I have been doing some research on Maud Howe Elliott as I learn about the women of the Newport County Woman’s Suffrage League. As I read Maud’s book – This Was My Newport – I came across much about her childhood summers in Portsmouth. She details a very interesting memory of visiting Lovell Hospital.

The Howe family summered at a house off of East Main Road by Lawton Valley. When Howe was around seven or eight, she decided to run away with a boy who lived on the Redwood Estate (where Redwood Farms is today.) She walked down the valley to the shore, pass the Portsmouth Asylum (the location of Raytheon) and to the railroad tracks by the shore. They two children were headed for Portsmouth Grove where the Providence boat stopped to take on and leave passengers.

The two “tallerdemalions” (as she called them) were confronted by a sentry for Lovell Hospital. “Who goes there? Halt!” Two sentries pacing their beat at the entrance of the military hospital grounds crossed their bayonets above the young couple’s heads and proceeded to chaff them. Then, relenting, the good natured soldiers returned to their beat while the children wandered down the broad middle path between the oaks and the hospital tents to the boat-landing. One point of dread they touched: a place of torture, where, in a small shed, a culprit stood with water falling drop by drop upon his head…”

The steamer “Perry Mail” was at the dock, but the children didn’t have any money for the fare. The sun was setting and the sentries told them to “put for home, young ones, as tight as you can go.” The long road climbing the steep hill from Portsmouth Grove was trim and well-kept, then. The children soon reached the summit, and turned for one last look at the camp with its white tents gleaming among the dark trees. The bugle sounded, the sunset gun boomed, and the “Flag of our State Battles” came at a run down the tall flagstaff.

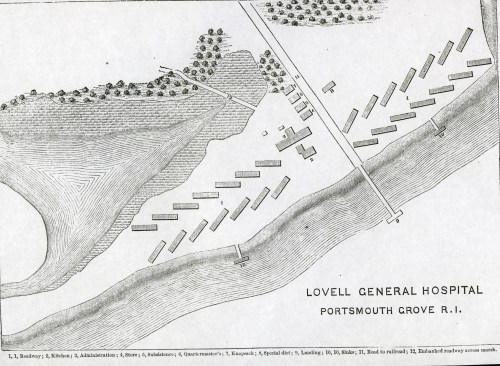

The Portsmouth Grove House had became the administration building for the Lovell Hospital. The hospital, built in 1862, cared for wounded Union and Confederate troops. Again, these soldiers arrived at Portsmouth Grove by steamships. The Rhode Island Hospital Guard which was made up of soldiers too disabled for battle, kept the peace and watched over prisoners. After the war the hospital was dismantled and there are no signs of it left.

More on Lovell Hospital coming in feature blogs.

Resources:

Frank L.Grzyb has written a book, Rhode Island’s Civil War Hospital: Life and Death at Portsmouth Grove.

Elliott, Maud Howe: his Was My Newport. Cambridge, Mass, Mythology Company, 1944.