For over sixty years the Newport Chapter of the National Associate of Colored People (NAACP) has been calling attention to the valor of the soldiers of the First Rhode Island Regiment (called the Black Regiment). I heard the story of their efforts at last year’s commemoration of the Black Regiment’s efforts in the Battle of Rhode Island. Mrs. Fern Lima recounted all the milestones in the NAACP’s efforts to create a memorial to these soldiers and to continue to tell their story. Mrs. Lema’s presentation is from the notes of her father, Lyle Matthews, a past NAACP president and one of the earlier workers in the effort. I recently had the opportunity to talk to longtime Newport County NAACP members, Mrs. Lema and Mrs. Victoria Johnson. I had gathered a timeline from newspaper articles, but they had been participants and could give me their personal perspectives.

One of the key information sources Mrs. Lema provided was a copy of the program for an earlier monument dedicated in 1976. In the booklet for the Dedication, May 2, 1976, NAACP President William Trezvant quoted from historian Charles A. Battle’s booklet “Negroes on the Island of Rhode Island”.

“In August 1928 the one-hundred and fiftieth Anniversary of the Battle of Rhode Island was fittingly celebrated by the citizens of Rhode Island. At that time the suggestion was made that the State of Rhode Island honor in bronze or stone the memory of Colonel Greene’s regiment.”

The dedication of the Black Patriot’s Monument in 1976 was just one milestone in a larger effort to bring the story of the Black Regiment to the attention of Rhode Island and the nation. In an earlier letter (Nov. 12, 1975) Trezvant wrote: “The Goal is to have the Black Regiment take its rightful place in Rhode Island History and in the Nation’s fight for freedom.” Early steps toward that goal were made by historian Charles Battle and those who researched the role of the First Rhode Island Regiment. NAACP members Lyle Mathews, John Benson and State Senator Erich O’D. Taylor did the spade work in determining where the redoubt was located that the Black Regiment defended so valiantly. Mathews was President of the NAACP at the time and Fern, his daughter, remembers field trips out to the Bloody Run Brook area where the men scouted a location that would be an appropriate site for a monument. One of the men, John Howard Benson, was a noted carver and created a woodcut map of the Battle with the redoubt’s position marked with a star. This beautiful map was included in the program.

Mrs. Lima and Mrs. Johnson helped me with a timeline of the events in the completion of Patriot’s Park.

In 1967 the NAACP began an annual celebration of the valor of the Black Regiment and to call attention to their role in history. In July of that year a boulder on the property was dedicated to the Black Regiment. State Senator Taylor was master of ceremonies and he introduced Oliver Burton who knew Charles Battles and was an early advocate for recognition of the Black Regiment’s role in history.

In 1969 the remembrance was held in August and a flagpole was added to the site. Children who had learned about the regiment from Battle’s book attended and Oliver Burton spoke. Both Mrs. Johnson and Mrs. Lima have their own copies of Battle’s book and having a good history of the story of the First Regiment in the battle was helpful in making the community aware of the special role they played.

In 1972 over 150 gathered at the memorial area on the anniversary of battle. Newspaper accounts state that this was the 9th annual commemoration organized by the NAACP.

In 1973 a large portion of the battleground was named a national historic site. This portion of the battlefield was called “Patriot’s Park.” At this time the site contained a small monument designating the historical site, a flagpole and simple boulder. Ceremonies celebrating the role of the Black Regiment continued to be held there.

In November of 1975 a fund drive was started to erect a monument to Rhode Island’s black patriots of Bloody Brook in Portsmouth. The Newport NAACP raised funds through the sale of commemorative pins. The plans for the monument were that it would be six feet high by 4 inches wide. The insignia of the 1st Rhode Island Regiment would be carved into the granite. The State Department of Natural Resources would prepare the landscape.

May 6, 1976 was the unveiling of a monument at Patriot’s Park. The monument was unveiled by Mrs. Oliver Burton, widow of a man who knew Charles Battle and had dreamed of erecting the memorial Battle had wanted. Plaques were presented to State Senator Erich O.D. Taylor and Dennis J. Murphy of the RI Dept. of Natural Resources for their efforts in the project.

In 1994 funding from the Federal Highway Administration for projects to improve or preserve historic sites associated with the federal highways became available. The Black Patriots Committee of the Newport NAACP and the RI Black Heritage society proposed improving the site.

In 1996 the head of the Rhode Island Department of Transportation (RIDOT), William F. Bundy, selected the Patriot’s Park Landscape Project as the state’s first enhancement project. Paul Gaines was chosen to coordinate the creation of the memorial and he was working with designer Derek Bradford. Gaines and his committee spent 10 years on the project that created a 36-foot-long, 10-foot-high black granite memorial to the First Rhode Island Regiment.

