On the 19th of July in 1769 a Newport mob was so exasperated with the captain of a sloop owned by Royal Commissioners that they “went on board the Liberty as she lay at Anchor in the Harbour, and cut her cables, and let her drift ashore, they then set her on fire…” (Boston Chronicles, 24, July 1769). This incident was almost three years before the burning of the Gaspee. The Liberty burning has some aspects in common with the Gaspee Affair. Both were protests to the increase in taxation on the colonists. But the roots of the burning of the sloop Liberty have some interesting origins that start with charges brought against John Hancock, the original owner of the Liberty. Liberty’s story begins in Boston.

The Seizure of the Sloop Liberty

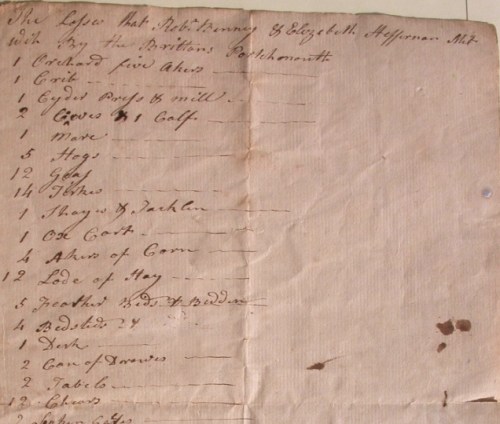

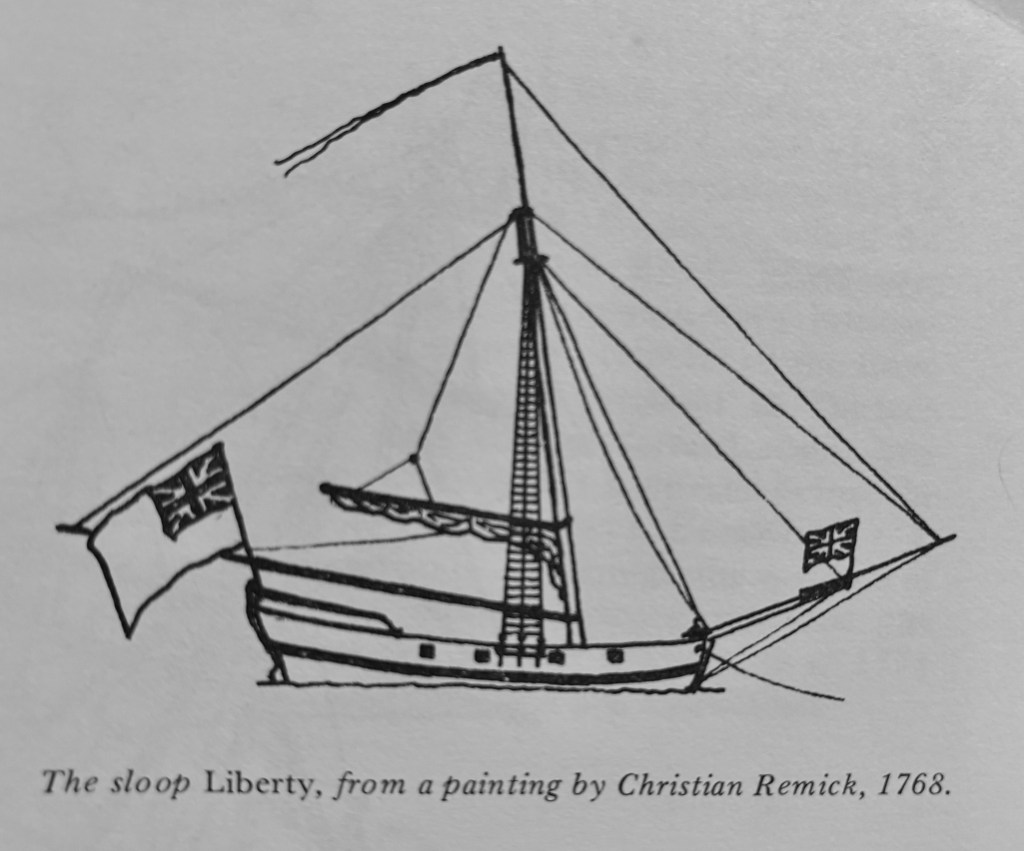

The Revenue Act of 1767, part of the Townshend Acts, placed heavy taxes on goods imported to the colony. The American Board of Customs Commissioners was put in place so that royal officials could inspect incoming merchant vessels and charge the appropriate taxes, but Hancock had refused to allow the officials to inspect one of his vessels – the Lydia. When the customs official was sent to inspect the Liberty, he accused Hancock’s men of offering him a bribe to look the other way while they were unloading. He refused the bribe and he claimed they locked him in the hold of the ship. When news of the incident spread, an angry crowd assaulted the officials involved, broke the windows of their homes and set the officials personal boats on fire on the Commons. The sloop was seized at Boston Harbor on June 10, 1768. John Adams defended Hancock against the smuggling charges. The case dragged on and the charges were later dropped due to lack of evidence. The sloop Liberty, however, had been seized and Hancock could not get it back. It was condemned in August of 1768 and sold in September.

