Revolutionary Rhode Island Timeline Trifold

November 23, 2025

Portsmouth History Battle of Rhode Island, Revolutionary Rhode Island, Siege of Newport, Timelines Leave a comment

A Vistor’s Guide to Revolutionary Rhode Island

November 19, 2025

Portsmouth History Butts Hill Fort, Green End Fort, Greene Homestead, James Varnum, Patriots Park, Vernon House, Visitor's Guide Leave a comment

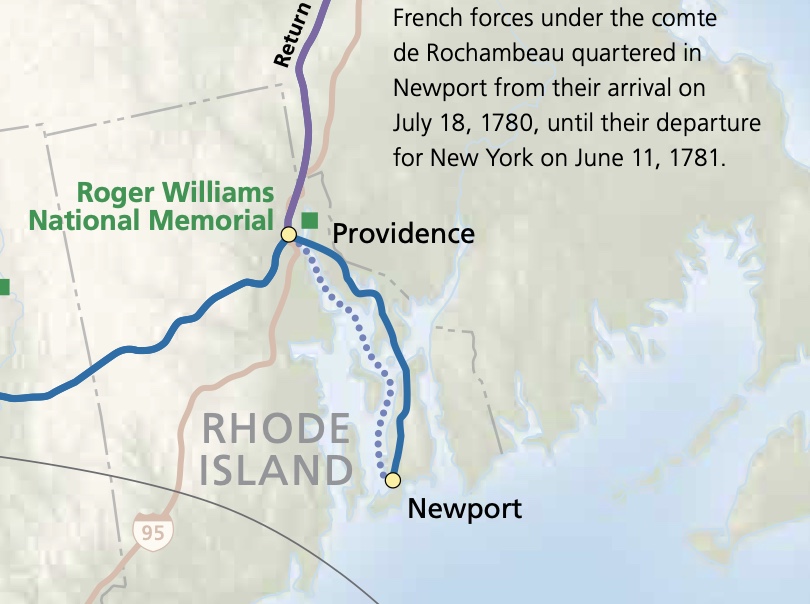

Rochambeau Trail Through Rhode Island

November 18, 2025

Portsmouth History French Army, Rochambeau, Washington - Rochambeau Trail Leave a comment

The French Arrive and Depart

The French arrived in Newport in July of 1780. Most of the forces wintered in Newport except the Lauzun Legion which camped in Connecticut. Rochambeau was very skillful in handling his troops and the Americans began to appreciate their presence. Where the British had demolished defenses, the French engineers worked on rebuilding them. Major General William Heath’s diary for September of 1780 notes that “The batteries were strengthened, a very strong one erected on Rose-Island, and redoubts on Coaster’s-Island: the strong works on Butt’s-Hill (were) pushed..” A few days later he would remark: “The French army continued very busy in fortifying Rhode-Island: some of their works were exceedingly strong, and mounted with heavy metal.” We know from orderly books (daily records) that the American militiamen were aiding the French masons as they enlarged and fortified Butts Hill Fort.

As the road to Yorktown began, Rochambeau and his general staff left Newport on June 10, 1781. He arrived at Providence the following day. Brigadier General de Choisy was left behind in Newport with some French troops. In August he sailed with Barras’ fleet to the Chesapeake area.

On the morning of June 11, 1781, the first Brigade of French troops began to load onto the small vessels in the harbor of Newport. All the troops had left by the 12th and camped on the west side of Providence between Westminster and Friendship streets. The French Army performed a grand review in Providence on June 16, then set out for Coventry in four divisions. One division departed each day from June 18 to 21. Rochambeau left Providence with the first division (the Bourbonnais Regiment) and arrived at Waterman Tavern in Coventry in the evening of June 18.

The Route:

- Followed the alignment of Broad Street to Olneyville.

- Passed through Stewart Street to High Street,

- West along High to the “junction” (Hoyle Tavern),

- Cranston Street (then called the Monkey Town road) to Route 14

- Route 14 to the eastern side of the Scituate Reservoir.

