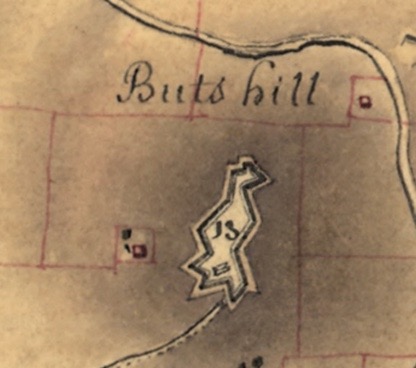

We know about the Black Regiment’s presence at Butts Hill Fort in 1780, but a letter from Camp Butts Hill in August of that year makes us aware of another black soldier in camp – Phelix Cuff. Whether Cuff was free or a slave is up for debate. Cuff enlisted on August 7, 1780 as a private in Captain Zaccheus Wright’s Company. By that time in the War for Independence, there was a lack of able-bodied white men and it became acceptable to accept black slaves and free blacks into the Massachusetts militia. Just a few days after Cuff enlisted, a Waltham resident named Edward Gearfield claimed that he owned Cuff.

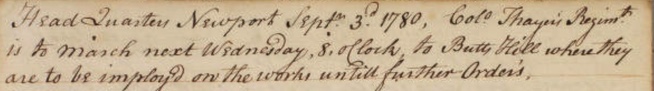

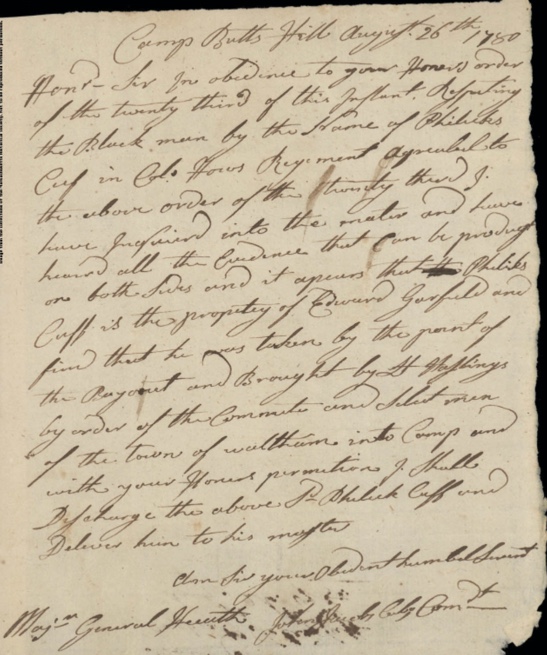

In letter dated August 26th, 1780 from Camp Butts Hill, Colonel John Jacobs writes to Major General Heath:

“In obedience to your Honor’s order of the twenty-third of this instant, respecting the Black man by the Name of Philicks Cuf in Col. Hows Regiment Agreable to the above order of the twenty third I have Inquired into the mater and have heard all the evidence that Can be produced on both Sides and it appears that Philiks Cuff is the property of Edward Garfield and find that he was taken by point of the Bayonet and Brought by Lt. Hastings by order of the Commitee and Select men of the town of waltham into Camp and with your Honors permission I shall discharge the above Sd. Philicks Cuff and Deliver him to his master.” *

What is the story? Another letter, this one from Abraham Peirce and others from Waltham, Massachusetts, was dated August 17th, 1780. The men express their “duty to inform your Honor the Truth of Phelix Cuff being engaged for this town in the Militia for three Months…” The men write that had ‘Your Honor” (Heath) been rightly informed he would not have permitted Edward Gearfield to take Phlix Cuff and his arms and Accoutrements. They refute the idea that Phelix was “clandestinely” taken. Edward Gearfield was at home when Phelix signed up for the militia. From 1778 Massachusetts did have all black regiments, but Cuff was part of an integrated regiment. Slaves might expect that they would receive freedom for their service. The Waltham men wrote: “we are persuaded that he (Gearfield) has no Demand on Justice on the said Phelix as a Slave whatever he may pretend by any pretended Bill of Sale.” **

In the letter the Waltham men pointed out that Cuff’s arms belonged to the town and his uniform was purchased by Cuff with the money Cuff received from the town when he enlisted. Gearfield has refused to give back the Arms and uniform. Cuff “is desirous of returning with Lieut. Hastings.” When Cuff was discharged he had served just twenty-four days.

Cuff would not return to Gearfield and with three other “slaves” he went into hiding. Hastings learned where Cuff was hiding and gathered a small group to capture him, but he didn’t succeed. Cuff filed charges against Hasting and his men accusing them of “incitement to riot.” In September of 1781 Hasting requested that Waltham pay the expenses of his defense but the selectmen denied the request. Cuff went on to collect wages for his service in the war. Massachusetts paid Cuff “1,500 pounds in currency and 60 bushels of corn” for his service” ***

References:

*Letter from John Jacobs to William Heath regarding the status of Phelix Cuff, 26, August 1970. https://www.masshist.org/database/704?mode=transcript

** Letter from Abraham Peirce regarding Phelix Cuff’s service in the militia. http://www.masshist.org/database/viewer.php?item_id=703&img_step=1&mode=dualLetter from John Jacobs to William Heath regarding the status of Phelix Cuff, 26 August 1780. https://www.masshist.org/database/704

Massachusetts, U.S., Soldiers and Sailors in the Revolutionary War

Massachusetts Society Sons of the American Revolution: African American Men in the Revolution (massar.org)

***. Kenneth W. Porter, “Three Fighters for Freedom, Maroons in Massachusetts: Felix Cuff and His Friends, 1780.” The Journal of Negro History, 28:1 (January 1943), 51. This reference was listed in the Mass. Society Sons of the American Revolution blog. I was not able to find the original article.

Slave and soldier, he fought for freedom on two fronts: Stephanie Siek http://archive.boston.com/news/local/massachusetts/articles/2008/04/20/slave_and_soldier_he_fought_for_freedom_on_two_fronts/