder? Two doors gave access to Rebecca’s downstairs bedroom. Unrest existed between Europeans settlers and the Indians. An Indian named Wickhopash (a.k.a. Harry) had a motive for the crime. He’d been on “the losing end of criminal action for grand larceny brought by Thomas in June 1671” and had received a punishment. Often Indian revenge was taken out by attacking lone female family members, and arson was their tactic. In 1674 he was tried and acquitted for the killing.

In 1675 Thomas’s younger brother, William, presented persuasive evidence that Sarah had a role in Rebecca’s death. She was burdened with “catering to her demanding mother-in-law,” and she had a violent streak. She too was acquitted.

The theory of accidental death also remains. Rebecca might have tried making her own fire, caught herself on fire, fallen and dragged herself away from the hearth. She’d also confided in her daughter Rebecca that she’d considered suicide three times.

So whodunit? Was it murder? An accident? Or suicide? Sarah birthed Thomas’s last child, a daughter she named Innocent, after his hanging.

Sources:

Crane, Elaine F. Killed Strangely: The death of Rebeka Cornell. Ithaca: Cornell Univ. Press, 2002

Rebecca Cornell, a 73 year old widow, lived in her 100-acre home in Portsmouth with her son Thomas; his second wife Sarah; their two daughters; his four sons from his first marriage; a male lodger and a male servant.

Late afternoon on Feb 8, 1673, Thomas arrived home to find his mother feeling ill. Family members kept her company; Thomas talked with her for ninety minutes, but left at 7:00 p.m. to wind a “Quill of Yarn” before supper. Rebecca didn’t join the family supper because she didn’t want the “salt-mackrill” meal. About 45 minutes later grandson Edward went to her room to ask her if she wanted something else to eat. Seeing flames, he ran out to get a candle. Meanwhile, everyone ran into Rebecca’s room, where she was burned beyond recognition.

Two nights later Rebecca’s ghost paid a surprise visit to her brother, John Briggs, a 64-year old grandfather. He reported that on seeing the shape of a woman by his bedside, he “cryed out, in the name of God what art thou…” The apparition replied, “I am your sister Cornell, and Twice sayd, see how I was Burnt with fire.” A later autopsy showed “A Suspitious wound on her in the upper-most part of the Stomake.”

Circumstantial evidence was stacked against Thomas. There were bad feelings between mother and son because she’d given him her estate but he had to divide 100 pounds among his siblings and he had to care for his mother. His temper, which Rebecca told people she feared, didn’t help.

There was also tension between Rebecca and daughter-in-law Sarah. Thomas had motive to murder. He also had access to a purported murder weapon, “sume instrumen licke or the iron spyndell of a spinning whelle.” And he was the last person to see Rebecca alive. Thomas Cornell, 46, was hung for her “murder” on May 23, 1673.

Who were the other suspects, if it was murder? Two doors gave access to Rebecca’s downstairs bedroom. Unrest existed between Europeans settlers and the Indians. An Indian named Wickhopash (a.k.a. Harry) had a motive for the crime. He’d been on “the losing end of criminal action for grand larceny brought by Thomas in June 1671” and had received a punishment. Often Indian revenge was taken out by attacking lone female family members, and arson was their tactic. In 1674 he was tried and acquitted for the killing.

In 1675 Thomas’s younger brother, William, presented persuasive evidence that Sarah had a role in Rebecca’s death. She was burdened with “catering to her demanding mother-in-law,” and she had a violent streak. She too was acquitted.

The theory of accidental death also remains. Rebecca might have tried making her own fire, caught herself on fire, fallen and dragged herself away from the hearth. She’d also confided in her daughter Rebecca that she’d considered suicide three times.

So whodunit? Was it murder? An accident? Or suicide? Sarah birthed Thomas’s last child, a daughter she named Innocent, after his hanging.

Sources:

Crane, Elaine F. Killed Strangely: The death of Rebeka Cornell. Ithaca: Cornell Univ. Press, 2002

Portsmouth Farm Heritage: What a Death Inventory Tells Us about Farming

October 27, 2018

Farm Heritage, Glen Area, Portsmouth History Leave a comment

Portsmouth Farm Heritage: Colonial Farmers

October 21, 2018

Portsmouth History Leave a comment

By 1657 most of the open land in Portsmouth was given out to freemen and inhabitants. Though Newport welcomed new settlers, Portsmouth residents were more guarded in accepting new residents. Settlers were not admitted without a vote of the town citizens. Once someone was accepted as a freeman, the town took responsibility to help them in time of need. Some colonists were given as much as 300 acres of pastureland.

There was a rule that farmers had to fence planting areas and orchards. They used stonewalls, rail fences and hedges as fences. We can still see stonewalls that mark the gardens and orchards of the old farms. By 1713 the final acres of town land were given out. This time freemen received twelve acres. In 1755 there were 1363 Portsmouth residents. Most of them were farmers. Farming continued to be an important part of Portsmouth life during colonial times. Newport was a good market for Portsmouth farm produce, but Portsmouth farmers sold their products all along the East Coast. Animals were very important to the colonial farmers. The cattle herds did well and soon Portsmouth cattle were being sold to Boston and the Barbados in the Caribbean. Large flocks of sheep and herds of horses were common.

