July 9, 1764: The St. John Incident:

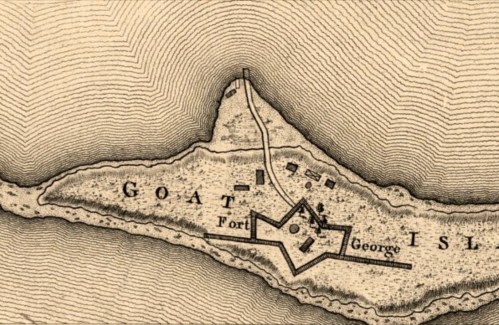

In 1763 the British sent warships to Newport to clamp down on smuggling. One such warship was the custom schooner St. John. The crew of the St. John had been accused of stealing livestock and threatening to impress local seamen (forcing men to serve on British ships). On July 9, 1764 the Rhode Island Governor (Stephen Hopkins) and General Assembly ordered the gunner at Fort George on Goat Island to fire at the St. John. Accounts vary, but from eight to thirteen shots were taken. The St. John hurriedly left Newport Harbor without sustaining much damage. Some Rhode Islanders consider these the first shots fired in the Revolution.

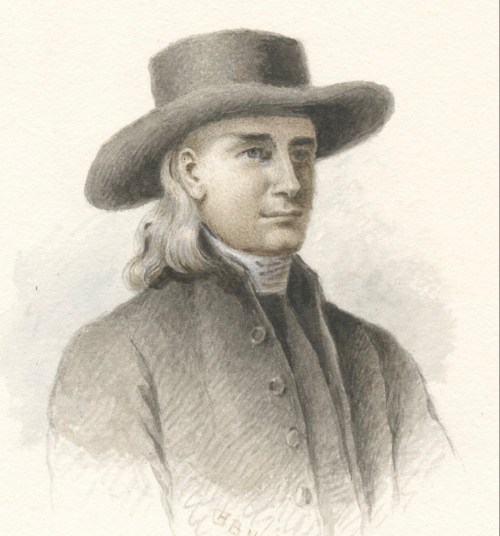

December 1764: Stephen Hopkins publishes Rights of Colonies Examined:

Hopkins was a key figure in Revolutionary Rhode Island. He was an early advocate for unity of the colonies and governor of the colony four times. He wrote the “Rights of Colonies Examined” in 1764 in response to the Stamp Act. Hopkins wrote that British subjects in America had equal rights with those in Britain. Taxes like the Stamp Act, which were passed “without their own consent”, had alarmed the colonists.

June 4, 1765: The Maidstone Incident

June 4, 1765 the HMS Maidstone with Captain Charles Antrobus commanding, was on customs duty in Narragansett Bay. The Maidstone’s Captain had impressed so many sailors that it effected the trade in Newport. A mob took the longboat from the ship and burned it in a town square

August 26, 1765: Stamp Act Riots in Newport begin.

