After the Battle of Rhode Island, John Sullivan had to explain his retreat from Aquidneck Island. We have a record of that explanation in a letter published in the Providence Gazette on September 26, 1778. “Letter from the Hon. Major General Sullivan to the President of Congress dated headquarters Tiverton, August 31, 1778″. I was able to find that article and transcribe it. This is quite a lengthy letter, so In the next few blogs I will take you through Sullivan’s explanations in stages. In reading through this letter, we need to remember that Sullivan had been part of retreats before and the Congress had questioned his actions. I am not a military historian and I am only now beginning to study the Battle of Rhode Island, but this is a primary source to be respected as a first hand account of the man in charge of the American troops in the battle.

For some background I searched for some basic information about John Sullivan. He was born in New Hampshire in 1740, the son of Irish immigrants. His original training was as a lawyer.

In 1772 New Hampshire’s Royal governor appointed him as major in the New Hampshire militia. As the break with Britain was unfolding, he began to favor the rebel cause. Sullivan was sent as a delegate to the First Continental Congress in 1774. In 1775 Sullivan was sent to the Second Continental Congress. Congress appointed George Washington Commander in Chief and John Sullivan as brigadier general. Sullivan joined the army at the siege of Boston. Later he took command of a force in Quebec in a failed invasion. Sullivan had to withdraw the survivors. He was captured in defeat at the Battle of Long Island. British General Howe released him on parole to deliver a message to Congress. He was later released in a prisoner exchange for captured British general Prescott. He had some success in battle but had continued difficulties as well. In Early 1778 he was transferred to the post of Rhode Island where he led the continental troops and militia. John Sullivan fought bravely, but his command decisions were questioned on a number of occasions. He had to defend himself, but he was often judged not at fault. Sullivan needs to explain his decisions.

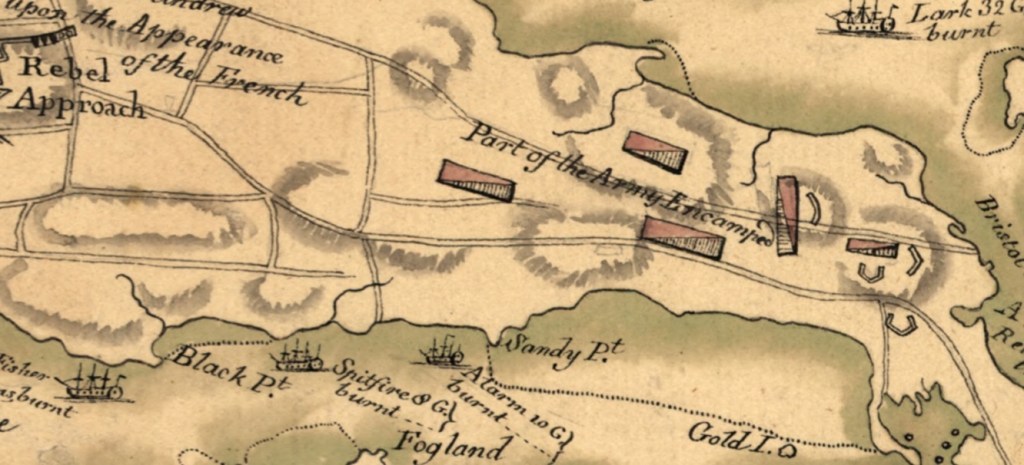

The first part of the letter deals with the prelude of the battle. The French fleet under Count De’Estaing had gone to Boston to make repairs and Sullivan expressed belief that they would come back soon. He decided to carry on with the planned invasion of Aquidneck Island.

“I thought it best to carry on my approaches with as much vigor as possible against Newport, that as time might be lost in making the attack upon the return of the fleet, or any part of it, to cooperate with us. I had sent expresses to the Count to hasten his return which I had no doubt would at least bring part of his fleet to us in a few days.”

Initially he had good success and the enemy abandoned positions. “…on the 27th we found they had removed their cannons on all the outworks except one.” He details the British positions at Newport and described them as two basic lines. He expresses regrets that he had not stormed some of these defenses when the cannons had been withdrawn, but he began to lose manpower. “

He writes he found: ” ..to my great surprise, that the volunteers which completed the great part of my army, had returned [left for home], and reduced my numbers to little more than that of the enemy; between two and three thousand returned in the course of twenty-four hours, and others were______ going off, upon a supposition that nothing could be done before the return of the French fleet.”

Sullivan’s troops were a combination of Continental soldiers and militia. Many militia units came from nearby Massachusetts and in discouragement that the mission could not be accomplished without the French fleet, many units headed home. General Sullivan was in a difficult position.

“Under these circumstances, and the apprehension of the arrival of an English fleet with a reinforcement to relieve the garrison, I sent away all the heavy articles that could be spared from the army to the main; also a large party was detached to get the works in repair on the north end of the island to throw up some additional ones, and put in good repair the batteries at Tiverton and Bristol, to receive a retreat in case of necessity.”

