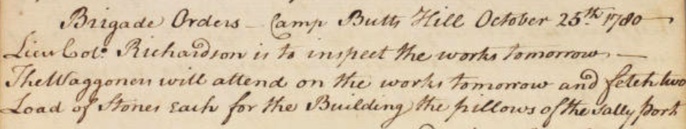

This is a continuation of information in Thayer’s Orderly Book that covers what was going on at Camp Butts Hill. This is not a transcription, but it is notes on the information provided. This book ends at the end of October when the brigade leaves Camp Butts Hill. The orderly book helps us understand the cooperation between the French masons and engineers who are working on Butts Hill Fort and the Americans who are aiding in this building project.

October 2, 1780: The main guard will consist of one captain, one “subb (Subaltern-like a second lieutenant),” two sergeants, four corporals and 48 privates. There was concern that the “property of the inhabitants be secured” and public property be guarded. Captain Devol wants one boat builder and one caulker to assist him in repairing the public boats from this port.

October 3, 1780: The drum major and fife major will practice two hours a day with the drummers and fifers.

October 4, 1780: Commanding officers of each brigade should insure that there are enough provisions on hand “that they may be always fit for duty.” At least one day’s provisions is required to be on hand. In letters from Camp Butts Hill we find that hunger was a real concern. The drum major is to start the beat for reveille at first light for the guard and the drummer should sound the beat through the whole camp. Lieutenant Waterman will receive directions for removing the small barracks which stands at Butts Hill Fort.

October 6, 1780: Cartridge boxes in tents will have names of commanding officers and be taken to the magazine in the fort. Kitchens were built in front of the tents and high so smoke doesn’t get to the tents. There will be a regimental court martial for James Stanford of Captain Hodge’s group of Thayer’s regiment. The charge was insulting language to the Captain. Found guilty, 15 lashes on a naked back will be administered and the guilty party must ask pardon of the Captain in the presence of the commanding officers. “It is Col. Commandant Greene’s pleasure that one Field Officer shall inspect the works at Butts Hill Fort. They will attend the works in rotation.”

October 7, 1780: Lt. Col. Hallet will supervise the “works” – the work being done on Butts Hill Fort.

October 8, 1780: Lt. Col. Clap will inspect the works. Henry Hilman is accused of desertion. He “shall be drummed out of the brigade with his Hatt under his arm.” The Bristol Ferry Commanding Officers will make a report to the officer of the day.

October 12, 1780: There were complaints of too many soldiers in Newport. They will now need a pass. “It is requested by General Rochambeau and Commander Jacobs that every officer not on duty will attend upon the works for the purpose of encouraging the soldiers and completing the fort.”

October 16, 1780: “There are four men to be detached from the brigade to attend constantly on the French Masons until the stone pillows of the Fort are completed and two masons detached to assist the French Masons until the works are finished and for their service they shall receive half a pint of rum a day when in the store.” Their provisions are ready for them so that they can complete the Fort works in a timely manner.

October 17, 1780: The commander has been informed that “the inhabitants have had a large number of fowls taken from them” supposedly by the soldiers. Those caught stealing from the inhabitants will be punished. “The wagon masters of the brigade are directed to attend on the works with their wagons at the time the fatigue party goes on the works and fetch one load of stones each for the purpose of building the pillows of the fort.

October 19, 1780: The French are getting wood at Freetown and are in need of the American flat bottom boats.

October 25, 1780: The American wagons are bringing loads of stone to the works at Butts Hill Fort. They are building a “sally port” which is a secure, controlled entry way to an enclosure like a fort. All tools must be returned to the engineer.

October 26, 1780: Jacob’s regiment is leaving and his men are requested to return the tools they have borrowed from the French. They will return them to the engineer. Tents and other equipment are to be returned to the quartermaster.

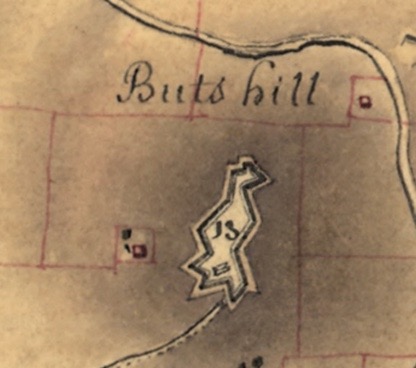

Map:

Plan de Rhodes-Island, et position de l’armée françoise a Newport.

Created / Published

(1780)