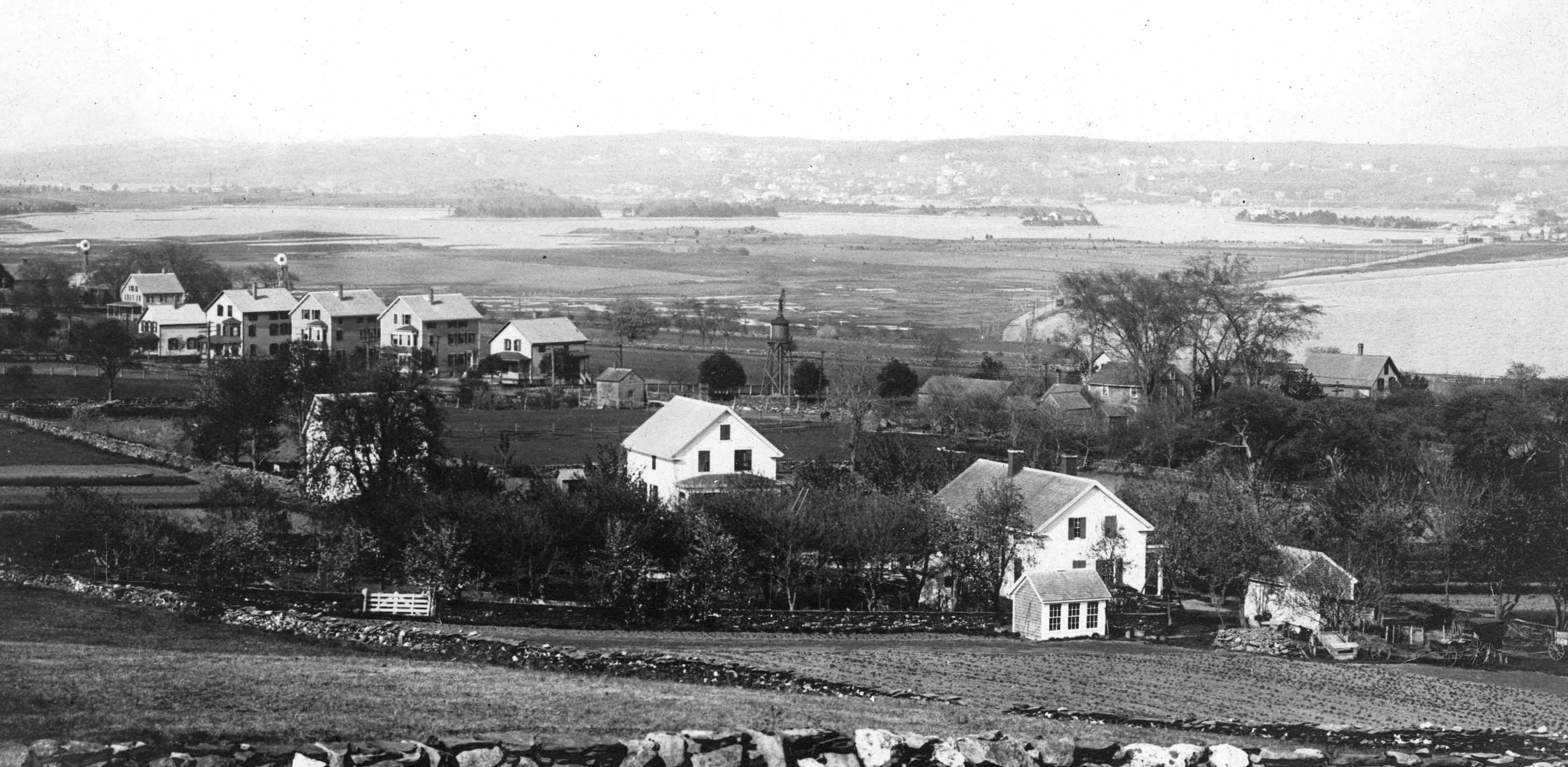

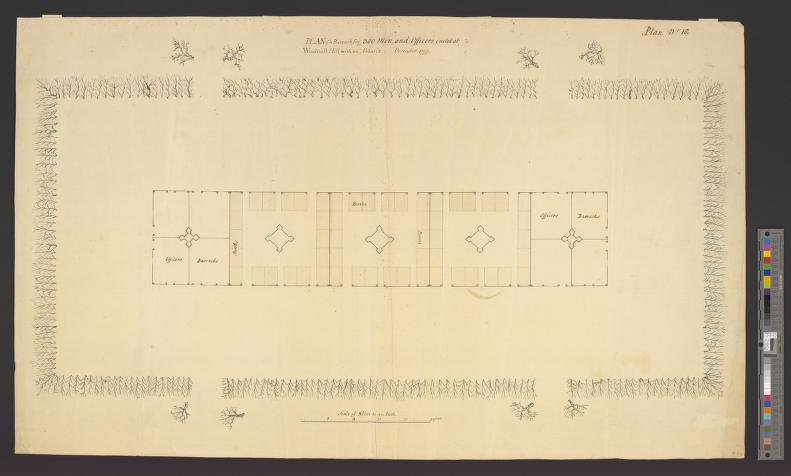

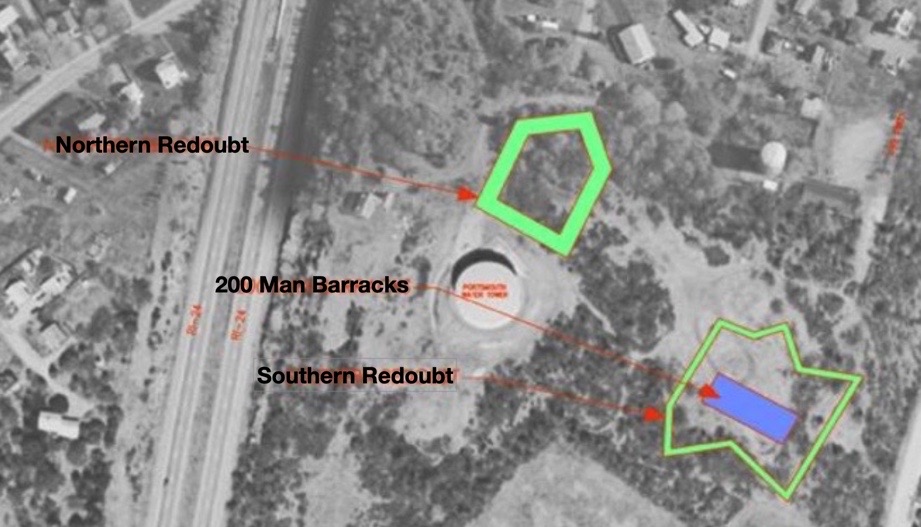

Part 4 in brainstorming a tour of Butts Hill Fort: Focus on the Battle of Rhode Island. At the SW corner of the Fort.

We pick up our timeline:

August 28th: (From Sullivan’s letter to Congress after the battle):

Sullivan details the positions of his forces on the evening of August 28, 1778.

“One regiment was posted in a redoubt advanced to the right of the __ line. Colonel Henry B. Livingston with a light corp, consisting of Colonel Jackson’s detachment, and a detachment from the army was stationed in the east road: Another light corp, under command of Colonel Laurens, Col. Fleury, and Major Talbot, was posted on the west road. These corps were posted near three miles in front; in the rear of these was the picquet of the army, commanded by Col. Wade.”

“On the evening of the 28th we moved with our stores and baggage, which had not been previously sent forward, and about two in the morning encamped on Butts’s Hill, with our right extending to the west road, and left to the east road; the flanking and covering parties ____further towards the west road on the right and left.”

August 29th, 1778: What was going on around Portsmouth during the day of the battle? These engagements are detailed for us by Seth Chiaro. They are culled from The Rhode Island Campaign written by Christian McBurney.

