In earlier blogs I wrote about a war game or “sham battle” described in the letter of an American doctor (John Goddard) to a colleague. This battle was on October 2, 1780, but there are also descriptions of later mock battles or skirmishes on October 8th and October 11th of 1780. Louis Bertrand Dupont d’Aubevouede Lauberdiere kept a Journal of his experience in the American Revolutionary War. Through the work of Norman Desmarais, we have an English translation – The French Campaigns in the American Revolution, 1780-1783: The Diary of Count of Lauberdiere, General Rochambeau’s Nephew and Aide-De-Camp.

We know through a brief Providence newspaper account that another “battle” occurred on October 8th. Lauberdiere described the battle as being “on the eighth.” In his diary he mentions yet a third of these war games on October 11th. There are some similarities of the mock battle descriptions in both the American and French accounts.

From Lauberdiere’s diary:

“May our comrades arrive soon and draw us out of the somber tranquility in which we live. The soldiers under canvas (tents) want to see the enemy, want to hear the cannon. In the absence of the British, Mr. De Rochambeau created some and, on the eighth he drilled the army on the point where the real enemy might land. We pretended that a fleet entered our harbor and planned a landing.” ( Road to Yorktown.” page 40-41).

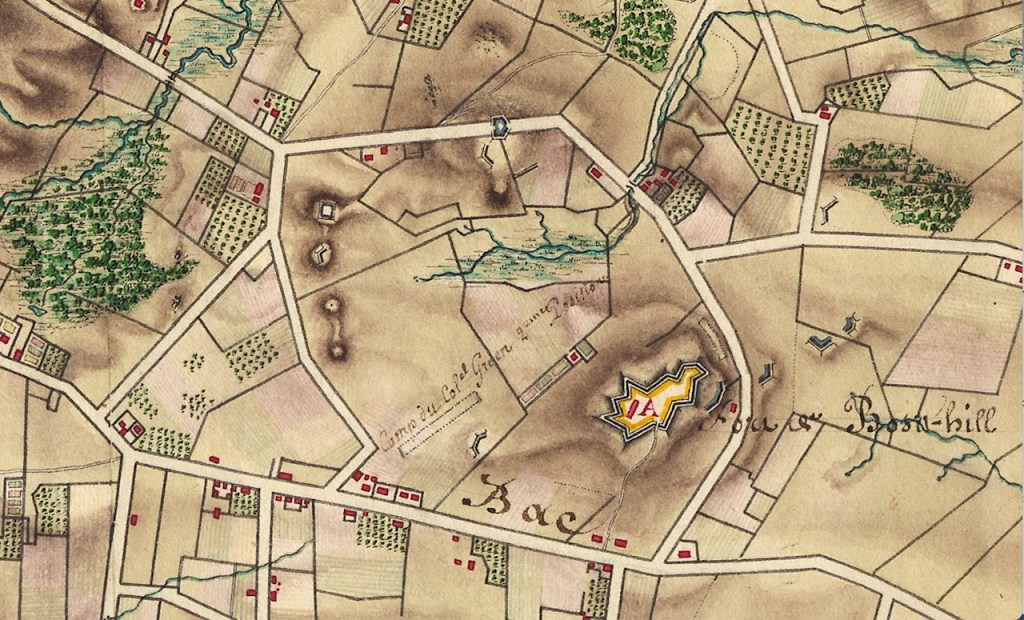

The British ships had been seen near Newport waters and the expectation was that they would invade. Rochambeau picked the location of the British invasion in 1776 as the site for the battle. The diary calls the location “Stauder’s House,” but the actual name was Stoddard. British maps label this location. close to the Middletown – Portsmouth border, as the landing site of the British.