- The original road was lost to the reservoir but picks up again as Old Plainfield Pike in Scituate.

- West of Route 102 in Foster,

- Route 14 into Coventry.

There the army camped outside of Waterman’s Tavern.

General Rochambeau’s French Army was marching to join forces with General Washington’s Continental Army. The allied armies moved hundreds of miles toward victory in Yorktown, Virginia in September of 1781.

Resources

Washington – Rochambeau Trail: https://www.nps.gov/waro/learn/historyculture/washington-rochambeau-revolutionary-route.htm

Robert Selig article: https://digitalcommons.salve.edu/newporthistory/vol98/iss287/3/

Heroic Women on the Homefront

November 17, 2025

Portsmouth History Caty Greene, Daughters of Liberty, Katherine Wormsley Leave a comment

We naturally focus on the heroics of our soldiers, but often we don’t acknowledge the bravery of our women during wartime. Here are a few stories of Rhode Island women who courageously protested British taxes, capably did the their work and that of their soldier husbands, tended to soldiers in their camps, nursed hospitalized soldiers, committed to military service and risked themselves to manufacture armaments.

Daughters of Liberty

Colonial women had the responsibility of purchasing and making goods their families needed. In 1766 women made their protest to being taxed by the British by gathering to spin their own yarn and fabrics instead of buying them from Great Britain. Reports of these spinning bees were mentioned in newspapers and the bees were located throughout Rhode Island. Ninety-two women gathered in Newport. The elite class of women were not used to spinning and there was a report of a seventy year old women learning to spin for the protest. The women spent the day spinning and produced 170 skeins of yarn. Wearing homespun clothes instead of fancy fabrics from England was an effective and peaceful way to protest, but it also required courage for those who liveed in cities like Newport that had close ties to England. They were willing to make the sacrifices needed to make a political statement. It gave women a voice at a time when they couldn’t hold public office.

Women on the Home Front

“Keep the home fires burning” means to maintain a home’s daily routines and provide the necessities of life, often while someone is away. While their husbands were called to serve in the army, it was their wives that shouldered the extra burdens of tending to a farm or business. After the war the government gave a small amount of money to those who served in the Revolutionary War and we have records of the work some of these wives had to do. Dorcas Matteson of Coventry was the mother of nineteen children. She was married in 1770 to David Matteson. In the pension application she made years after the war, she listed some of the difficulties she endured for the “glorious cause.” When her husband went to fight in General Sullivan’s Rhode Island Campaign in 1778, it was hay time. She had to cradle her baby on some hay in a shady spot in the meadow while a young lad helped her load hay and put it in a barn. She was close enough to hear the “roar of the cannon” during the Battle of Rhode Island and she imagined the danger her husband was in. He returned a few days later when his militia duty had expired. He was safe and sound, but he did have a “bullet hole about him” that was made as they retreated from the Island. The bullet was stopped from injuring her husband by a chunk of cheese that Dorcas had sent and David had placed in his backpack.

A Special Camp Follower

Caty Greene was married to Nathanael Greene in 1774 and found herself quickly involved in the Revolutionary War effort. Nathanael moved quickly from commander of the Rhode Island Militia to general in the Continental Army. She opened her home in Coventry as a hospital when the Rhode Island troops were inoculated for small pox. Caty traveled to wherever her husband was stationed (New York City, Valley Forge, Carolinas), even after the birth of their first child in 1776. There were women and children who were called “camp followers” who served as cooks or clothes washers. Caty had more comfortable quarters than they did, and she put her efforts into organizing events for the soldiers. She became friends with Martha Washington because they were often in camp together. She gave birth to five children during the years of the Revolution, but when she travelled she often left her children in the care of others. Being away from her children and being away from her husband were heartaches for Caty. We don’t have the letters that Caty wrote to her husband because she burned them. We do have some of his letters to her and we can get a sense of what her letters were like from how he answered her. During the Siege of Newport, Nathanael wrote:

“I am sorry to find you are getting unwell. I am afraid it is the effect of anxiety and fearful apprehension. Remember the same good Providence protects all places, and secures from harm in the most perilous situation. Would to God it was in my power to give peace to your bosom, which I fear, is like a troubled ocean….” Caty, like many other spouses of Americans in the Rhode Island Campaign, must have been fearful of the battle ahead.

