When and where was the first naval battle of the American Revolution? You might not be surprised to know that battle took place off of Newport. The date was the 15th of June in 1775, not long after the Colonial General Assembly enacted a resolution to charter and arm two vessels for the protection of trade on June 12, 1775.

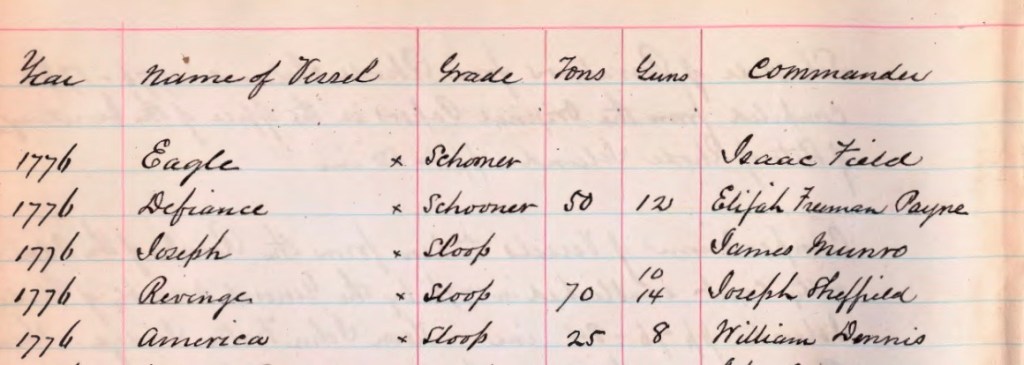

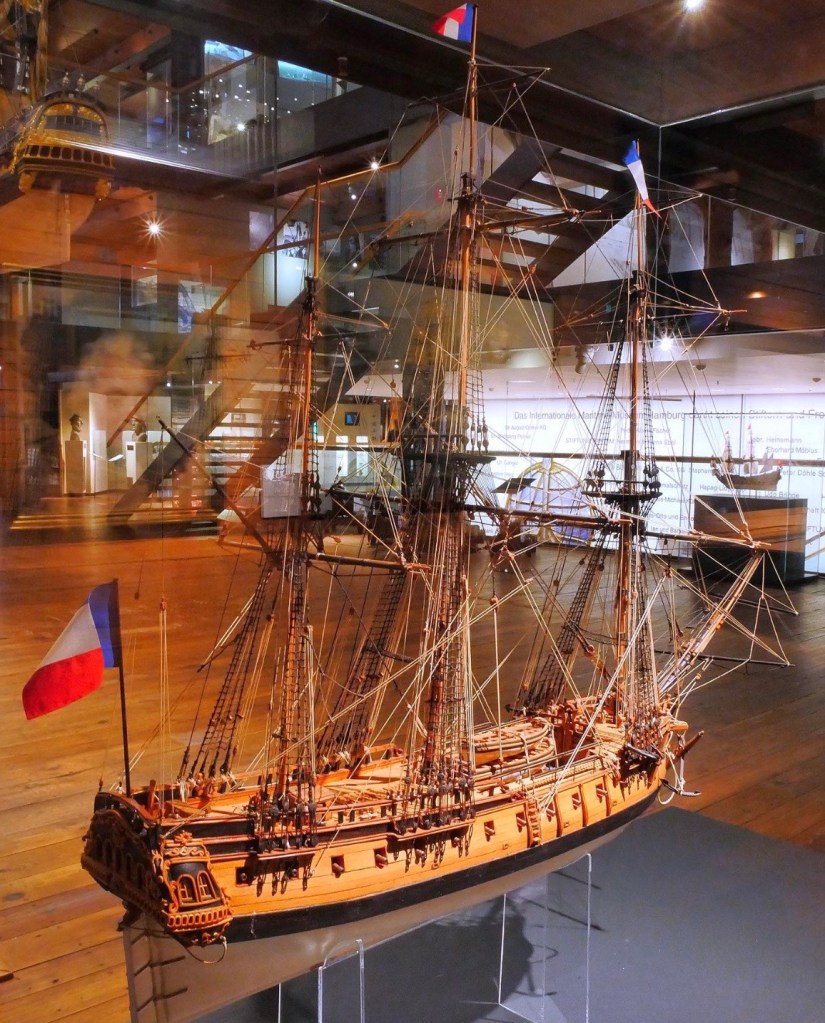

In 1774, the British frigate, the Rose, under the command of Sir James Wallace, was sent to Narragansett Bay in Rhode Island. The Rose was successful in ending the smuggling that had made Newport wealthy. John Brown and other leading merchants advocated for the protection of Rhode Island trade. The Rhode Island Assembly directed the committee of safety to charter two vessels for protection. This action created the Rhode Island Navy, the first American Navy of the Revolution.