The Burning of the Sloop Liberty

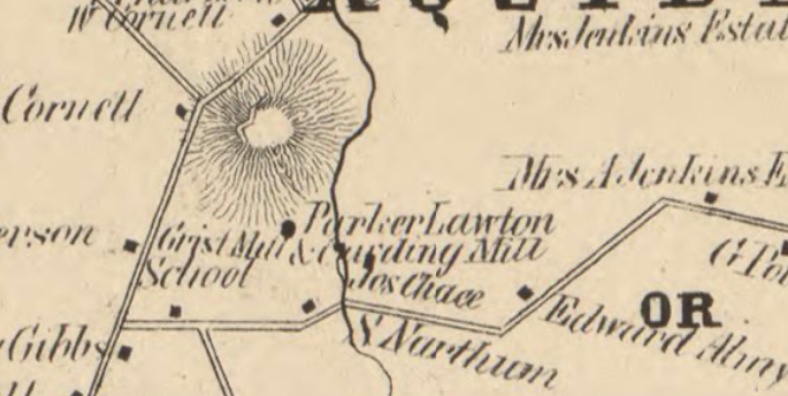

Parliament’s taxation laws hit the New England economy hard, and some turned to smuggling to avoid the taxes. In 1769 the sloop Liberty came into Newport Harbor. It was the same sloop that had been seized from John Hancock. The captain, William Reid, was authorized to capture smugglers and in return he and his crew would receive a bounty. The Liberty was a private vessel hired by the Commissioners of Customs. Reid had the reputation for being overly zealous in carrying out his order. He frequently boarded and searched legitimate merchant ships and delayed their sailing.

On 17 July 1769 the Liberty took a Connecticut-owned brig into custody on Long Island Sound and brought her to Newport. But Reid could not prove the brig had violated any laws. Captain Packwood, the ship’s master, had declared his cargo at the customs house before sailing. Reid’s crew continued to hold the ship in the hopes something else would be discovered to justify their bounty for the capture. Captain Packwood visited the Liberty to take control of his vessel, but shots were fired towards him. Local Newporters became outraged and a crowd gathered. Tempers flared when local officials would not help the Captain get his vessel back. A group of men attacked the Liberty, cutting the sloop’s mooring lines and drifting her down toward Long Wharf. One report is that they cut down her masts and threw her guns overboard. The hulk drifted out of the harbor on the tide and came to rest on Goat Island, where another mob set her ablaze.

This is the account of the burning in the Boston Gazette – July 24, 1769.

“We hear from Newport, Rhode-Island, that last Monday the Sloop Liberty, Capt. Reid, said to be owned by the Commissioners, brought in there a Brig and a Sloop belong to Connecticut, that they had for some pretext seized in the Sound, which, together with the impudent behavior of the Captain and some of his People, so exasperated a number of persons there, that on Wednesday afternoon they went on board the Liberty as she lay at Anchor in the Harbour, and cut her cables, and let her drift ashore, they then set her on fire but being informed a considerable Quantity of Powder was on board, for fear of endangering the Town, they extinguished it again; they then cut away her mast, threw her guns and stores overboard, entered the Cabin and destroyed the Captains and his wife’s cloaths, bedding, broke the tables, chairs, china and other things therein, and did not quit her til 3 oclock the next morning, when after scuttling the vessel, they left her a meer Wreck, and now remains sunk near one of the wharfs there. They also seized her barge and boat and burnt them – The Brig that was seized we hear was legally discharged on Thursday, but that the Sloop made her escape in the confusion the evening before.”

An 1835 edition of the The Rhode-Island Republican (Newport, R.I.), November 1, 1837 has an in-depth story about the burning. The article starts with an account “related to us by one of the old inhabitants of the town, Mr. Benjamin Hadwin”. Hadwin adds some details of how the crowd was able to get on board the Liberty. The reporter found articles to substantiate. the story. One was from the Providence Gazette of July 22nd, 1769 and it adds more details to what incensed the crowd. The Captain of the brig went on board the vessel to retrieve his sword and other items. When he found a crew member of the Liberty in possession of it, he seized it and made for the shore. Musket fire came from the Liberty directed at the Captain of the brig. Witnesses on the shore saw the attack and Captain Reid had to bring his men on shore to answer for their actions and “a number of men, chiefly from Connecticut, went on board and rendered her unfit for service. ”

Governor Wanton issued a proclamation that officers of justice should bring the persons guilty of the crime of destroying the Liberty, but nothing became of it.

