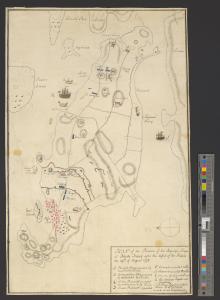

As the memorial stone at Butts Hill Fort reads, it is important for us to honor the “memory of those brave men who” fought in the Battle of Rhode Island”. It is also important for us to remember the Portsmouth women and their families who endured almost three years of British Occupation from December of 1776 to October of 1779. When the Portsmouth Town Council was able to meet again in 1779, the members pleaded with the state to have pity on us because the town was in a “Distressed Situation.” As I research this Revolutionary Era in Portsmouth history, the plight of Portsmouth women and their families was indeed disstressed.

What was Portsmouth like when the British came? The diary of British soldier Frederick Mackenzie provides a rosy picture. “There is a hill about 7 miles from Newport, and on the Eastern side of this Island called Quaker Hill, from there being a Quaker meeting-house on it, from whence there is a very fine view of all the N. part of the Island, and the beautiful bays and inlets, with the distant view of towns, farms, and cultivated lands intermixed with woods, together with the many views of the adjacent waters, contribute to make this, even at this bleak season of the year, the finest, most diversified, and extensive prospect I have seen in America.” This fine prospect did not last long under British military control. Much has been written about Occupied Newport, but the situation in Portsmouth had its own set of troubles. At times citizens were allowed to leave the island, but if you were a Portsmouth farm family you stayed to work and protect your farm. There were many Loyalists in the commercial port of Newport, but the majority of families in Portsmouth leaned towards the Rebel side. Only about ten percent of Portsmouth citizens left the island.

