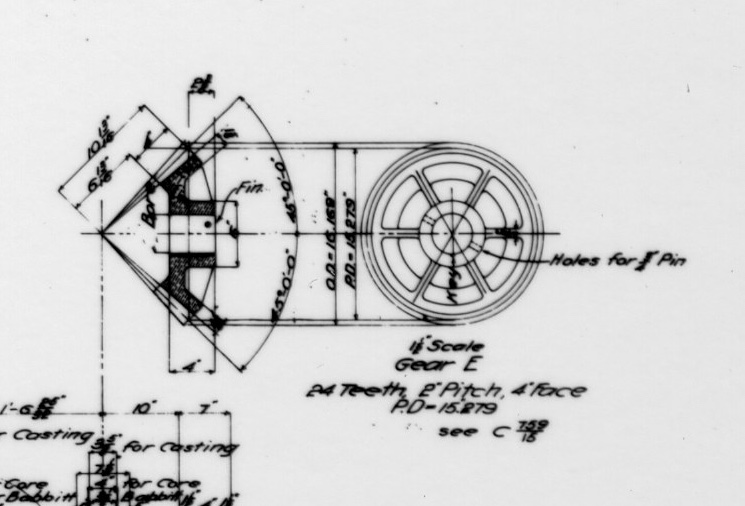

One of the unique items in our Old Town Hall exhibits is a gear that served to swing the draw bridge of the Sakonnet River Railroad Bridge. The gear was in service from 1899 when a new bridge was constructed to 1988 when a barge ran into the bridge. In 2006 the bridge swing structure was removed and the Portsmouth Historical Society was gifted with the gear.

The 1899 railroad bridge was built by the New York, New Haven and Hartford Railroad. The railway bridge served a number of railroad lines, including the Providence and Worcester Railroad and the Old Colony Railroad. The original bridge was built for the Newport and Fall River Railroad and was constructed by the Pennsylvania Steel Company in 1864. From 1889 to 1899 the New York and New Haven railroad was in a controversy with the Secretary of War. The bridge was considered a block to navigation of the Sakonnet River and the War Department wanted a 100 foot draw span to facilitate movement of boats through a particularly treacherous current area. As the new bridge was being built, the old bridge still served for transportation to the island. The bridge was considered such an important link between Aquidneck Island and the mainland that the Newport Artillery Company had the duty of guarding it during World War I.

The bridge served to bring supplies to Aquidneck Island even until the 1970s. Weyerhaeser, the Naval Base and Naval Supply Center argued that they needed the bridge for hundreds of carloads of supplies. The railway found the route unprofitable and they petitioned to stop the line. The bridge itself became irreparable when a barge hit it in 1988.