Last year when we featured Ruth Earle as a Portsmouth woman of note , we highlighted her involvement in the Girl Scouts among her achievements. This year we introduce Gertrude Macomber Hammond – the woman who was Ruth’s Girl Scout Leader and a founder of the scouts in Portsmouth. There are so many interweaving of our Portsmouth women that it is not unusual for us to find them in each other’s stories.

Gertrude Macomber was leading the “Bluebird” Girl Scout troop in Portsmouth in 1921. She wasn’t alone in this effort. Fifteen women met in 1922 to form a troop committee to aid the Portsmouth scouting movement. They lent their support to provide money and assistance to Gertrude and the thirty-five girls who regularly attended the weekly meetings.

In a 1923 Newport Mercury article we find ladies formally calling themselves “The Portsmouth Girl Scout Aides.” These women were meeting to support the efforts of a Girl Scout troop in Portsmouth and “Captain” Gertrude Macomber gave a talk on her recent camp and convention experiences in Washington. Mrs. John Eldredge, a school superintendent and director of the Social Studio, was there to serve tea.

Under the auspices of “Captain” Gertrude Macomber, newspaper accounts show the Girl Scouts engaging in some creative activities. A Girl Scout Circus was held in 1925. Miss Mary Chase acted as ringmaster. There was a chariot race between two girls in kiddie cars and Marjorie Hall did a tight rope act with the rope stretched over the floor. The girls played homemade musical instruments made from curtain rods, funnels and frying pans. There was a parade with animals like monkeys and ducks – perhaps girls in costumes?

By 1926 the Girl Scouts had grown large enough to have two patrols in the troop. The “Monkey Patrol” had a camp at Gertrude’s home to work toward a cook badge. Gladys Gibson made a meatloaf, Hope Manchester made a fruit salad, baking powder biscuits were created by Margaret Martin and a mystery cake was make by Ruth Peckham.

That same year Gertrude opened “The Quaker Hill Tea Room and Craft Shop” in her home. She added a “glassed-in piazza” to the north side of her house so that her customers would have “a wonderful view of the Seaconnet River to the Stone Bridge and the northwest part of the Island and Narragansett Bay.” – according to a 9/11/26 Mercury article.