West Main Rd and Union Street Engagement: During the early hours on August 29th around 7:00 AM, Hessian Chasseurs made contact with American forces near the intersection of West Main Rd and Union Street. A small engagement took place from that area and would eventually lead towards the Lawton Valley. The Hessians would eventually break the American line with Artillery.

East Main Rd and Union Street Engagement: By 8:00 AM the British 54th, 22nd, 43rd, and the 38th Regiments of Foot are ambushed by Col. Nathaniel Wade’s American picket line. The Americans fired two volleys into the British column. The picket line retreated towards Quaker Hill. The 43rd RoF took pursuit down Middle Road while the 54th, 38th, and 43rd RoF continued down East Main Rd.

Turkey Hill Engagement: German Captain Von Malburg pursued Col. Laurens Regiment to Turkey Hill. Laurens men took up a strong defensive position on top of Turkey Hill. Col. Laurens sent a request for reinforcements to General Sullivan. Sullivan responded with orders to ‘”fall back to the main line.” General Sullivan sent Webb’s Connecticut Regiment to support Laurens’ retreat. Ameican and Hessian units engaged on Turkey Hill before the Americans fell back. Laurens’ Regiments fell back to General Nathanael Green’s position to the right of Butts Hill. By 8:30 AM the Hessians had secured Turkey Hill.

