During the 1800s the Durfee Tea House was famous for its tea-cakes. But who was “Mrs Durfee” or was she “Miss Durfee?” Newspaper and magazine articles seem to conflict. In researching further, I found there were two Durfee women who ran the same Tea House but at different times.

During the 1800s the Durfee Tea House was famous for its tea-cakes. But who was “Mrs Durfee” or was she “Miss Durfee?” Newspaper and magazine articles seem to conflict. In researching further, I found there were two Durfee women who ran the same Tea House but at different times.

Mrs. Mary G. Durfee

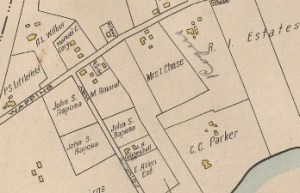

Samuel Clark, who took over the Cundall Mills property in the Glen, sold the original lot without a house to Mrs. Mary G. Durfee. in 1836. The house must have been built shortly after the sale. Mary Durfee must have originated the tea house because when the property was sold to Ruth Durfee in 1857 it was already known as “Mrs. Durfee’s Tea House.” In the days of Mary Durfee the Tea House was a cultural center for Portsmouth. Many activities were held there including the original Sunday School for the Union Meetinghouse which was organized by social reformer Dorothea Dix.

When an article mentions “Mrs. Durfee” and the time period is before 1857, we know that it is referring to Mary G. Durfee. A 1853 book by John Dix, (Handbook of Newport Rhode Island) refers to “Mrs. Durfee’s” fame.

Are you fatigued, reader, with your ramble? if so, near the Glen, and between it and the main road, are the snug quarters of a lady who cheerfully dispenses the cup which cheers but not inebriates to all those who require soothing souchong, or glorious green, or magnificent mixed tea. Capital coffee too, may here be found, and choicest cakes, (we are growing alliterative.) What can be pleasanter after a ramble through that charming glen, than a quiet gossip over the incomparable infusion of the Chinese leaf? The very idea of it inspires us, and so we close the chapter by saying or singing :—a la Mary Wortley Montague:

And then, when our lovely Glen Ramble is past,

And wo rest our tired limbs on a sofa at last,

How delightful to mark on the table outspread

The primrose-hued butter, the delicate bread!

The cakes and the cream, the preserves and the ham,

The eggs, the hung beef, the sliced peaches and jam,

The coffee so fragrant, the fine flavored tea,

And the other good things of good Mrs. Durfee!

Reader, Mrs. Durfee is no fiction of our imagination; she keeps the Tea-House of The Glen!

A Newport Mercury article from Oct. 14, 1893 recounts trips forty years before to the tea house. At that time Mrs. Mary Durfee was the proprietor of the tea house.

“On coming back from the Glen, it is usual to take tea at Mrs. Durfee’s celebrated tea-house close by, an Inn as charming as the Royal Sandrook of the Isle of Wight, and then reach Newport at the twilight hour. Mrs. Durfee’s griddle cakes were famed over all Rhode Island and the ____ appetites of the young ladies, after the drive and the courting in the Glen, proved their excellence, as well as the fact that women cannot live by romance alone. The grounds about the Inn were very pretty and a number of persons boarding there through the summer. In addition to these regular lodgers, Mrs. Durfee turned many an honest shilling by the delicious teas she furnished to excursion parties.”

Miss Ruth S. Durfee

The second proprietor, Ruth S. Durfee , was known as a well educated woman who in her younger days ran a school in her home. She is listed in the household of Mary G. Durfee and may have been related to her. I haven’t tracked down a good genealogy to confirm this.

A 1893 Harper’s Monthly Magazine called Miss Durfee the “Goddess of the Glen.” No trip out to the romanic Glen was complete without stopping at the Durfee house for refreshments. Many of the Newport society greats would host dinners and events at the Durfee Tea House. One guest describes a visit in the 1870 timeframe: “Miss Durfee, very lame but most hospitable, received her guests and soon the famous tea-house cakes were served.” Ruth’s obituary in the Newport Mercury, Jan 9, 1892, tells us she was “helpless so far as walking was concerned, and, and she was obliged to propel herself about the house in a wheeled chair.”

The Durfee Teahouse and the its barn have been moved to Glen Road. The original location is part of Rhode Island Nursery property today. It was closer to the Glen itself and served as an entry or exit point to a day in the Glen.

Recipe

And what was the recipe for the tea cakes?

“These were meal cakes, made as thin as a wafer, slightly sweetened with a suspicion of nutmeg flavor. Baked on a griddle that covered the whole top of the stove, they were compounded of a milk mixture consisting of ten eggs to a quart of milk, the finest Rhode Island meal, butter, sugar and spice….After supper, the frolic terminated in a Virginia Reel, in which all, young or old took part, and then the revelers returned home by the light of the moon.” (Newport Historical Society Bulletin, April 1926).

No matter which Durfee Tea House proprietor is mentioned, it is clear that the food was marvelous and the mistress of the tea house was a master of hospitality. We raise a cheer for Mary G. Durfee the founder of the tea house and a cheer for Ruth S. Durfeee, the “Goddess of the Glen.”