As I was attending the Annual Commemoration Service of the 1st Rhode Island Regiment, I noticed the insignia on buttons some of the guests were wearing. That insignia is also carved in stone on one of the early monuments at Patriots Park. I am gathering materials for a lesson plan on the Black Regiment, and I would like to have students work with the correct flag. I often see two similar flag designs depicted with images of the Black Regiment. It is certainly possible that they would have fought under different flags. In February of 1781 the 1st and 2nd Regiments were combined into the Rhode Island Regiment. The insignia at Patriots Park resembles one of the flags and it is logical that the monument designers would want to reflect the flag used by the 1st Rhode Island Regiment while they were a separate unit.

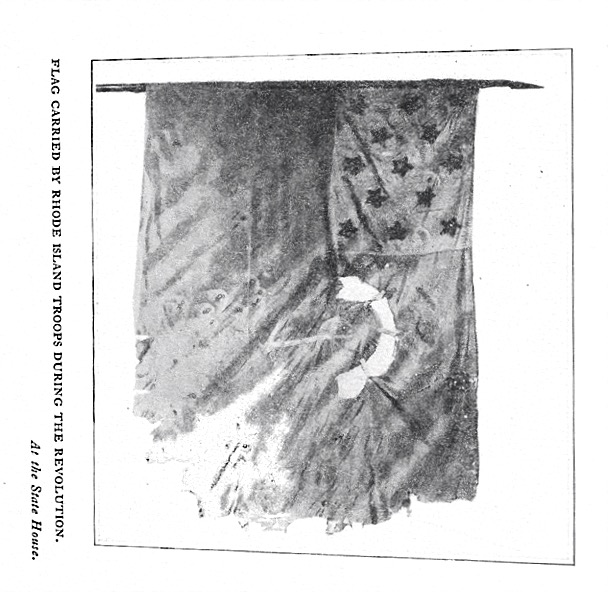

An online search was confusing, but I remembered a 1930 book on Rhode Island flags and symbols by Howard Chapin. There was a depiction of the regimental flag of the 1st Rhode Island Regiment that is kept at the State House. It is described as:

“The field was white, charged with a blue scroll being the inscription “R. Island Regt.” In the upper corner there is a blue canton charged with thirteen white stars.”

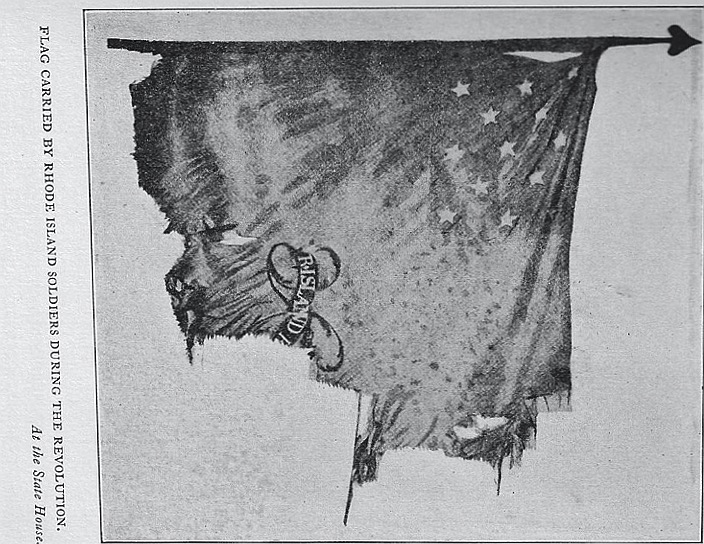

The Regimental flag of the 2nd Rhode Island Regiment is pictured as well. This flag is also listed as being at the State House. The description reads:

“The Second Rhode Island Regiment carried a somewhat similar flag, having a white field, charged with a blue foul anchor and the motto, “HOPE,” and having in the corner a blue canton charged with thirteen gold stars…After the passage of the regulation of February 23, 1780, the flag bearing the blue anchor doubtless qualified in a sense partially as a State flag.”

The anchor design is an ancient emblem in Rhode Island. Rhode Island was a seafaring colony. The seal of the colony drawn by William Dyer in 1647 has an anchor. The “foul anchor” described is the robes entwined in the anchor. One description notes that the white is the color of their uniforms and a symbol of the commonwealth. The 13 stars reflect the colonies and may be a reflection of the seals of Portsmouth and Providence.

In May of 1664, the General Assembly “Ordered, That the Seal, with the mottoe Rhod Iland and providence plantations, with the work Hope over the head of the Anker, is the present Seale of the Colony.”

Resources:

Chapin, Howard. Illustrations of the Seals, Arms and Flags of Rhode Island. Providence, RI, Rhode Island Historical Society, 1930.