Civil War Nurse.

Nursing the injured is one important and heroic role that women have played though the years. Back in the Civil War days (1860s), nursing was not really a formal job with training. Women volunteered to help and learned to care for patients on the job. In 1862 Katherine Wormsley was living in Newport and was asked to be the head nurse at Lovell Hospital here in Portsmouth. She brought with her a staff of all women to supervise nurses who cared for patients in this 1700 bed hospital. Up until this time the supervisors had been all men. Katherine moved quickly and efficiently to set up round the clock schedules for proper care of patients. She asked for repairs to holes in the walls and appealed to towns like Portsmouth, Middletown and Newport for food and goods for the wounded soldiers. Her service lasted only a year, but those who worked with her describe her as being “clever, spirited, and energetic.” I would add heroic. Caring for wounded soldiers was a difficult task.

Mary Lopes, a Portsmouth woman who answered the call.

The Naval Reserve Act of 1916 permitted qualified “persons” for service and the Secretary of the Navy began enlisting women as “Yeoman (F).” Over 11,000 women answered the call. They served in a variety of jobs: clerical, bookkeeping, inventory control, telephone operators, radio operators, pharmacists, photographers, torpedo assemblers and other positions. The women did not go to boot camp, but they were in uniform. They had some of the same responsibilities and benefits as the men. Like the men they earned about $28 a month. They were treated as veterans after the war.

What do we know about Mary? Her parents were Manuel Lopes and Georgina Lopes. Their farm seemed to be on Middle Road close to School House Lane but there are listings for East Main Road also. The town directory of 1919 lists her as a “Yeowoman” in the United States Navy and living at home.

After the war the women were quickly released from service, but Mary stayed very active in the Portsmouth Post 18 of the American Legion. She was later Post Commander of the Rhode Island Women’s American Legion Post. Mary even returned to service as a nurses’ aide with the American Red Cross during World War II.

Our “Rosie the Riveters”

In 1943, Secretary of War Henry L. Stimson said “The War Department must fully utilize, immediately and effectively, the largest and potentially single source of labor available today—the vast reserve of women power.” At the Naval Torpedo Station in Newport women worked hard and long hours manufacturing torpedoes. At the Station, women worked in the Supply, Machine, Chemical, Personnel, Engineering, Design and Materials Departments. Newport resident, Isabella McNulty, was regularly exposed to poisons while she loaded equipment which screwed into the base of the torpedo shell. The building she worked in was incredibly loud and the powder she handled was poisonous. The women in this department did not wear gloves, because the parts they handled were so small that a gloved hand did not have the precision needed for the task. These were heroic women.

Women in the military today can serve in combat and non-combat roles. They can serve as pilots, mechanics, and infantry officers. Women continue brave service in support of the nation.

Getting Ready for War: Rhode Island Military Units

November 11, 2025

Portsmouth History Bristol Train of Artillery, Kentish Guards, Kingston Reds, Militia, Pawtuxet Rangers Leave a comment

As the threat of war intensified, the Rhode Island General Assembly passed a resolution on October 29, 1774 which listed militia forces which were to enlist men to fight against Crown forces. The Assembly had already ordered monthly militia drills and war preparations. The colony was actively organizing its militias in case of armed conflict.

