A continuation of Sullivan’s letter to the Continental Congress which was published in the Providence Gazette, September 26, 1778.

The stage was set for the Battle of Rhode Island. Sullivan goes on to describe what happened.

August 29, 1778

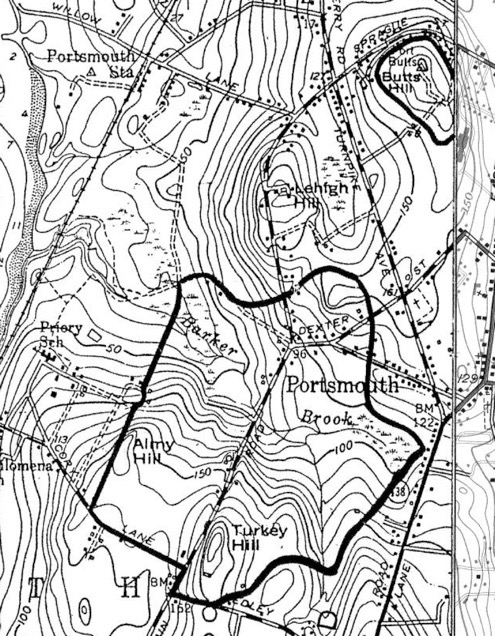

“The enemy having received intelligence of our movement, came out early in the morning with nearly their whole force, in two columns, advanced in the two roads (East Main and West Main) and attacked our light corps; they made a brave resistance, and were supported for some time by the piquet. I ordered a regiment to support Col. Livingston, another to Col. Laurens, and at the same time sent them orders to retire to the main army in the best order they could; They kept up a retreating fire upon the enemy and retired in excellent order to the main army. The enemy advanced on our left very rear, but were repulsed by General Glover; They then retired to Quaker Hill. The Hessian columns formed a on chain of hills running northward from Quaker Hill. Our army was drawn up, the first line in front of the works, on Butts’s Hill, and the second in rear of the hill and the reserve near a creek, and near half a mile off the hill line. The distance between these is about one mile. The ground between the hills is meadow land, with tree and of wood. The enemy began a cannonade upon us about nine in the morning, which was returned with double force. Skirmishing continued between the advanced parties til near ten o’clock, when the enemy’s two ships of war and __armed vessels having gained our right flank and began a fire, the enemy bent their whole force that way, and endeavored to turn our fight under cover of ship’s fire, and to rake the advanced redoubt on the right: They were twice driven back in great confusion; but a third trial was made with greater numbers and with more resolution which, had it not been for the timely aid sent forward would have succeeded. A sharp conflict of near an hour ensued, in which the cannon from both armies placed on the hills, played briskly in __ part of their own party. The enemy were at length routed, and fled in great confusion to the hill where they first formed, where they had artillery and some works to cover them, leaving their dead and wounded in considerable numbers behind them. It was impossible to be certain of the number of dead on the field, as it could not be approached by either party without being exposed to the cannon of the other army. Our party recovered about twenty of their wounded, and took near sixty prisoners, according to the best accounts I have been able to collect; amongst the prisoners is a Lieutenant of grenadiers. The number of their dead I have not been able to ascertain, but I know them to be very considerable. An officer informs me that in one place he counted sixty of their dead. Col. Campbell came out the next day to gain permission to view the field of action, to search for his nephew, who was killed by his side, whose body he could not get off, as they were closely pursued. The firing of artillery continued through the day, and the _ with intermission six hours. The heat of the action continued near an hour, which must have ended in the ruin of the British army, had not their redoubts on the hill covered them from further pursuit. We were about to attack them in their lines, but the men’s having had no rest the night before, and another to eat either that night or the day of the action, and having been in constant action through most of the day, it was not thought advisable, especially as their position was exceedingly strong, and their numbers fully equal, if not superior to ours.”

Sullivan writes about how well his troops functioned, even though they had little experience.

“Not more than fifteen hundred of my troops had ever been in action before. I should before have taken possession of the hill they occupied, and fortified it, but it is in no defense against an enemy coming from the south part of the island, though exceedingly good against an enemy advancing from the north and towards the town, and had been fortified by the enemy for that purpose.

I have the pleasure to inform Congress, that no troops could possibly show more spirit than these of ours which were engaged. Col. Livingston, and all the officers of the light troops, behaved with remarkable spirit; Colonel Laurens, Fleury, and Major Talbot, with the officers of their corps, behaved with great gallantry. The brigades of the first line, Varnum’s Glover’s Cornell’s and Greene’s behave with great firmness. Major-General Greene, who commanded in attack on the right, did himself the highest honor, by the judgment and bravery exhibited in the action. One brigade only of the second line was brought into action, commanded by Brigadier-General Lovell; he, and his brigade of militia, behaved with great resolution. Col. Crane and the officers of the artillery deserve the highest praise.”

Sullivan writes about the casualties:

“I enclose Congress a return of the killed, wounded and missing on our side, and beg leave to assure them, that, from my own observation, the enemy’s loss must be much greater. Our army retired to camp after the action; the enemy employed themselves in fortifying their camp at night. “

Sullivan justifies the retreat: Lord Howe and his fleet were approaching.

In the morning of the 30th I received a letter from his Excellency General Washington, giving me notice that Lord Howe had again sailed with the fleet, and receiving intelligence at the same time that a fleet was off Block Island and also a letter from Boston, information me that the Count D’Estaing could not come round so soon as I expected, a council was called, and as we could have no prospect of operating against Newport with success, without the attendance of a fleet, it was unanimously agreed to quit the island until the return of the French squadron.

The retreat plan is shared with Congress

To make a retreat in the face of an enemy, equal, if not superior in number, and cross a river without loss, I knew was an arduous task, and seldom accomplished, if attempted. As our sentries were within 200 yards of other, I knew it would require the greatest care and attention. To cover my design from the enemy, I ordered a number of tents to be brought forward and pitched in sight of the enemy, and almost the whole army employed themselves in fortifying the camp. The heavy baggage and stores were falling back and crossing through the day; at dark, the tents were struck, the light baggage and troops passed dawn, and before twelve o’clock the main army had crossed with the stores and baggage. The Marquis de la Fayette arrived about 11 in the evening from Boston, where he had been by request of the general officers, to solicit the speedy return of the fleet. He was sensibly mortified that he was out of action; and that he might not be out of the way in case of action, he had rode from hence to Boston in seven hours , and returned in six and a half, the distance near seventy miles — he returned time enough to bring off the pickets, and other parties, which converted the retreat of the army, which he di in excellent order; not a man was left behind, nor the smallest article left. I hope my conduct through this expedition may merit the approbation of Congress. Major Morris, on of my aids will have the honor of delivering this to your Excellency; I must beg leave to recommend him to Congress as an officer who is in the last, as well as several other actions, has behaved with great spirit and good conduct, and doubt not Congress will take such notice of him, as his long service and spirited conduct deserves. I have the honor to be, dear Sir, with must___

Your very humble servant – John Sullivan.

_