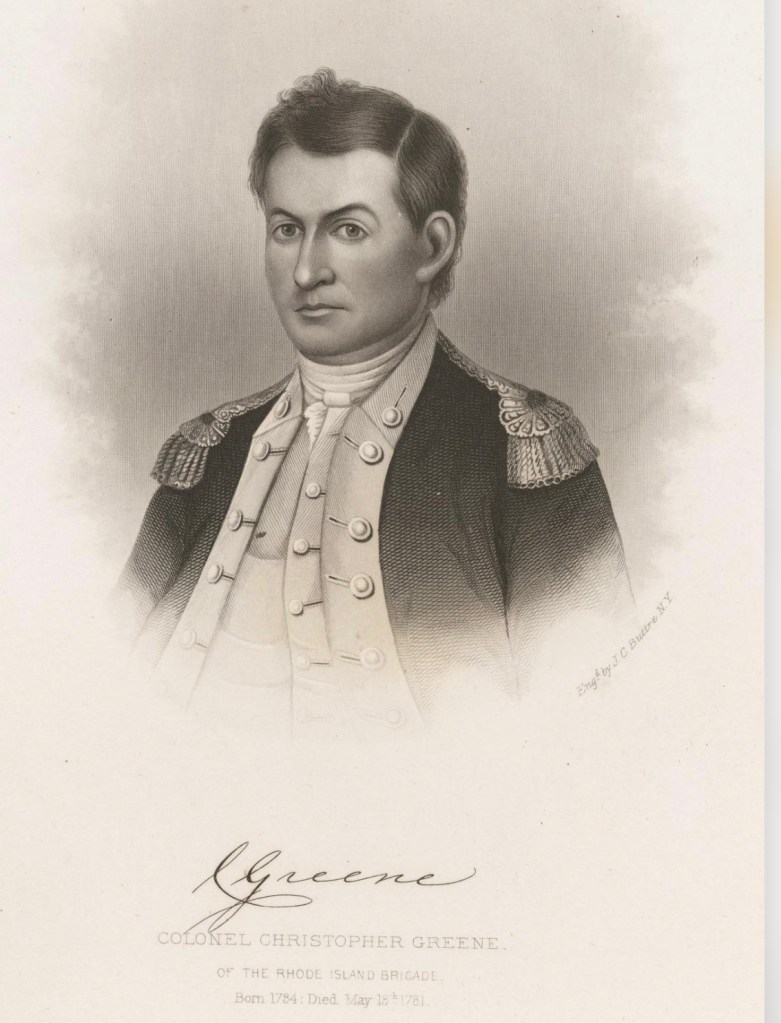

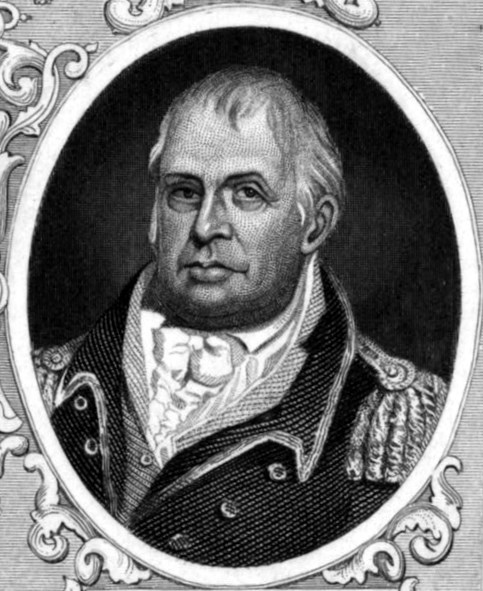

“We put 1500 men under the command of the Viscount de Viomenil who was at Stauder’s house. It was there that our enemies first began to take possession of a few houses along the shore. Mr. De Rochambeau kept the rest of the troops with him for the imminent attack to which he joined the American Rhode Island Regiment commanded by Co. (Christopher) Greene. These troops were divided into two column. Mr. De Rochambeau personally led the left column. The Baron de Viomenil commanded the right. The grenadiers and light infantry battalions formed a separate one.”

In Goddard’s account of the October 2nd mock battle, the American forces, the Rhode Island First Regiment (the Black Regiment), under Col. Christopher Greene, took part in the drill. The French Army did have drills between their own men and some of those may have been in the Third Beach area of Middletown. This drill on the eighth of October was also a drill of combined forces of the Americans and their French allies.

“The attack began with several discharges of cannon, well-executed to create a complete effect of the fictitious enemy leaving their boats and forming quickly. At the same time, the column of grenadiers advanced to dislodge the enemy from the houses as they began to establish themselves there. During this musket fire, the Baron de Viomenil turned their right under the protection of a hill which concealed his movement. When he was ready and the attack was fully engaged, Mr. De Rochambeau had the charge sounded. Everything advanced in good order. The enemy disappeared and reassembled on the seashore.”

An Accident Happens: Lauberdiere’s diary:

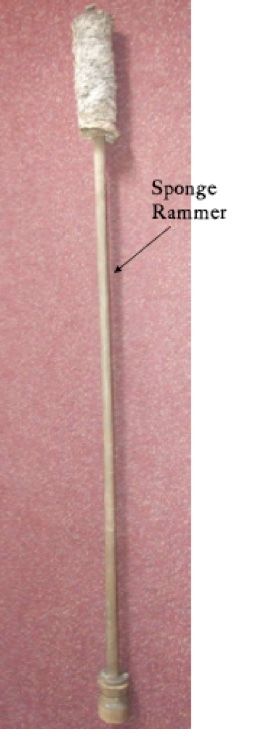

“An accident occurred during this drill. A cannoneer cleaning a piece lost an arm by the sponge. The one who was aiming it had neglected to cover the touchhole with his thumb. An ember remaining from the preceding shot ignited and the charge caught fire.”

During the Revolutionary War a sponge head was used to extinguish embers from the previous firing. The sponge was part of a sponge-rammer tool that pushed the round into the barrel. The sponge head was dipped in water and run down the barrel to quench any embers left over.

Lauberdiere continued:

“Other accidents might have also happened, always caused by the cannon. Many of our navy officers who wanted to witness this drill rented horses. They were usually poor horsemen and wanted to remove all doubt, as three or four were thrown on the ground with each cannon shot.”

It appears there was an audience for the October 8th battle as well as the one described in Goddard’s account of the one on October 2nd.

The diary goes on to describe another drill, this one on the 11th of October:

“Mr. The Count de Rochambeau had the same drill at the point of Stauder’s house on the 11th, just as on the eighth. It was not executed with enough precision or vivacity. It’s on when we are outside the lines and near the one giving orders that we can see the mistakes and know how important it is to have well-informed officers and experienced soldiers. The former understand the orders they receive more easily with experience. In the election, the latter are more prompt, often foresee the objectives and march with greater assurance.”

Lauberdiere’s diary gives an insight into the value of these drills.

“A skirmish is an image of a real battle when it is well conceived and it is also educational. The only real difference, I think, is saving the blood of a large number of brave men. Our general, then, could not make better use of the leisure time which the English gave or to which our small number reduced us, than to accustom his soldiers to the sound of the musket and the cannon to teach them to march without fear especially on the land where they would really fight if the enemy appeared.” (page 46)