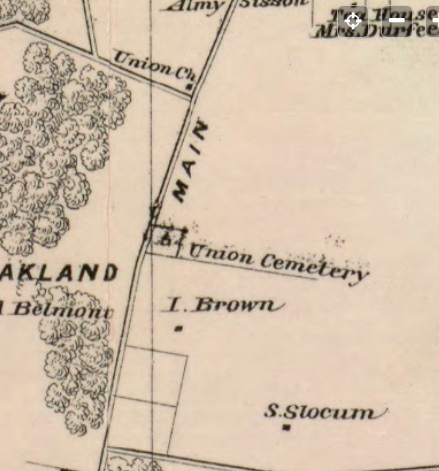

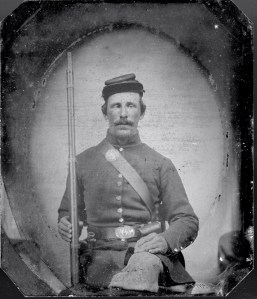

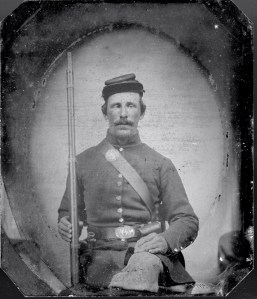

David Durfee Sherman in Civil War Uniform

Among the prize possessions of the Portsmouth Historical Society are the diaries of David Durfee Shearman. Shearman (or Sherman) was a jack of all trades and he recorded everyday life in Portsmouth. We only have the records of a few years, but the 1858 volume provides a wonderful description of how the “Sherman Mill” was moved from Fall River to a spot on Quaker Hill in Portsmouth. The mill had a history of moving from place to place. It was constructed in Warren around 1812 and then moved to Fall River. Shermans moved it to Quaker Hill and then to LeHigh Hill. It was finally moved to Prescott Farm by the Newport Restoration Foundation (NRF). NRF says that Robert Sherman moved the mill to Portsmouth, but Sherman’s diary names his Uncle John Sherman as the owner who moved it.

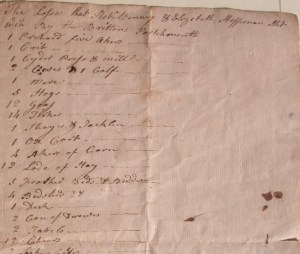

From Sherman’s 1858 diary:

May 5: ..Uncle John has bought a windmill in Fall River and I and Jonathan Sherman has contracted to take it down and move it here on his land west of the main road – and put it up again. It was moved from Warren to where it now stands.

May 15: Helped Jonathan Sherman unload the top of the Mill about 9 o’clock. He brought it in 6 parts, sawed through from top to the plates. At one load with 4 horses.

May 31: Built wall for Father, he went to Fall River with John and Jonathan Sherman to help take down the Mill. They got three sides down and brought them home…

June 1: Built wall for Father. Uncle John’s hired man has been there two days helping us. Uncle having Father’s Oxen to get after the Mill…Jonathan did not get home until 3 o’clock in the morning with the loads of mill.

June 8: Helped knock the shingles off the sides of the Mill AM. They are going to take them all off and nail the boards on firm then lay the same shingles again.

June 11..went up where the men was at work with the Mill. helped them some about raising the poles to make a derrick to put the mill up with. They are near 50 feet long. The bottom of the Mill is laid and some of the sides ready to put up. Four men at work on her.

June 14..Jonathan raised two sides of the mill today.

June 17. Went up to the mill awhile and helped some. They have got up all the sides but one.

June 25. I worked for Jonathan on the Mill – shingling some and putting together the driving wheel on the main shaft.

June 26: I worked for Jonathan today, putting on the top of the Mill. Got it all on. Uncle is going to have it new shingled.

July 14…I went up to Uncle’s Mill afternoon – put up the arms. I helped some. They have got the machinery all put up and will finish it in a short time.

July 22.. Jonathan Sherman finished Uncle’s Mill today. He had $500 for moving and putting it up in running order.

August 13: I sawed some wood that Uncle exchanged with me for white oak, to make pins for his Mill. ….

August 15: Worked on Uncle John’s Mill sails patching and sewing up the rents.

August 17: … Finished mending the sails. Jonathan Sherman came out from Newport and Mr. Borden came in the stage from Fall-River to get the mill in running order to grind corn. Mr. Borden was the owner of the Mill when Uncle bought her. We went up and took up the Big stone (Runner) found that we should have to have the bed-stone to make the wheels gearing to each other.

The runner stone of Boyd’s Mill

Note: The “bed-stone” was set into a bed of concrete to keep it from moving. The “runner” is the top rotating stone. Both stones have a pattern of grooves that direct the grain to the outside edge. The stones don’t touch each other and the grain is cut in a scissor like motion over and over again as they go from the center to the edge.

August 18: Cut away the floor and moved the bed stone just on the Runner. Rigged the sails the afternoon and started her up for the first time in 4 years. A damp, strong south -west wind – she went off start with sails reafed; ground about 5 bushels of southern corn for feed – some was mixed with oats. Levi Cory bought two grists. The first that was bought.

Picks and tools for sharpening the grooves

August 19: We took up the Millstone and picked it with the small picks, shaving 25 or 30 of them together, making the surface of the stone much finer than the old way of picking with a single pick and not taking a quarter of the time to do it. We started up and ground a little at night, but wind light from northwest.

Note: Stone dressers would come at least once a year to “re-face” the stones to keep the grooves sharp. Picks were used to sharpen the grooves.

August 20: Had to move the small bed-stone about an inch. wedged around it again: Worked a good while to make the break clear the driving wheel, and doing other small jobs. Started up the Mill and ground 6 bushels flat corn, making fine meal for John Eldred of Newport: got 6 cents a bushel for grinding it; wind south west, whole sail breeze.

August 21: Isaac Grinnell came and set up the curb around the small stone (it is made of staves and hooked), and done one thing or another about the Mill. A fine clear day, wind west, light.

Sherman Mill today at Prescott Farm

August 23: Worked on the Mill – wedging the arms of the driving wheel to keep it firm and strong. Asa Tibbets was there and assisted us. Jonathan left many things undone which was needed to be done. Started up and ground 13 bushels of corn for feed, one bushel of round corn for Father, and one bushel of eyes in less than two hours, wind blowing strong from west nor west..