Among the independent companies were the Kingston Reds, Pawtuxet Rangers, Gloucester Light Infantry, Providence Fusiliers, Providence, train of Artillery, and more. Earlier, in September, the Kentish Guards had received their charter. There was renewed interest in the traditional militias and independent companies were formed or renewed. Independent companies – Smithfield, Cumberland, North Providence, Wickford, Tiverton, Newport and Portsmouth were active. The Assembly had to create a committee to examine requests for establishing independent military companies. In Jan. 1775, these companies were grouped to form the R.I. 1st and 2nd Regiments, to answer the call of the Continental Congress which required two regiments in each colony.

Kentish Guards

On September 24, 1774 the Kentish Guards were formed to protect the Town of East Greenwich from British attack. They were then charted by the RI Assembly in October 1774 to be an “elite” militia which took care of its own training and equipment. The Kent County Court House became the armory and they built Fort Daniel at the entrance of Greenwich Cove and equipped it with nine cannons.

The Guards took part in the Siege of Boston and 35 of its officers ultimately became officers in the Continental Army – including Nathanael Greene. When the British invaded Newport, the Guards went on continuous duty until 1781. They protected Warwick Neck, Prudence Island, Warren, Bristol, Tiverton, and Aquidneck Island. As American forces congregated at Tiverton under General Sullivan, Kentish Guard commander Col. Richard Fry led a regiment of Independent Militia Companies at the Battle of Rhode Island. During the summer of 1779, twenty-six of the Kentish Guard attacked Conanicut Island (Jamestown) and destroyed a British battery. The Guard moved on to Aquidneck Island when the British evacuated Newport and they guarded Sachuest (Second Beach). They were posted at Newport again in 1780 and 1781 to reinforce the French.

Pawtuxet Rangers

The Pawtuxet Rangers (Second Independent Company for the County of Kent) were among those chartered by the Colony of Rhode Island and Providence Plantations on October 29, 1774. There were two types of military units during the Revolutionary War – independent chartered commands (like the Rangers) and Continental Regulars. In the years before the beginning of the War for Independence, busy seaports like Pawtuxet were at the heart of the economy. Rhode Islanders began to resent British actions such as the Sugar Act (1764), the Stamp Act (1765) and the Townsend Acts (1767). These acts stifled the maritime trade of towns like Pawtuxet. Some Rhode Islanders reacted with acts of defiance like the burning of the Gaspee in Pawtuxet in 1772. The Rangers first duties were to defend the bustling town of Pawtuxet, but they were expanded to include the construction and manning of a fort and the protection of 400 miles of the Rhode Island coastline from the Royal Navy.

With the British Occupation of Aquidneck Island (Rhode Island), the Rangers were kept busy. Besides guarding Pawtuxet, they were on duty on Prudence Island, Newport, East Greenwich, Bristol and Warwick Neck.

One pension request from a veteran Ranger states: “It was the duty of said company always to be in readings to march to whatever station it was commanded either by the Governor or the General of the Army having the command in Rhode Island. It also had the principal charge of a fort built in said village of Pawtuxet to repel incursions of the enemy which were very frequent during the time the British were in possession of Newport. While Rhode Island was in the theater of War, frequent & daring incursions were made all along the shores of Narragansett Bay by the enemy for the purpose of plunder and this Corps never failed to be among the foremost to repel them.”

Members of the Rangers served in the Battle of Rhode Island, the Battle of Saratoga and the Siege of Boston.

Kingston Reds

Like many of the ancient military units, the Kingston Reds were founded just before the start of the American Revolution. They were also created by an act of the Rhode Island Assembly in October 1775. Kingston was a wealthy port town at the time and the Kingston Reds were outfitted with uniforms of red coats, white shirts, white waistcoats, white breeches, long stockings, tricorn hats and dark buckled shoes.

They were part of the 3rd Kings County Regiment of Militia during the War for Independence. With other coastal militia groups, they shared the task of guarding Rhode Island’s long coast. They were active in battle at Little Rest Hill and the Battle of Rhode Island.