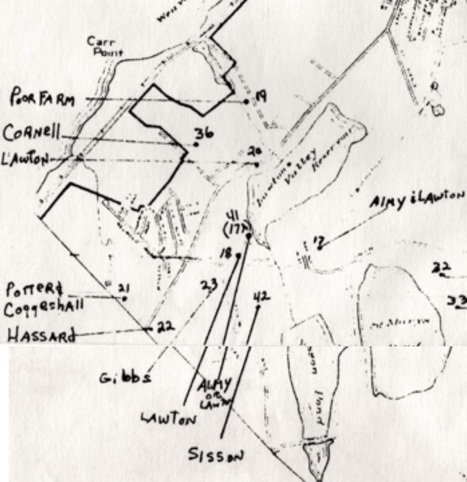

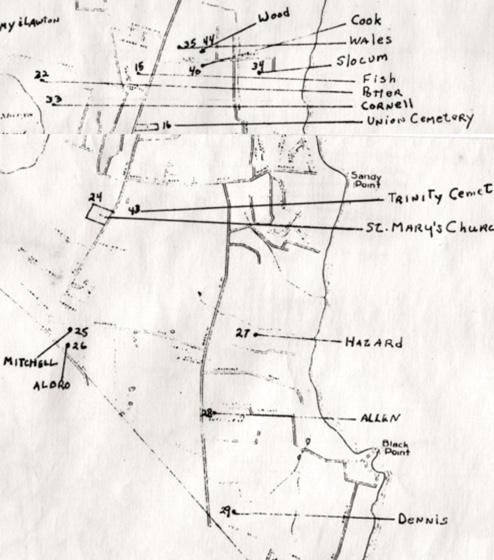

General Sullivan began to prepare for a retreat. He knew that enemy reinforcements were coming and his best course was to retreat. This was not a hasty retreat. He ordered increased defenses in the North (especially Butts Hill Fort and forts guarding the Bristol Ferry and the ferry to Tiverton). He wanted to get all his weaponry out so it would not fall into enemy hands to use against them another day. His letter makes clear that this was an “unanimous” decision to first retreat to Portsmouth and hope that the French would return.

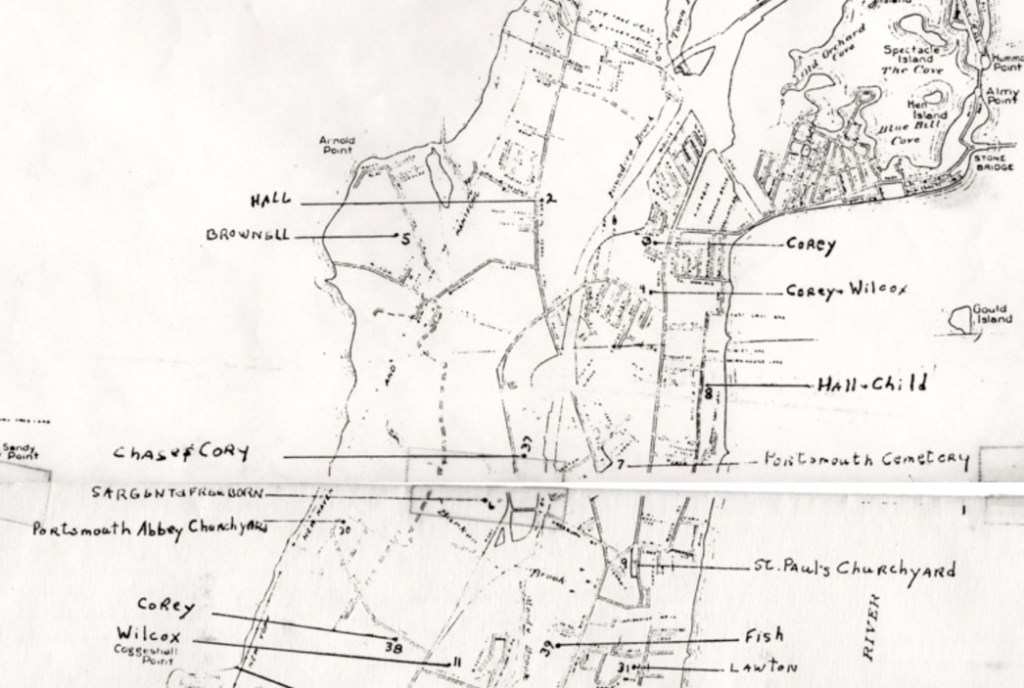

“On the 28th a council was called, in which it was unanimously decided to remove to the north end of the island, fortify our camp, ______ (secure?) our communication with the main, and hold our ground on the island til we could know whether the French fleet would _____ return to our alliance. On the evening of the 28th we moved with our stores and baggage, which had not been previously sent forward, and about two in the morning encamped on Butts’s Hill, with our right extending to the west road, and left to the east road; the flanking and covering parties ____further towards the west road on the right and left.”

Sullivan details the positions of his forces on the evening of August 28, 1778.

“One regiment was posted in a redoubt advanced to the right of the __ line. Colonel Henry B. Livingston with a light corp, consisting of Colonel Jackson’s detachment, and a detachment from the army was stationed in the east road: Another light corp, under command of Colonel Laurens, Col. Fleury, and Major Talbot, was posted on the west road. These corps were posted near three miles in front; in the rear of these was the picquet of the army, commanded by Col. Wade.”

The stage is set for battle.