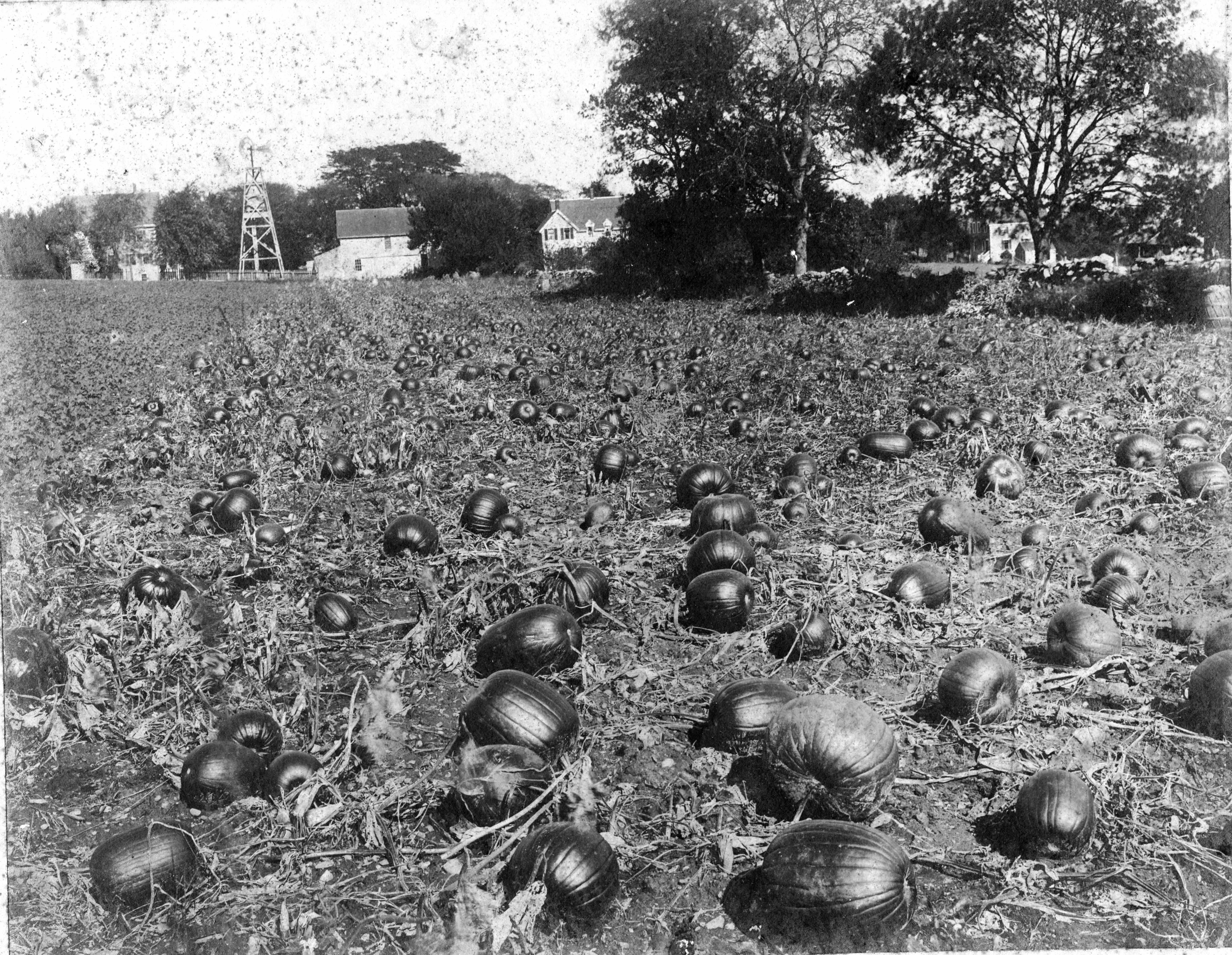

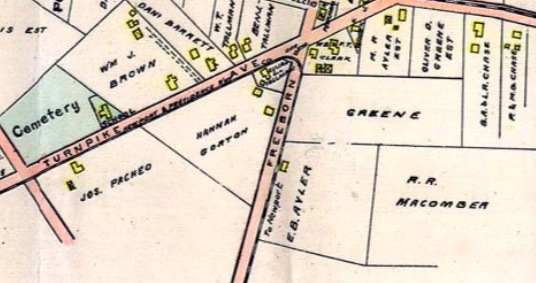

Gertrude was the daughter of Isaac Macomber and the grand-daughter of Joseph Macomber who brought the Aylers and other families to Portsmouth. In 1931 Gertrude became the bride of Noel Hammond who leased and farmed her father’s land. She continued with her Tea House and lived a long life in Portsmouth

____________________________________________________________________________

How many of these 13 requirements for a “Cook Badge” could you master today?

Girl Scout Cook badge, 1918-1927

- Build and regulate a fire in a coal or wood stove, or if a gas range is used know how to regulate the heat in the oven, broiler and top.

- What does it mean to boil a food? To broil? To bake?

- Why is it not advisable to fry food?

- How many cupfuls make a quart? How many tablespoonfuls to a cup? Teaspoonfuls to a tablespoon?

- Be able to cook two kinds of cereal.

- Be able to make tea, coffee and cocoa properly.

- Be able to cook a dried and a fresh fruit.

- Be able to cook three common vegetables in two ways.

- Be able to prepare two kinds of salad. How are salads kept crisp?

- Know the difference in food value between whole milk and skimmed milk.

- Be able to boil or coddle or poach eggs properly.

- Be able to select meat and prepare the cuts for broiling, roasting and stewing OR be able to clean, dress and cook a fowl.

- Be able to make two kinds of quick bread, such as biscuits or muffins.

- Be able to plan menus for one day, choosing at least three dishes in which leftovers may be utilized.

From: Useresourceswisely.com