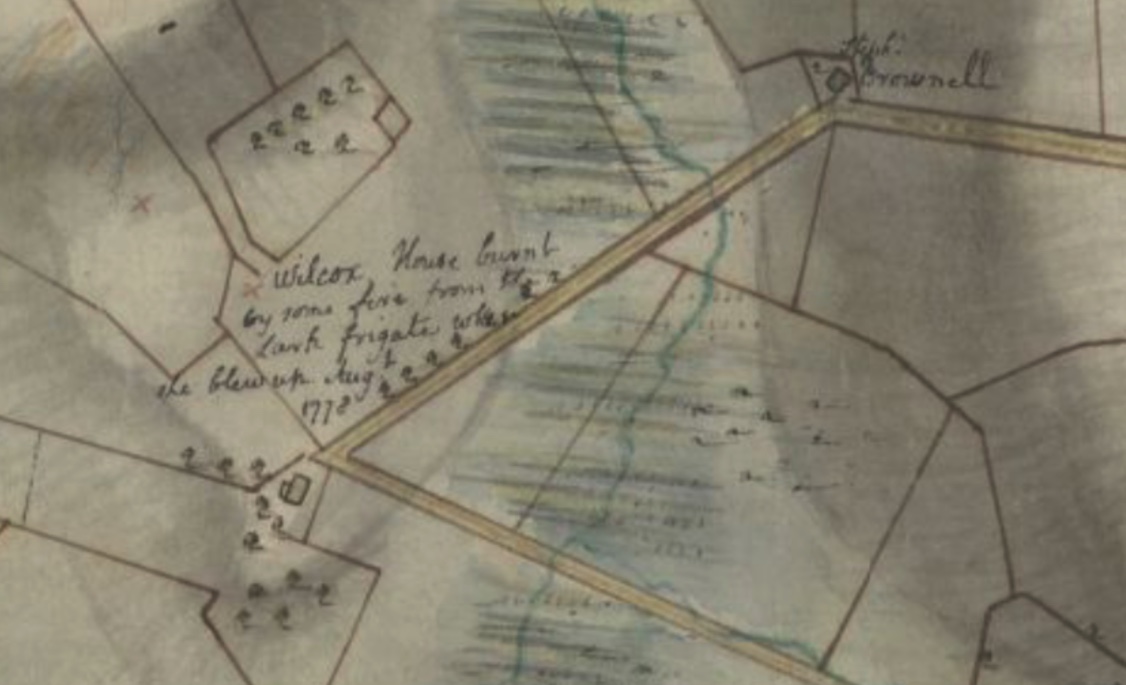

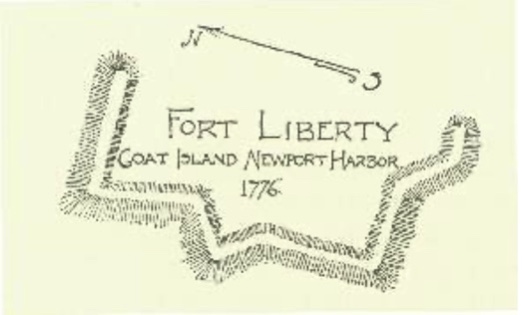

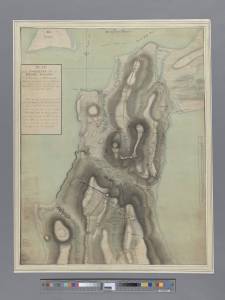

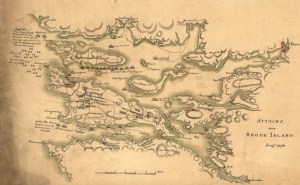

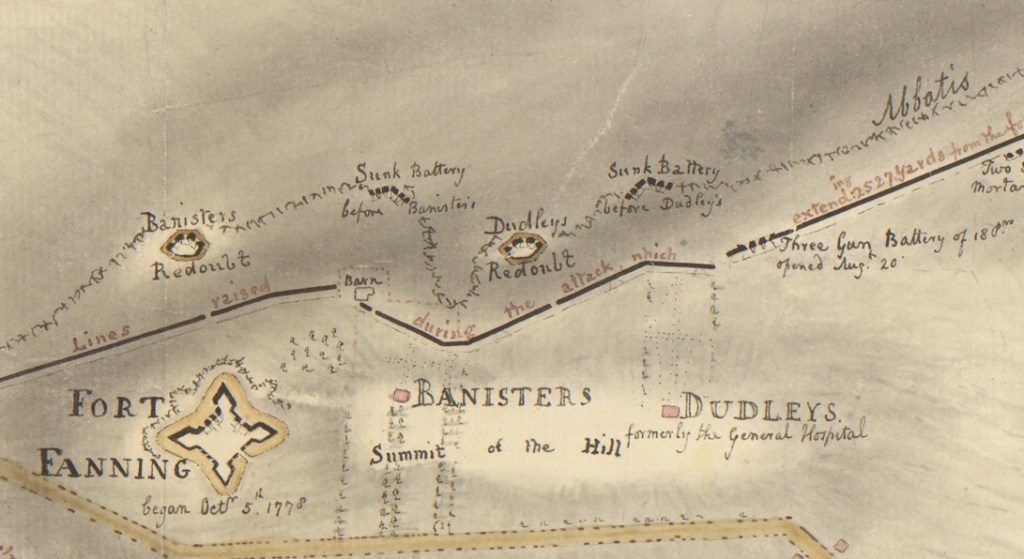

What happened to Portsmouth women and their families when the British arrived? British maps from the Revolutionary Era give us some idea.

