Transcribing Revolutionary War era documents was one of my first volunteer activities for the Portsmouth Historical Society. At that time I was working with the original documents in my hands. Today I usually work from a digital image of the document and that makes it easier. On my computer I can enlarge the image of the document and that helps me to decipher what the text is. Because we can make digital images, transcribing documents is something people can do on there own at home. One of our best transcribers works from Georgia! She enjoys this work because she is a genealogist and she sometimes comes across the names of her Portsmouth ancestors as she works. We have hundreds documents from the 1600s and 1700s digitized (we have jpgs of them) and we are working at preparing more documents from the 1700s and 1800s ready to be photographed.

The more I transcribe, the better I get at deciphering the script. It is a skill that comes with practice. Here are a few tips that may help you if you work with transcription.

Glance over the whole document before you try to transcribe. Is it a will, a bill, a court case, a death inventory or another type of written work? The type of document gives us clues to what kind of words you will encounter. If it is a property inventory you are going to see household goods. The bill for construction of Southermost School is going to have building supplies. Legal documents may have special phrases used in the law. Some of the questions we ask are who wrote this, when did they write it, and why did they write it? Thinking of these questions ahead of time actually helps me to transcribe more easily.

Lines should break in the exact same place as on the original. That will make it much easier to move from original to transcription because they will literally “line up” the same.

Type the words exactly as you see them. Keep the original spelling, even if you would consider it wrong. Punctuation, capitalizations (or lack of them) should be like the original. Include everything – cross outs, words added, what is in the margins.

Take your time. Transcribing is puzzle solving and you won’t get all of it at one time. Keep coming back to it. It is often helpful if at least two people are working together on a transcription.

Write down what you can easily decipher first. If you find something you can’t read, leave a space for it and continue on. Go ahead, make a guess. If you are making a guess, put it in brackets with a [?] . Keep saving your work as you go along. You can go back to it and fill in words you missed earlier. Maybe someone later can determine what word belongs in that spot. I look at the words I can decipher as examples of how letters are written by this author.

Sound out the words that are puzzling. Sometimes the odd spellings can confuse us, but trying to sound out the syllables aloud gives us more of an idea of what the word is. Once I have a letter for letter copy, I often try to write it again in modern English.

A cautionary story about dating documents

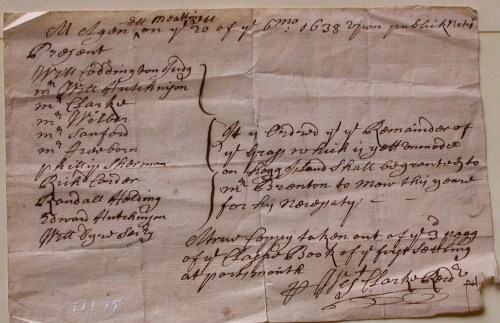

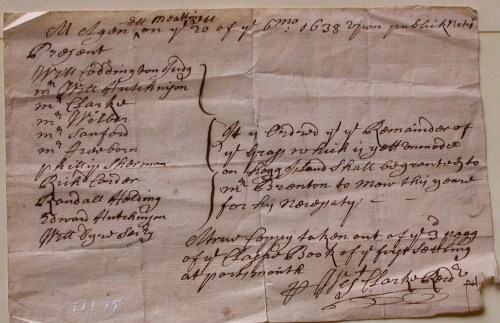

At the Portsmouth Historical Society we have an early copy of one of the first Portsmouth documents. It is about rights to the hay on Hog Island and transcribing it sent me on quite a journey. When I transcribe I usually find myself using secondary sources to look up people and items mentioned in the document. A list of the signers of the Portsmouth Compact provided me with candidates for signers of this document because both documents originated within a few months of each other.

One of the first puzzles concerned the date of the document – the 20th of the 6th month of 1638. At first it sounds like it would be June of 1638. But the right to the hay was given to William Brenton and he wasn’t in Portsmouth in June of 1638. Until 1752, Americans used the Julian Calendar (named after Julius Caesar). The year began in March, so the first month was March and the sixth month would be August. Using numbers instead of names like March, April, May etc. was especially common in Quaker records. There are records of William Brenton being in Portsmouth by August of 1630. There are still mysteries about this document. I know that it is a “true copy” of the original document, but I am not sure if the “Clarke” signing it just means “clerk” or if an actual “Clarke” had made the copy.

transcriptions – hog island – 111.15

Hog Island Hay Document

! meatting myse

met again ^ on the 20 of the 6th mo:1638 upon publick notice

Present

Will Coddington Judg Mr. Will Hutchinson Mr. Clarke

Mr. Wilbor

Mr. Sanford

Mr. Freeborn

Phillip Shearman Rich Carder

Randall Holden Edward Hutchinson, Will Dyer —–

It is ordered yt ye remainder of the hay which is yet —-on Hogg Island shall be granted to Mr. Brenton to mow this year for he neiey aty —— a trew coppy taken out of the 2/3 page of the Chapp Book of the first sotkmg at Portsmouth.

___ ___ ___ ye Clarke —re —-ro

_________________________________________________

My attempt at modern English

! meeting house

Met again v on the 20th of the 6th month; 1638 upon public notice

Will Coddington, Judge

Mr. Will Hutchinson

Mr. Clarke

Mr. Wilbore

Mr. Sanford

Mr. Freeborn

Phillip Shearman

Rich Carder

Randall Holden

Edward Hutchinson

Will Dyer

William Coddington, William Hutchinson, Jr. [husband of Anne Hutchinson], John Clarke, Samuel Wilbore, John Sanford, William Freeborne, Phillip Shearman, Richard Carder, Randall Holden, Edward Hutchinson,William Dyer.

It is ordered that the remainder of the hay which is yet — on Hog Island shall be granted to Mr. Brenton to mow this year his—–

This is a true Copy ———- taken out of the 2/3 pages of the Chapp Book of the first — at Portsmouth

The Clerk _________________________________________