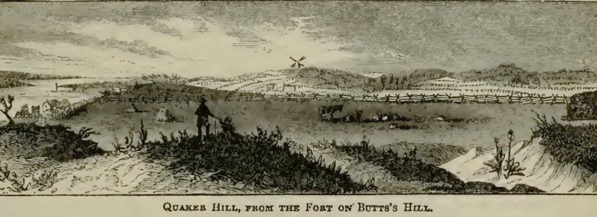

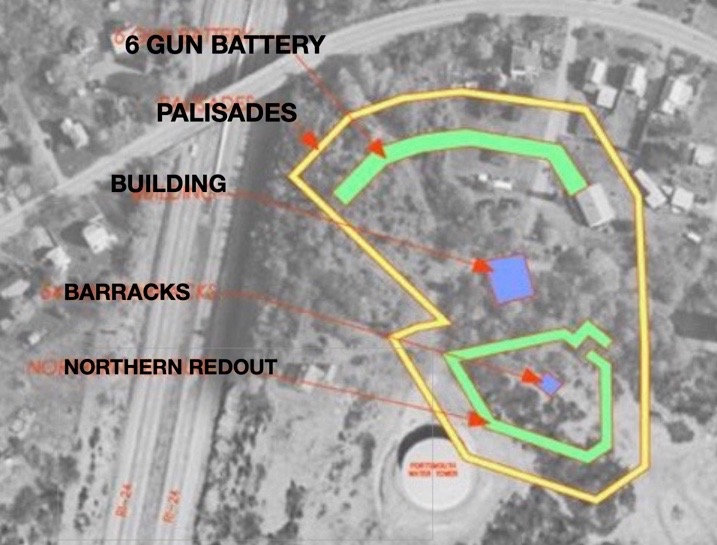

Quaker Hill Engagement: The British units that had engaged with American Forces were now engaged on Quaker Hill. The British forces formed a line that extended from East Main Rd to about where Sea Meadow Drive is located. Americans were also formed between the Quaker Meeting House and Hedly St. General Sullivan sent reinforcements to Quaker Hill, giving the Americans the upper hand, but only for a short time. Both sides engaged on the hillside over a poorly defended artillery position. American forces were able to secure the position. The British attacked and poured effective volleys of musket balls into the Americans causing them to retreat. Sullivan ordered the units fighting on Quaker Hill to retreat back to the mainline around Butts Hill Fort. The engagement on Quaker Hill lasted a full hour. The British attempted to attack Butts Hill Fort but the 18 pound cannons from Butts Hill Fort kept the British from advancing.

Lehigh Hill Engagement (Durfee’s Hill): General Nathanael Greene held the right flank of the American Army, along the right-wing stood a small artillery redoubt. This was a vital position for both sides. The 1st RI Regiment (Black Regiment) was under the direct command of Major Samiel Ward who was commanded by Col. Christopher Greene, a distant cousin of Nathanael Greene. German Captain Malsburg was ordered to attack the hardened position. The first attack failed. The 1st RI Regiment held its ground. The Hessians tried multiple times to take the position. The Hessians tried to flank the position, this also failed. On the third attempt, the 2nd RI Regiment supported the 1st RI Regiment. As the 2nd RI Reg. approached the redoubt the Hessians were attempting to climb the walls. All together Greene had about 1,600 soldiers fighting on the Lehigh Hill. Units included 1st RI Regiment, 2nd RI Regiment, Livingston’s 1st Canadian, Sherburne’s, and Webbs Regiments. More than 800 Continentals including Laurens advance guard and Jacksons’ Detachment participated. The American line veered SW at a 45-degree angle from Butts Hill to Durfee’s Hill making the American fire even more effective. Col. Henry Jackson’s men fixed bayonets and charged into the Hessian Line, turning the tide of the battle. The Battle was over at 4 pm. The Hessians retreated to Turkey Hill. Both sides exchanged cannon fire throughout the night. Cannon fire was also exchanged between Turkey Hill and the Butts Hill Fort.

August 30, 1778

From Sullivan’s letter: “The morning of the 30th I received a letter from his Excellency General Washington, giving me notice that Lord Howe had again sailed with the fleet, and receiving intelligence at the same time that a fleet was off Block Island and also a letter from Boston, informing me that the Count D’Estaing could not come round so soon as I expected, a council was called, and as we could have no prospect of operating against Newport with success, without the attendance of a fleet, it was unanimously agreed to quit the island until the return of the French squadron.”

The retreat plan in Sullivan’s words:

“To make a retreat in the face of an enemy, equal, if not superior in number, and cross a river without loss, I knew was an arduous task, and seldom accomplished, if attempted. As our sentries were within 200 yards of other, I knew it would require the greatest care and attention. To cover my design from the enemy, I ordered a number of tents to be brought forward and pitched in sight of the enemy, and almost the whole army employed themselves in fortifying the camp. The heavy baggage and stores were falling back and crossing through the day; at dark, the tents were struck, the light baggage and troops passed dawn, and before twelve o’clock the main army had crossed with the stores and baggage.

Resources:

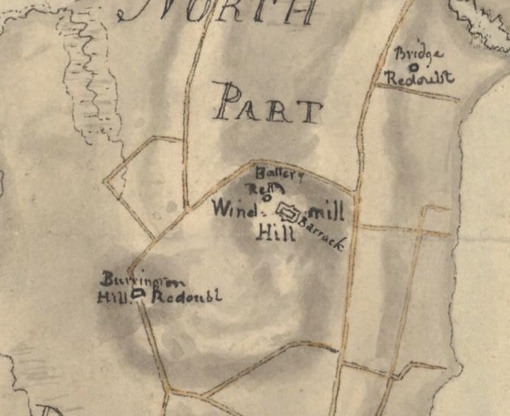

Plan of the Battle of Rhode Island from a Commonwealth Land Title Insurance Company map, 1926

Sullivan’s letter to the Continental Congress which was published in the Providence Gazette, September 26, 1778.