Mills developed to help farmers. Saw mills started as early as 1642 to saw lumber for fences and houses. Grinding corn meal was very important to farmers and early water powered gristmills began in Lawton Valley and the Glen. By 1668 the first of many Portsmouth windmills was built on the Briggs Farm. This is the Butt’s Hill area and was commonly called “Windmill Hill.”

Portsmouth Farm Heritage: Settler/Farmers

October 16, 2018

Portsmouth History Leave a comment

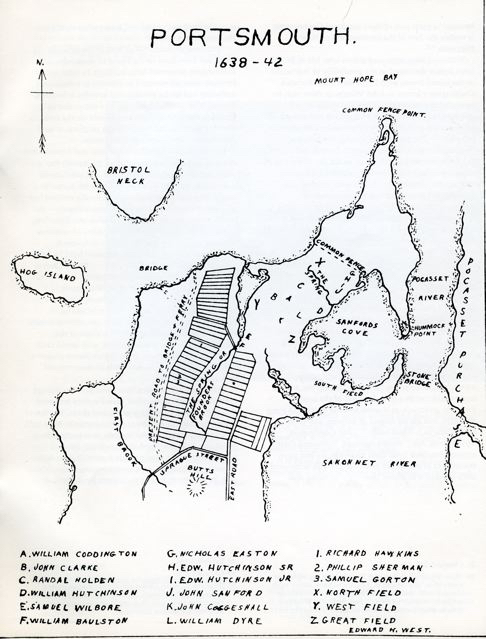

As the spring of 1638 came, the little band of founding settlers began their journey to Aquidneck Island. Some came over the land by way of Providence. Others sailed around Cape Cod. They settled at the North end of the Island around Founder’s Brook and another brook in the area. They had left the security of Boston for tent like homes or dug out caves lined with wood. Just like the Native Americans before them, they hunted and fished for food and they began to prepare the land for planting. There was a new community on Aquidneck Island beginning as the old native community had ended.

Portsmouth has always been known for its farming, but the original settlers had little experience in farming when they came here. They were craftsmen and tradesmen.

William Coddington was a merchant, William and Edward Hutchinson had a textile business, John Coggeshall was a clothier, William Dyer was a milliner and fishmonger, William Baulston was an innkeeper, Nicholas Easton was a tanner.

They had some experience with how land had been laid out in Boston, so they followed similar patterns here. The house lots were clustered together with open fields around them. Early town records show they were concerned about how land would be given out and that records of land ownership should be kept. They lived in the area between East and West Main roads from Sprague Street to the Mount Hope Bay. At first they were given two acre house lots near a spring and larger areas of grazing land further south from the settlement.

The first settlers brought cattle with them. There was a common pasture for cattle in the area that became known as Common Fence Point. All the settlers contributed to the cost of building and maintaining the fence. This pattern of houses together with town planting fields around them was a practical solution for the settlers. They didn’t yet have enough tools or time to clear land for planting nor did they have the plows or other equipment for planting and harvesting crops. Later on the house lots were given up as families began to live on their farms instead of together in a community. Caring for their animals and property became a real need. Soon the pigs and other animals became a problem as they trampled over the fields that had been planted. The grass on Hog Island was given to Portsmouth settlers and pigs roamed freely on Hog, Patience and Prudence Islands. Massasoit had granted grazing rights in the Fogland area of what is now Tiverton in exchange for wampum.

Portsmouth Farm Heritage:

October 14, 2018

Portsmouth History Leave a comment

Wampanoag Gardening

Portsmouth history is farm history and we will be exploring that history in blog posts to come. Our farm history starts with the fact that Aquidneck Island was a summer campground and hunting field for both Wampanoag and Narragansett tribes. We know something about how the island’s first residents grew their crops through the heritage of Wampanoag Three Sisters Gardening. URI Master Gardeners working at Prescott Farm created a Three Sisters Garden in back of the Sherman Windmill. Just a week ago I saw the corn stalks, squash and green beans there.

Green beans growing on corn stalks at Prescott Farm

How did our native residents feed their families? They hand planted seeds in a mound pattern about 18 inches at the base and 10 inches at a flat top where the corn would be planted. The mounds are about 4 inches high with a shallow ring around it to hold water. When the corn reaches about 4 inches high, beans are planted in four holes around the corn mound. Squash (summer, winter, pumpkin) is planted with the beans. The beans, corn and squash all help each other grow. The beans grow up the corn stalks and the squash spread out and help prevent weeds.

We associate the Wampanoags with our Thanksgiving, but in their calendar they have five thanksgivings. Strawberry Thanksgiving greets summer when the first wild berries ripen. Green bean thanksgiving and green corn thanksgiving are held in mid summer. Cranberry Thanksgiving celebrates the ripening of that berry in the Fall. After all the work is done there is yet another thanksgiving.  Wampanoag Calendar

Wampanoag Calendar