I collect eyewitness accounts of the Battle of Rhode Island. As I searched through my own local history collection, I came across an account I don’t remember reading. It is a transcription by John Millar of the diary of a Peter Reina, a young British soldier in the Battle of Rhode Island. Millar transcribed the diary from photocopies sent to him by an English descendent of Peter and the transcription appeared in the August, 1979 edition of the Rhode Island History Magazine.

Although the transcription begins with the arrival of the French fleet, I am going to share just the portion on the Battle of Rhode Island. It is interesting to have another British view to contrast the American diaries, Order Books and letters we have for research.

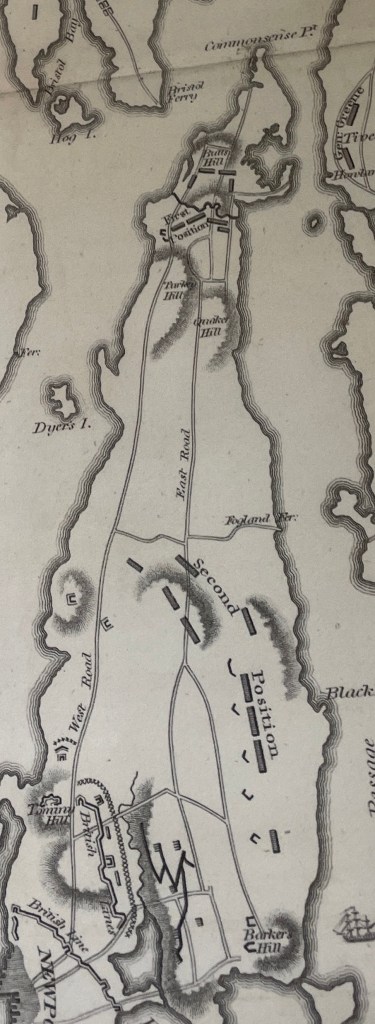

“Reports arriving by deserters: the enemy were retreating to the north end of the Island. The Commander in Chief, Sir Robert Pigot, on the morning of the 29th ordered the Light Infantry and Grenadiers with Brown’s and Fanning’s Corps to march out of their lines and attack them, as were the 22nd, 43rd with the Hessian and Anspach Corps from Easton’s Beach.

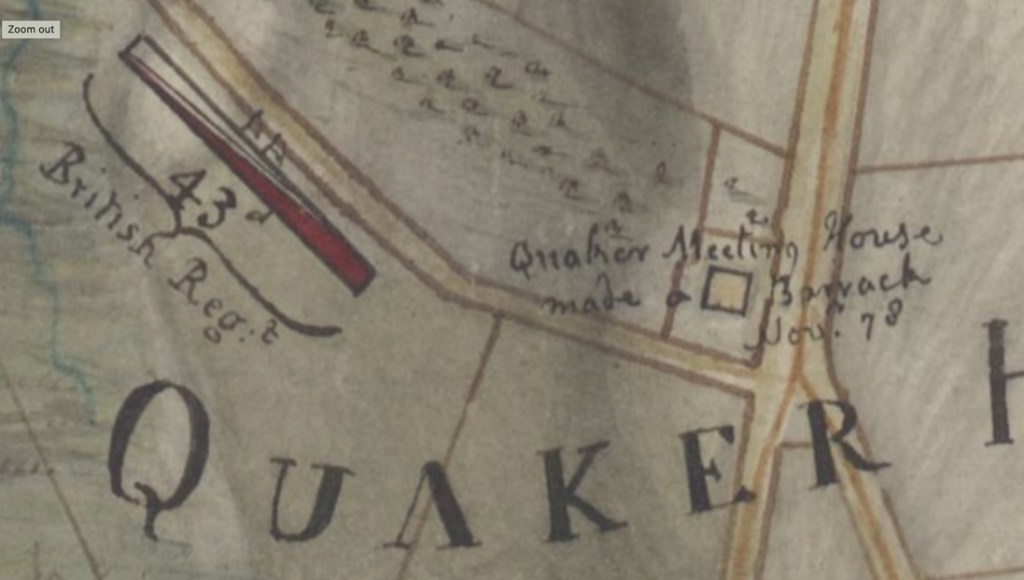

They marched without opposition for some miles till meeting with a considerable body of the enemy on Quaker Hill. A severe fire took place; the van of our small army, for some time being not supported by the rear, suffered considerably, but the foreign troops advancing to support of the 22nd and 43rd, the Rebels were repulsed and drove from their works with considerable slaughter on their part. They then took post on Windmill Hill, an eminence commanding every other and very strongly defended.

Our troops took post on Quaker’s Hill. Great numbers of wounded coming into the Town gave the Rebels there no small satisfaction; their countenances shew’d it while they at the same time seek’d to administer relief.

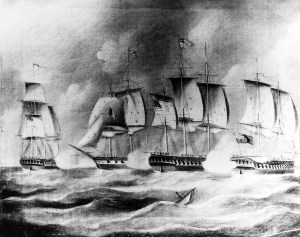

The Sphynx 20 gun ship and Vigilante galley which arrived on the 27th, were sent up the River to cut off the retreat of the Rebels, but they could not effect it, not getting past the batteries at Bristol Ferry.

However, the Rebels being quite dispirited by the loss of their Allies, they could not remain longer, and on the night of Sunday 30th totally evacuated the Island to our great satisfaction and ease.

Thus ended Mr. Sullivan’s third expedition on Rhode island, much to his dishonor and disgrace to his magnanimous allies, who with 25,000 men and a fleet of 12 ships of the line made a shameful retreat from before a small army not exceeding 6000 troops, and those but ill provided with artillery.”

Note: John FItzhugh Millar was very active in researching Rhode Island Revolutionary history in the timeframe of the bi-centennial.