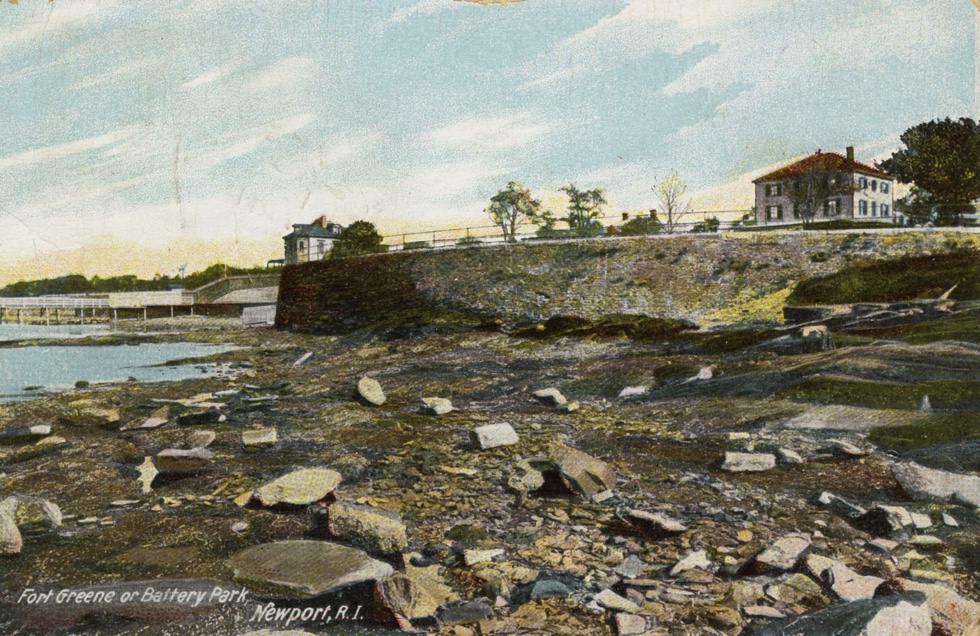

- Some families lost their homes. For example, the British fortified Bristol Ferry and they tore down homes that blocked their vision of the ferry landing. Some houses were taken over as barracks for troops or as housing for officers and generals.

- Almost all families lost their trees and orchards. As time went by just about every tree on the island was cut down for firewood. The families were left in the cold while the British warmed their troops.

- Farm families lost their livestock. There were many soldiers to be fed. Mackenzie’s diary says the British left families with a means of feeding themselves. They could keep one gun to hunt birds and they could keep a boat for fishing.

- The British took just about every wagon and wooden farm tool. Wooden vehicles were used by the British for carrying loads, and almost anything wooden was burned for fuel.

- Women assumed greater responsibility to care for their families. With the exception of Quaker families, almost all Portsmouth men served some time in the American cause. Even those who were on the island during the Occupation were impressed into service by the British to work on fortifications on Butts Hill and elsewhere.

- When the British left the island they filled in just about every well – the source of water for families.

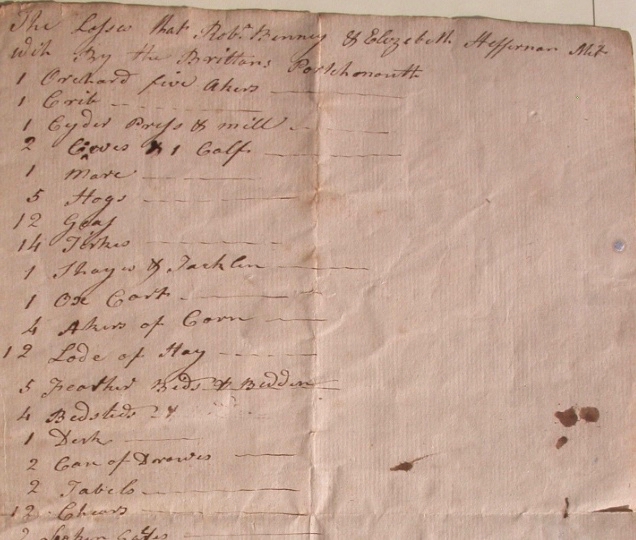

At the withdrawal of British troops in 1779, Portsmouth farm families had a difficult time getting their farms back into operation. Families listed their losses in hopes of getting some reparations. One of these lists is in the collection of the Portsmouth Historical Society. It gives us an idea of how devastating the household losses were. This list shows the losses of Edward Binney and Elizabeth Heffernan – in-laws who lived in a joint household just north of the Friends Meeting House on Quaker Hill.

Among the losses:

Livestock: 2 cows, one calf, 5 hogs, 12 goats, 1 jackass

5 acres of orchards, a cider press and mill, 4 acres of corn, 12 loads of hay,

Farm tools: An ox-cart, 3 hoes, forks, 2 spades

Household goods: desks, beds, drawers, wood cards, kettles, pots, gowns, tablecloths, etc.

It is clear that we should honor the brave Portsmouth women who cared for their families under such difficult circumstances.