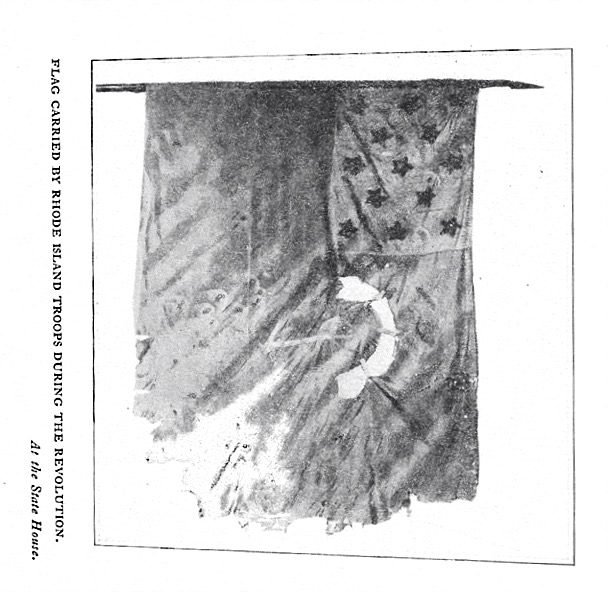

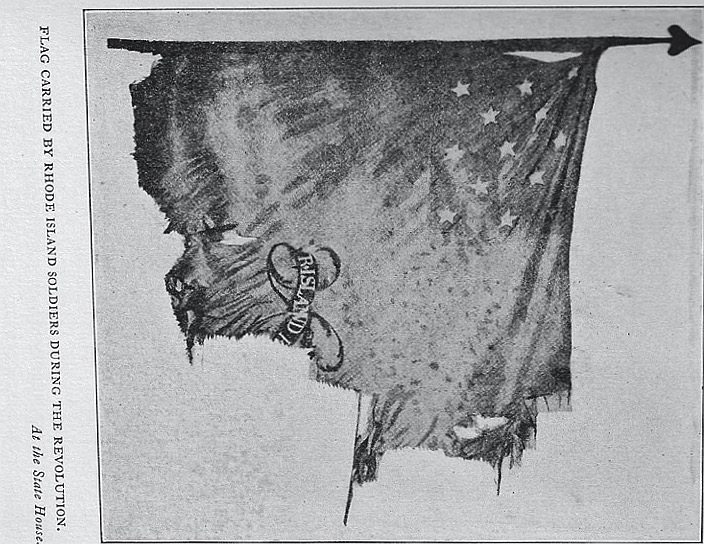

Rhode Islanders in the Wider War

November 11, 2025

Portsmouth History 1st Rhode Island Regiment, 2nd Rhode Island Regiment Flag, Continental Regiments Leave a comment

The Rhode Island Continental units began with an “Army of Observation” in 1775. In December of that year they were reenlisted under the Continental Congress. Militias were in the fight, too, but the Continental lines did most of the fighting throughout the war. The 1st and 2nd Regiments were merged into the Rhode Island Regiment in 1781.

Rhode Island Continental Line units

The list below is from the Rhode Island Historical Society

May 1775 Commissioned as Army of Observation by R.I. General Assembly, under the leadership of Brig. Gen. Nathanael Greene.

May 1775 Served in march to Prospect Hill in Boston

June 1775 Enlistments expired; reformed under continental service.

Dec. 1775 Church’s Third Regiment disbanded.

April 1776 Marched to Long Island

August 1776 Greene promoted to Major General; went to serve mostly in southern campaigns. Replaced by Brig. Gen. James M. Varnum.

Sept. 1776 Brigaded with the other two R.I. regiments under Richmond and Lippitt

Winter 1776-7 At Morristown, N.J.

Sept. 1777 Fought at Brandywine

Oct. 1777 Fought at Germantown and Fort Mercer / Red Bank

Nov. 1777 Fought at Fort Mifflin

12/77-6/78 At Valley Forge

6/78 Fought at Monmouth

1778 Varnum’s brigade under command of Maj. Gen. John Sullivan, in Rhode Island campaign.

Winter 1778-9 Camped for winter at Warren, R.I.