An article dated August 28th, 1769 contains the Order of the Commissioners. It names the sloop Reid brought in as the Sally whose master was Edward Finker of New London. “A reward of one hundred pounds sterling is offered to any person or persons who shall inform against any of the offenders (except Nathanial Shaw, Joseph Packwood and ________ Angell;) to be paid on his or their convictions.” Nathanial Shaw’s family were noted New London merchants and later privateers working for the Americans. The Shaws may have been the owners of the Sally.

An article in the Newport Mercury (July 22, 1769) adds a few more details. Captain Packwood of the brig had “to draw his sword to force his way into his boat whereupon the officer called upon the Liberty’s people to fire on Captain Packwood…” Captain Reid was made to send his men to shore to discover who fired on Packwood and the crowd took that opportunity to board the Liberty.

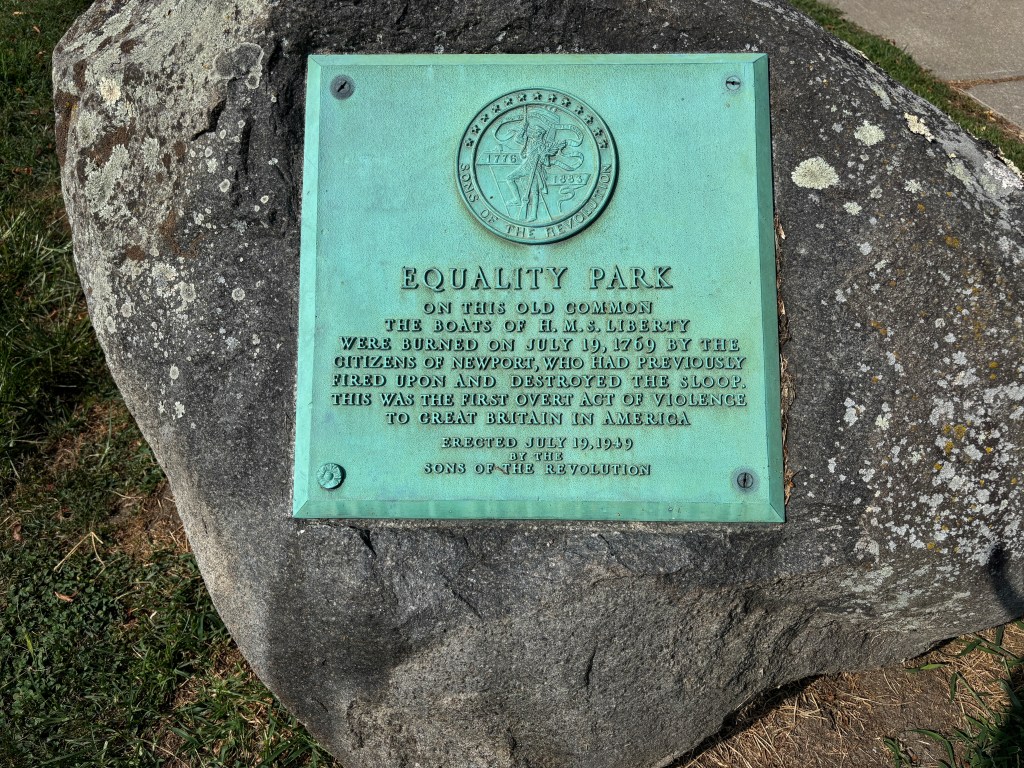

The burning of the barge and the boat the accompanied the Liberty are commemorated with a plaque in Newport today. According to the Rhode Island Republican 1835 article “The Boats were burned on the Common, opposite the Pound. They were run up the Long Wharf, then up the Parade, and through Broad Street by the populace…”

Resources: Website Founder’s archives. https://founders.archives.gov/documents/Adams/01-03-02-0016-0021 – John Adams writes about the case of Hancock’s liberty. Retrieved July 30, 2025

The Magazine of Naval History – February 2016. Retrieved July 30, 2025 https://www.usni.org/magazines/naval-history-magazine/2016/february/act-war-eve-revolution –

https://www.masshist.org/dorr/volume/2/sequence/634 The Boston-Gazette, and Country Journal, 24 July 1769. Retrieved July 30, 2025

Massachusetts in the American Revolution – the Liberty Affair. https://guides.bpl.org/c.php?g=800717&p=10389851

The article in the 1835 Rhode Island Republican can be found through the Library of Congress. Retrieved July 31, 2025.

Virginia Gazette, August 17, 1769. https://www.loc.gov/resource/sn84024741/1769-08-17/ed-1/?sp=1&q=sloop+liberty&r=-0.287,-0.166,0.959,0.498,0. Retrieved July 30, 2025.