Cora Mitchel as a suffragette

When we think of Portsmouth and the Civil War, we usually focus on Lovell Hospital or the local men that went to war. I’m beginning to discover that a prominent Bristol Ferry family, the Mitchels, had a unique history of escapes from the Confederacy. I had come across a newspaper article about Portsmouth resident Colby Mitchel and his daring escape from being kidnapped from school and impressed into the Confederate Army. ( I wrote an earlier blog about this story.) With further research I came across a first hand account by his sister, Cora Mitchel, of how the rest of the family escaped from Florida and traveled to their summer home in Portsmouth, Rhode Island. Cora related her story in a book in 1916 – Reminiscences of the Civil War. It was published in Providence by Snow and Farnham and it is available digitally online. The information in this blog came from Cora’s book.

Why was the Mitchell family down South when the Civil War began?

The father of the family, Thomas Leeds Mitchel of Groton Connecticut, was a cotton merchant in Apalachicola, Florida. Cotton was shipped down river to be compressed and taken down to the bay where steamers and sailing vessels would carry it to England and New England. There were a number of Northerners in the community as well as families from the South. Mitchel did not believe in slavery. He employed blacks, but he did unwillingly own three. These three had come to him and asked him buy them. Otherwise they would be sold on the open market. Cora remembers them as faithful, valuable servants who were like family members.

Cora’s mother was Sophia Brownell of Providence. The Brownell family was one of the earliest families in Portsmouth. The Mitchels had their summer residence in Portsmouth in the area where the first Brownells held their land. It was not uncommon for Southern planters to spend their summers in the milder climate of Aquidneck Island.

What happened to the family when the Civil War began?

Cora remembers the excitement when war seemed imminent. Her father was convinced that the war could not be long and that peace would be restored. He had large properties in the South as well as his business, so he decided not to go North. Everything he had would be confiscated if he did.

After Ft. Sumter, the town began to prepare for war. Defensive companies formed and drilled. Sandbags armed with canon lined the bay and the town was considered to be in jeopardy. In the Spring of 1861, Cora’s sister, Floride, was to be married. Mother Sophia was allowed through lines and she went north for daughter’s trousseau!

A blockade shut up the port. Business was at a standstill. Cora’s sister and brother-in-law went to Columbus, Georgia. Fifteen year old Cora was sent to stay with her sister and go to school in Columbus.

Young Colby Mitchel sixteen or seventeen years old at the time) was taken from the schoolhouse in Apalachicola by a detachment of soldiers and conscripted into the Southern army. How his father rescues him and brings him North is another interesting story.

The family was beginning to realize the gravity of the whole situation they were in. Neighbors began to resent Colby’s desertion. Mother Sophia was left with four small children and almost no food or money. Son Thomas was around ten, Sophia was about six, Louis was four and Gaston was about three.

Mrs. Mitchel’s Dangerous Journey to get Cora

Mother Sophia did not want to leave Cora behind. Columbus, Georgia was three hundred miles away and Sophia left her younger children with their Aunt Ann, their nurse. She set off on a perilous journey to get her daughter. The Confederates had obstructed the river with fallen trees, debris, etc. Sophia had to get around it. She rowed against the current as far as the obstruction. She was able to get a boat for the rest of the journey, but she was exhausted when she arrived at Columbus.

When they traveled down river to get back to Apalachicola, they needed to get a passport to get through the Confederate lines. At first the soldiers Sophia approached wouldn’t give it to her. Cora tried approaching a young soldier and he helped them even though he had orders not to let them pass through. A boatman who was originally from Italy was waiting for them at the obstruction. They found a route through a bayou to get around the obstruction. They had the necessary passport to get through the guard posts and the Confederates let the women and their boatmen pass. Their little boat was leaking badly as they reached a deserted wharf at Apalachicola.

Times were tough in Apalachicola. The town was built on a sand bar and could not grow food on its own. No food shipments were coming. There were no cattle or poultry. What rice they had had spoiled. Everyone lived on corn meal. The situation was getting worse, but Sophia was waiting until Spring to get the transport ship to go North. It was a dangerous time. The men who had helped their father and Colby escape had been shot by a company of soldiers.

The Journey North

The Captain of a Union ship said he was given orders not to accept refugees, but mother Sophia persisted. They waited for the transport ship on the Somerset – an old ferryboat. The crew was good to the family. The ship’s tailor even made clothes for the boys. The crew missed their own families so they enjoyed the Mitchel children. The Captain even insisted on giving Sophia $500 for trip (their confederate money wouldn’t do them any good getting up north). The family transferred to the transport ship, Honduras. They stopped at Tampa and Cedar Keys before they landed at Key West. Key West was crowded with refugees and blacks that were trying to escape from the South. Yellow fever was spreading throughout the town. Ten days later a steamer came from New Orleans. The Captain told Sophia there was no room, but Sophia pleaded. The Captain reluctantly allowed them to stay in a room that flooded each morning. Seasick and uncomfortable throughout the trip, the family arrived home to Rhode Island. They were reunited with Colby and father Thomas.

Many of the Mitchel family continued to spend time in the Bristol Ferry neighborhood. On his eighty-ninth birthday, Colby received the Boston Cane as the oldest resident of Portsmouth. Cora Mitchel was one of the founders of the Newport Women’s Suffrage Association and served as President and Vice President of the Association. Sophia was a noted artist and had a studio at Bristol Ferry. Floride made her way to Rhode Island as well. The “Mitchel Sisters” were a force in the Portsmouth community in both the arts and social reforms.

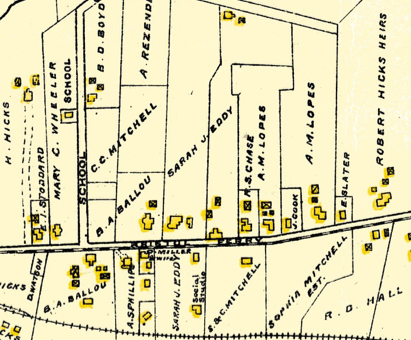

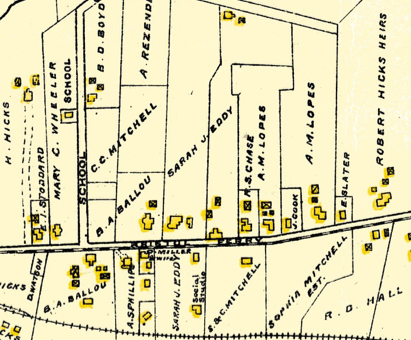

Note Mitchel family land on 1907 Portsmouth map.