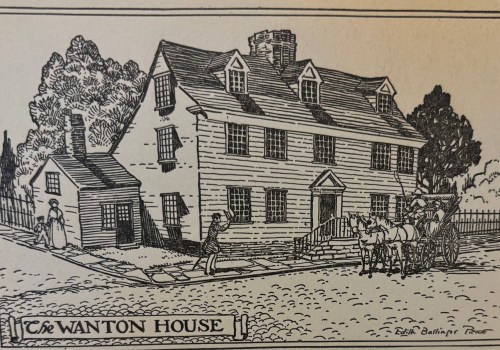

August 26. 1765 a gallows was erected in Queen Anne Square. Effigies (dummies) of the three Stamp Act defenders (Martin Howard, Dr. Moffat and Stamp Master Johnson) had been created and hung in the gallows. These were guarded by William Ellery (who would sign the Declaration of Independence), Samuel Vernon and Robert Crook. These men may have been leaders in the Sons of Liberty. A mob collected and after sundown the effigies were burned. Wanton, Lyman, Hazard House (Now owned by the Newport Historical Society) was the Howard House at the time of the Stamp Act. At 8 in the evening the ring leaders and a band of ruffians carrying axes and other tools, invaded Howard’s house. They demolished china, furniture, clothing and linens. They carried away his wines and liquors. They went back at 11 PM and destroyed most of the house before they headed to Dr. Moffat’s house which they also ruined. The three Stamp Act defenders had sought safety onboard the Man of War in the harbor. The crowd then surrounded the house of Stamp-Master Johnson, but since he had promised to resign his office, they didn’t carry out any destruction. Howard and Dr. Moffat took a ship to England by the first of September. Newport riots were the most violent in the colonies.

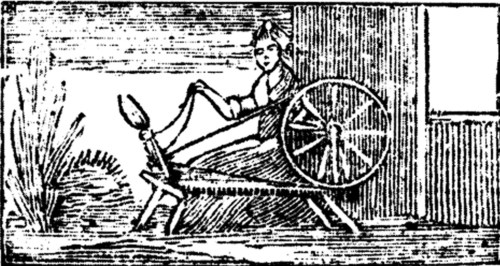

March 4, 1766: Daughters of Liberty established in Newport – first in the colonies.

In Newport the stamp tax was met with some violence, but the women took more peaceful strategies. The women hoped that if Americans boycotted English goods that British merchants would pressure Parliament to repeal the Act. Colonial women had the responsibility of purchasing and making goods their families needed. They were willing to make the sacrifices needed to make a political statement. It gave women a voice at a time when they couldn’t hold public office. Benjamin Franklin appeared before the British House of Commons to argue against the Stamp Act. He noted that while Americans used to take pride in wearing fine imported garments, it was now their pride “to wear their old clothes over again, til they can make new ones.” As a protest, women gathered to spin their own cloth instead of buying yarn and fabric from Great Britain. Reports of these spinning bees were mentioned in newspapers and the bees were located throughout Rhode Island. Ninety-two women gathered in Newport. The elite class of women were not used to spinning and there was a report of a seventy year old women learning to spin for the protest. The women spent the day spinning and produced 170 skeins of yarn.

July 19, 1768: The Liberty Incident – Protests in Boston and Newport

On the 19th of July in 1769 a Newport mob was so exasperated with the captain of a sloop owned by Royal Commissioners that they “went on board the Liberty as she lay at Anchor in the Harbour, and cut her cables, and let her drift ashore, they then set her on fire…” (Boston Chronicles, 24, July 1769). This incident was almost three years before the burning of the Gaspee.