1779 Both regiments were in Rhode Island, in camp at Barber’s Heights, North Kingstown. after the retirement of Varnum, brigade under command of Brig. Gen. John Stark, with Maj. Gen. Horatio Gates

Oct. 1779 Transferred to Morristown, N.J.

Sept. 1780 Transfered to West Point, N.Y.

January 1781 Two regiments merged.

August 1781 Rhode Island continental regiment participated in crucial victory at Yorktown, Va. Capt. Stephen Olney’s company distinguished itself. After surrender of British Gen Cornwallis, fighting was virtually over.

Rhode Island Historical Society. https://www.rihs.org/mssinv/Mss673sg2.htm

The French in Newport: The Road to Yorktown Begins

November 10, 2025

Portsmouth History Butts Hill Fort, French in Newport, Rochambeau, Washington Leave a comment

October 25, 1779: The British evacuate Newport to consolidate their position in New York.

On July 11, 1780 a squadron of French warships approached Newport. It was not the first time the French came to Newport’s waters. The Treaty of Alliance with France was signed on February 6, 1778. On July 29, 1778 a French squadron sailed into Narragansett Bay. It created a military alliance between the United States and France against Great Britain. On the American side it was negotiated by Benjamin Franklin, Silas Deane, and Arthur Lee. This treaty stipulated that France and America would not negotiate a separate peace with Britain and that American independence would be a requirement before any peace treaty was signed. The Rhode Island Campaign in 1778 was the first French and American operation under the treaty. This joint action ended prematurely when damage from a storm took the French out of the Campaign.

In 1780 the “Expedition Particuliere” or Special Expedition would be a successful alliance. In July of 1781 Rochambeau’s French troops would leave Newport to join Washington’s army for the ultimate victory over the British in Yorktown.

The French arrived in Newport in July of 1780. Most of the forces wintered in Newport except the Lauzun Legion which camped in Connecticut. Rochambeau was very skillful in handling his troops and the Americans began to appreciate their presence. Where the British had demolished defenses, the French engineers worked on rebuilding them. Major General William Heath’s diary for September of 1780 notes that “The batteries were strengthened, a very strong one erected on Rose-Island, and redoubts on Coaster’s-Island: the strong works on Butt’s-Hill (were) pushed..” A few days later he would remark: “The French army continued very busy in fortifying Rhode-Island: some of their works were exceedingly strong, and mounted with heavy metal.” We know from orderly books (daily records) that the American militiamen were aiding the French masons as they enlarged and fortified Butts Hill Fort.

On March 6, 1781, three months before the French army departed from Newport, General Washington visited Count de Rochambeau to consult with him concerning the operation of the troops under his command. Washington was hoping to encourage Rochambeau to send out his fleet to attack New York City. In an address to the people of Newport, Washington expressed gratitude for the help of the French:

“The conduct of the French Army and fleet, of which the inhabitants testify so grateful and affectionate a sense, at the same time that it evinces the wisdom of the commanders and the discipline of the troops, is a new proof of the magnanimity of the nations. It is a further demonstration of that general zeal and concern for the happiness of America which brought them to our assistance; a happy presage of future harmony…appeasing evidence that an intercourse between the two nations will more and more cement the union by the solid and lasting times of mutual affection.” (Quote taken from New Materials for the History of the American Revolution by J. Durant. Henry Holt, New York, 1889.)

Washington left Newport and journeyed overland to Providence. On his departure he was saluted by the French with thirteen guns and again the troops were drawn up in line in his honor. Count de Rochambeau escorted Washington for some distance out of town, and Count Dumas with several other officers of the French army accompanied him to Providence. We know that General George Washington travelled by Butts Hill Fort on the old West Main Road on his way to the Bristol Ferry because the West Road was the customary route from Newport to the ferry. Washington’s aide, Tench Tilghman, recorded the fee for the Bristol Ferry on the expense book.

