Today we think of Redwood Farms as a neighborhood in Portsmouth by West Main Road and Union Street. In colonial days this area was the country home of the Redwood family We know the Redwood name from the famed Redwood Library in Newport.

Abraham Redwood Sr. made his way to Aquidneck Island by way of Bristol, England, Antigua and Salem, Massachusetts. He settled in Newport. Born in Bristol, England, in 1665, he came into possession (by marriage) of a large sugar-plantation in Antigua, known as Cassada Garden. He resided there until 1712, when he moved to the British American colonies. After spending a few years in Salem, he settled permanently in Newport, Rhode Island.

His son (Abraham, Jr.) was born in Antiqua in 1710. He was sent to school in Philadelphia and returned to Newport before he was 18. Soon after he married Martha Coggeshall, a Quaker and a decendent of John Coggeshall, a founder of Portsmouth.

Abraham Redwood, Jr. inherited the Antiqua sugar works and took to the slave trade early. He divided his time between his Newport town and Portsmouth country residences. In 1727 he settled on his father’s estate at Portsmouth, known as Redwood farm, which came into his possession on the death of his elder brother. By 1745 the estate was some 140 acres in size. Some of that land was from the Coggeshall land grant and may have been purchased from his wife’s family. The Redwood estate in Portsmouth was particularly known for its gardens. The Redwoods were a merchant family and they brought plants from their travels. He took great pride in his gardens and they were considered one of the most beautiful botanical gardens in North America. There were plants and trees imported from all over the world.

These are a few descriptions from the National Gallery of Arts work on “hot houses.” 1

Redwood, Abraham, Jr., c. 1760, in a letter to his plantation manager, describing Redwood Farm:

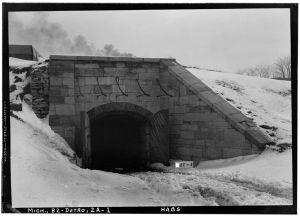

“I would desire you send to me one hhd (might be hogshead about 63 gallons) of good rum and one hhd of good sugar and I desire that you speak to your overseer to put up in Durt one dozen of Small orange Trees that has bore one or two years with the young fruit upon them, if to be had that has bore two or three years of Saffadella trees, four young figg trees and some Guavas roots, to put in my greenhouse, for I have made a garden of 1 1/2 acres of land and I have built a green house twenty-two feet long, Twelve feet wide and Twelve feet high, and a hotte house Sixteen feet long Twelve feet wide and Twelve feet high, and I have growing in my greenhouse Fifty young fruit trees from six inches to four feet high, and my Gardner says ye largest will not bear fruit these two years, and I have hotte house Strawberries, Bush beans and Crownations in Blossom.”

Redwood describes a greenhouse 22 feet long, 12 feet wide and 12 feet high.

Drowne, Samuel, June 24, 1767, describing Redwood Farm:

“Mr. Redwood’s garden. . . is one of the finest gardens I ever saw in my life. In it grows all sorts of West Indian fruits, viz: Oranges, Lemons, Limes, Pineapples, and Tamarinds and other sorts. It has also West Indian flowers—very pretty ones—and a fine summer house. It was told by my father that the man that took care of the garden had above 100 dollars per annum. It had Hot Houses where things that are tender are put for the winter, and hot beds for the West India Fruit. I saw one or two of these gardens in coming from the beach.”

Tropical West Indian fruits were grown in Rhode Island with the help of a hot house. It was well known that the Redwoods paid their garden manager very well

What happened to the Redwood Farm?

The Redwood Farm estate stayed in the family until 1882. In her book “This Was My Newport,” Maud Howe Elliott (daughter of Julia Ward Howe) describes the garden when she was a child in the 1850s and 60s.

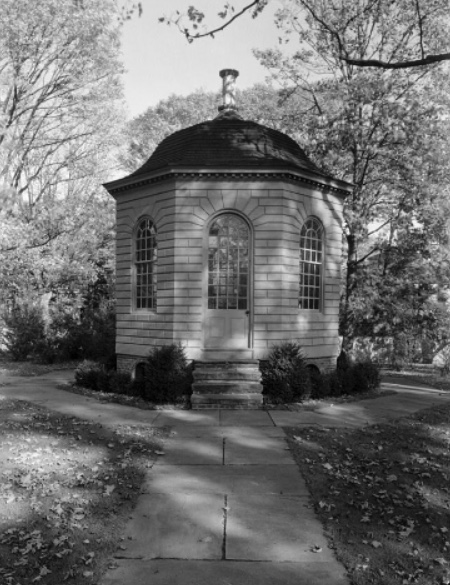

“The garden at “Redwood” was a marvel of taste and neatness. The high bush blackberries that topped the wall were known to every child within a radius of miles. At the corners of the long beds were enormous clumps of peonies. Flowers, fruit and vegetables amicably shared the sunny garden — a pair of acres in size — gooseberry and currant bushes forming the borders, while pear trees were planted at intervals in the center of the beds. There was a little garden-house where Miss Rosalie, the youngest daughter, held a Sunday school for children of the neighboring farmers. I have had cause all my life to bless Miss Rosalie for her gentle ministrations. The seeds of culture and breeding she sowed in the minds of her boys and girls have borne fruit and sweetened the life of generations.” 4

You can still see the “little garden-house.” It was moved to the grounds of the Redwood Library in 1917. It was originally designed by famed architect Peter Harrison for the Redwoods in 1766.

The Redwood home on West Main Road was allowed to deteriorate, but we do have an image of it from 1934. (5) According to British diarist Frederick Mackenzie, the home was used as a headquarters for soldiers during the British Occupation of Aquidneck Island.

Resources:

- National Gallery of Art: https://heald.nga.gov/mediawiki/index.php/Hothouse

- https://americangardenhistory.blogspot.com/2018/12/the-greenhouse-conservatory-in-early.html. About Early Hot Houses.

- https://stories.usatodaynetwork.com/slaveryinrhodeisland/abraham-redwood-antigua-and-the-west-indies-trade/ Redwood in the Slave Trade.

- Elliott, Maud Howe. This Was My Newport. Mythology Company, A. M. Jones, 1944.

- From the collection of the Providence Public Library.

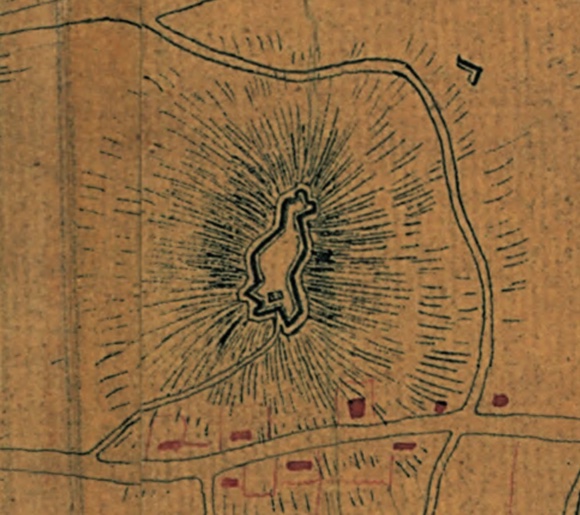

- Berthier Map from John Robertson’s book “Revolutionary War Defenses in Rhode Island.”2022, Rhode Island Publications Society.

- Garden House Image from Library of Congress.