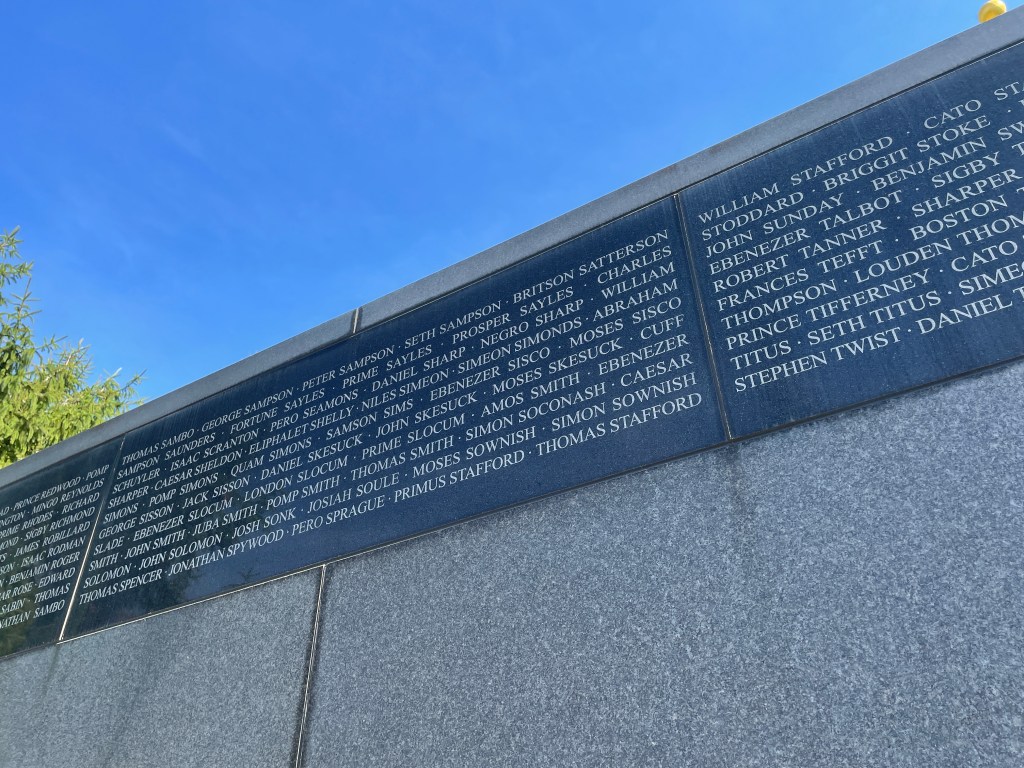

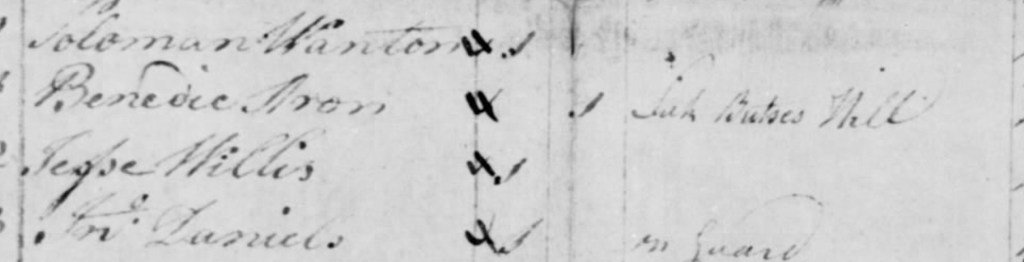

By 1999 Bradford submitted plan for the larger monument. The design was a simple: platform with a wall that has two doorways and names of First Regiment soldiers engraved on the wall. Since no muster rolls were available for those just involved in the Battle of Rhode Island, Bradford agreed to engrave the names of all known members of the regiment.

Federally funded projects require an Environmental Impact Assessment in which groups with direct interest are given opportunity to comment. RIDOT invited 12 groups – Black organizations, Native tribes, local institutions like Rhode Island Historic Preservation and Heritage to comment on the plans. The basic list was the known black soldiers, but the list for inclusion was open to the families of indigenous soldiers and many of those names were added at their family’s request.

By February of 2000, two narratives had been written explaining the creation of the regiment. The battle narrative (written by Carl Becker and Louis Wilson) was agreed upon with corrections. It took 4 years to reach agreement on the following text:3 “And to the soldiers of the Narragansett Indian Nation who fought alongside them.”

In 2006 the Memorial to Black Regiment was dedicated. The story of the valiant efforts of the 1st Rhode Island Regiment (the Black Regiment) is engraved for all to see and the names of these soldiers are remembered.

The efforts to tell the story of the Black Regiment are not over. The cause continues because the Memorial is in need of repairs and funds must be raised to do the required work.

Through the efforts of the NAACP the story of the Black Regiment is being told and there is a dedicated spot on the battlefield to honor their valor at Bloody Run Brook.