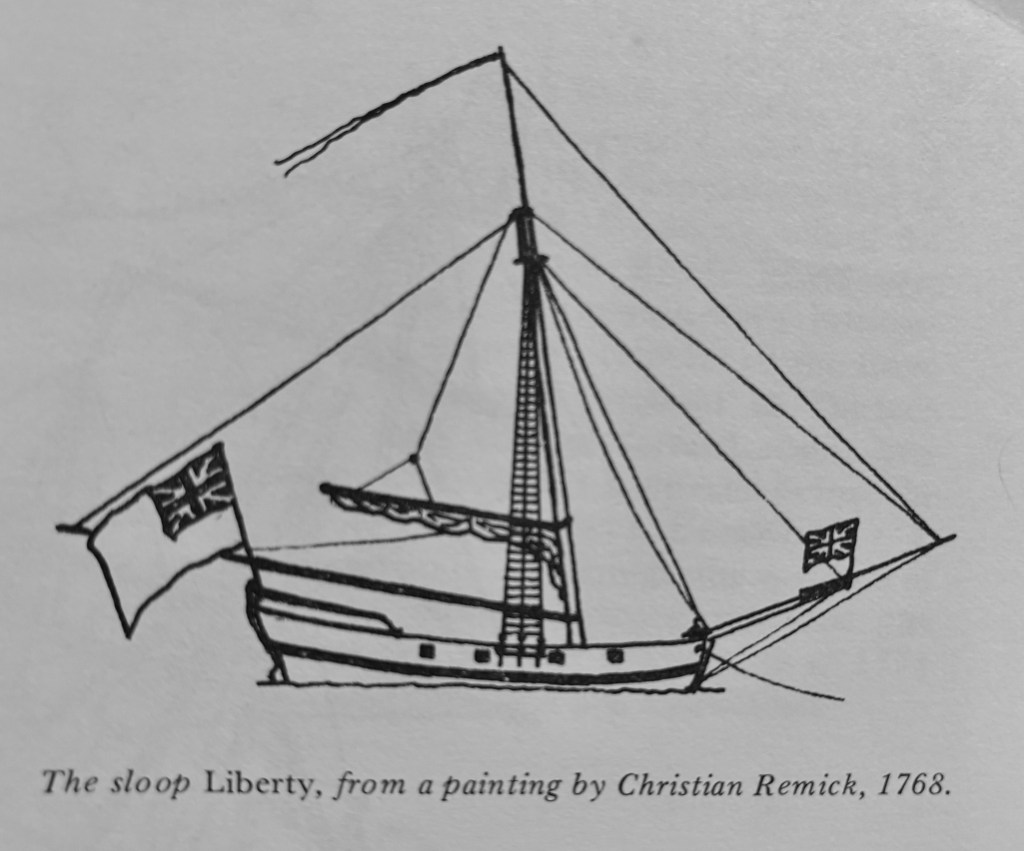

Liberty’s story begins in Boston.

The Revenue Act of 1767, part of the Townshend Acts, placed heavy taxes on goods imported to the colony. The American Board of Customs Commissioners was put in place so that royal officials could inspect incoming merchant vessels and charge the appropriate taxes, but Hancock had refused to allow the officials to inspect one of his vessels – the Lydia. When the customs official was sent to inspect the Liberty, he accused Hancock’s men of offering him a bribe to look the other way while they were unloading. He refused the bribe and he claimed they locked him in the hold of the ship. When news of the incident spread, an angry crowd assaulted the officials involved, broke the windows of their homes and set the officials’ personal boats on fire on the Commons. The sloop was seized at Boston Harbor on June 10, 1768. John Adams defended Hancock against the smuggling charges. The case dragged on and the charges were later dropped due to lack of evidence. The sloop Liberty, however, had been seized and Hancock could not get it back. It was condemned in August of 1768 and sold in September.

Newport: The Burning of the Sloop Liberty

Parliament’s taxation laws hit the New England economy hard, and some turned to smuggling to avoid the taxes. In 1769 the sloop Liberty came into Newport Harbor. It was the same sloop that had been seized from John Hancock. The captain, William Reid, was authorized to capture smugglers and in return he and his crew would receive a bounty. The Liberty was a private vessel hired by the Commissioners of Customs. Reid had the reputation for being overly zealous in carrying out his orders. He frequently boarded and searched legitimate merchant ships and delayed their sailing. On 17 July 1769 the Liberty took a Connecticut-owned brig into custody on Long Island Sound and brought her to Newport. But Reid could not prove the brig had violated any laws. Captain Packwood, the ship’s master, had declared his cargo at the customs house before sailing. Reid’s crew continued to hold the ship in the hopes something else would be discovered to justify their bounty for the capture. Captain Packwood visited the Liberty to take control of his vessel, but shots were fired towards him. Local Newporters became outraged and a crowd gathered. Tempers flared when local officials would not help the Captain get his vessel back. A group of men attacked the Liberty, cutting the sloop’s mooring lines and drifting her down toward Long Wharf. One report is that they cut down her masts and threw her guns overboard. The hulk drifted out of the harbor on the tide and came to rest on Goat Island, where another mob set her ablaze. The burning of the barge and the boat the accompanied the Liberty are commemorated with a plaque in Newport today.