Merchant Brown chartered one of his sloops, the Katy, to this new Navy. Abraham Whipple, one of Brown’s best captains, assumed command of the Katy and a smaller vessel – the Washington. As the new commodore, Whipple lost no time in trying to clear the smaller ship tenders of the Rose from their positions in Narragansett Bay. Whipple had more fire power than the tenders and he was able to fire on the sloop Diana and take her as a prize on June 15, 1775. This was the first naval engagement of the Revolutionary War.

Whipple towed the Diana back to Providence and when the Rose sailed up the Bay to investigate what happened to the Diana, Newport citizens were able to recapture five out of the six Newport merchant ships that Wallace had confiscated.

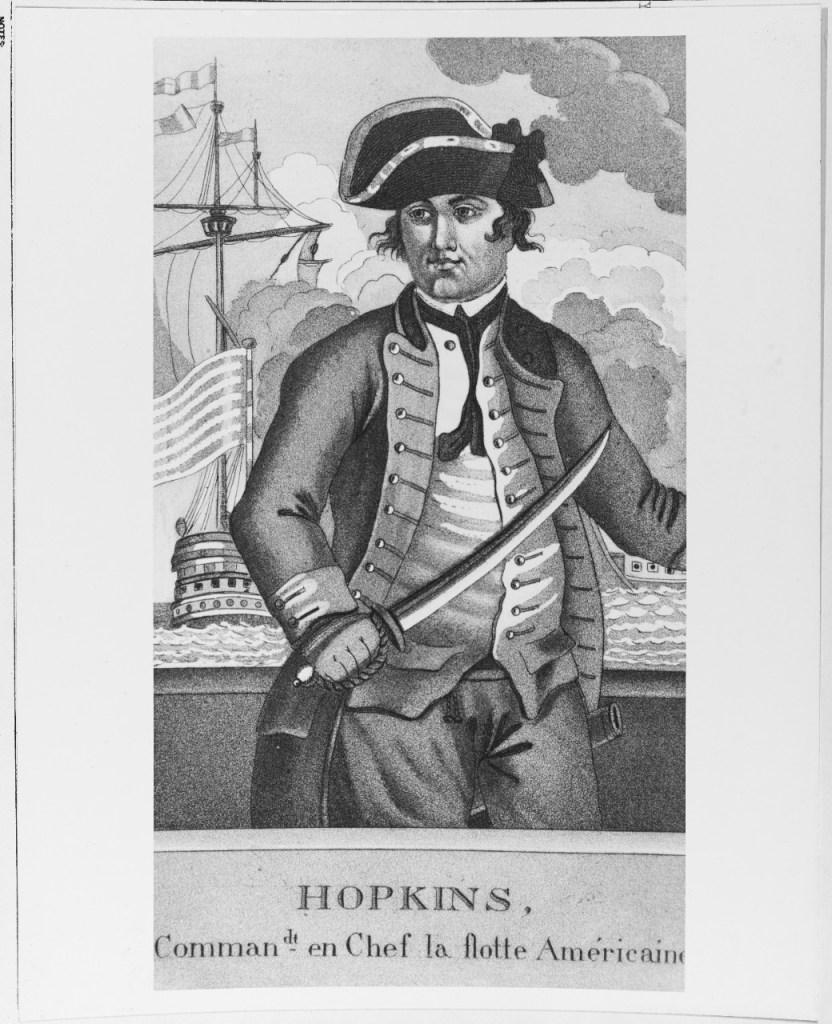

The new Rhode Island Navy was not powerful enough to take on the British frigate Rose, so the Rhode Island Assembly instructed their delegate to Congress, Stephen Hopkins, to introduce a bill to create the national navy. Congress passed the bill on Octber 13, 1775. The Katy (owned by John Brown) became the first ship of the Continental Navy and was renamed the Providence.