In May of 1781 Washington and Rochambeau met again, this time in Weathersfield, Connecticut. This meeting confirmed the joining of the forces and the march South.

The French left Newport in stages:

Regiment Bourbonnois under the vicomte de Rochambeau, left on June 18

Regiment Royal Deux-Ponts under the baron de Vioménil, left on June 19

Regiment Soissonnois under the comte de Vioménil, left on June 20

Regiment Saintonge under the comte de Custine, left on June 21.

Brigadier General de Choisy was left behind in Newport with some French troops. He sailed with Barras’ fleet to the Chesapeake area in August. In the summer of 1781, General Rochambeau’s French Army joined forces with General Washington’s Continental Army, With the French Navy in support, the allied armies moved hundreds of miles toward victory in Yorktown, Virginia in September of 1781.

Resources:

https://www.nps.gov/waro/learn/historyculture/washington-rochambeau-revolutionary-route.htm

By Robert Selig, PhD. for the Washington-Rochambeau Revolutionary Route Resource Study & Environmental Assessment, 2006.

https://digitalcommons.providence.edu/cgi/viewcontent.cgi?article=1018&context=ri_history. Visit of George Washington to Newport in 1781 – French E. Chadwick. 1913

Loughrey, Mary Ellen. France and Rhode Island, 1686-1800. New York, King’s Crown Press, 1944.

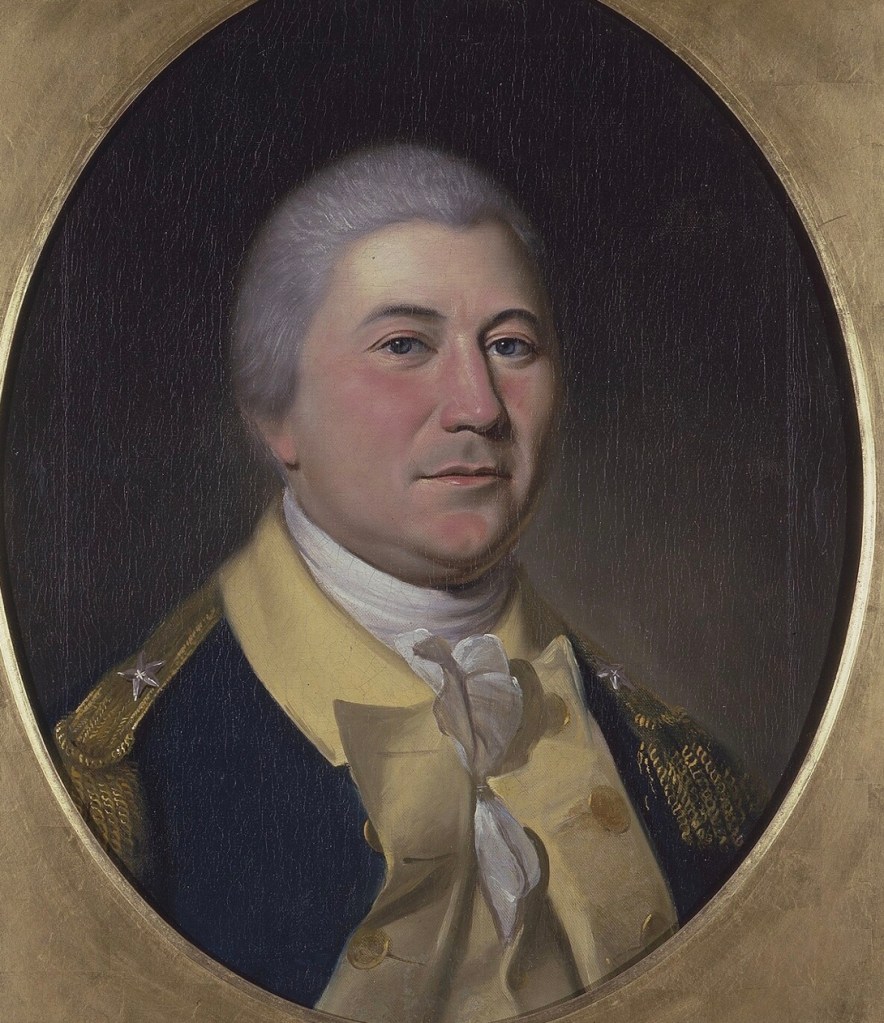

Rhode Island Commanders in the Battle of Rhode Island

November 8, 2025

Portsmouth History Battle of Rhode Island, Christopher Greene, Israel Angell, Nathanael Greene, Samuel Ward, Silas Talbot Leave a comment

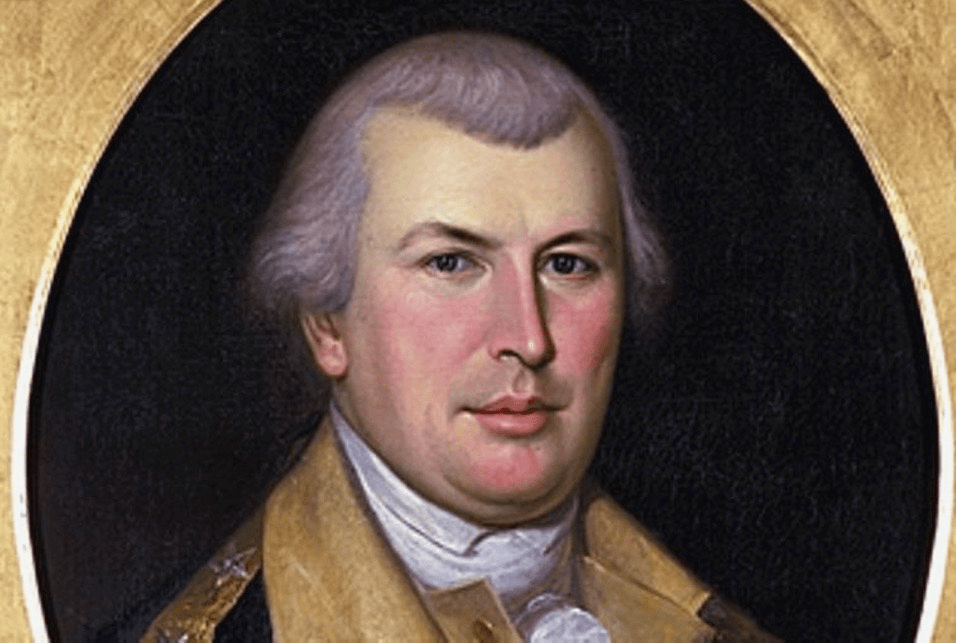

Major General Nathanael Greene: He was born into a Quaker family in the Coventry area of Rhode Island. Greene worked as the resident manager of the Coventry Iron Works, working at the forge making large ship anchors and chains until you enlisted in the army. Although of Quaker background, he was active early in the colonial fight against British revenue policies in the early 1770s. He was self educated and valued books and learning – especially about military topics. He helped establish the Kentish Guards, a state militia unit, but a limp prevented you from joining it. Rhode Island established an army after the April 1775 Battles of Lexington and Concord. Greene was tapped to command it. Later that year he became a general in the new Continental Army. He served under George Washington in the Boston campaign, the New York and New Jersey campaign, and the Philadelphia campaign. He was appointed quartermaster general of the Continental Army in 1778, but reserved the right to command troops in the field. Before the Battle of Rhode Island, he was placed in charge of the right flank of the army. He had the reputation of being one of Washington’s most talented Generals. In 1780 Washington put him in charge of the Army’s Southern Campaign and he fought through the end of the War.

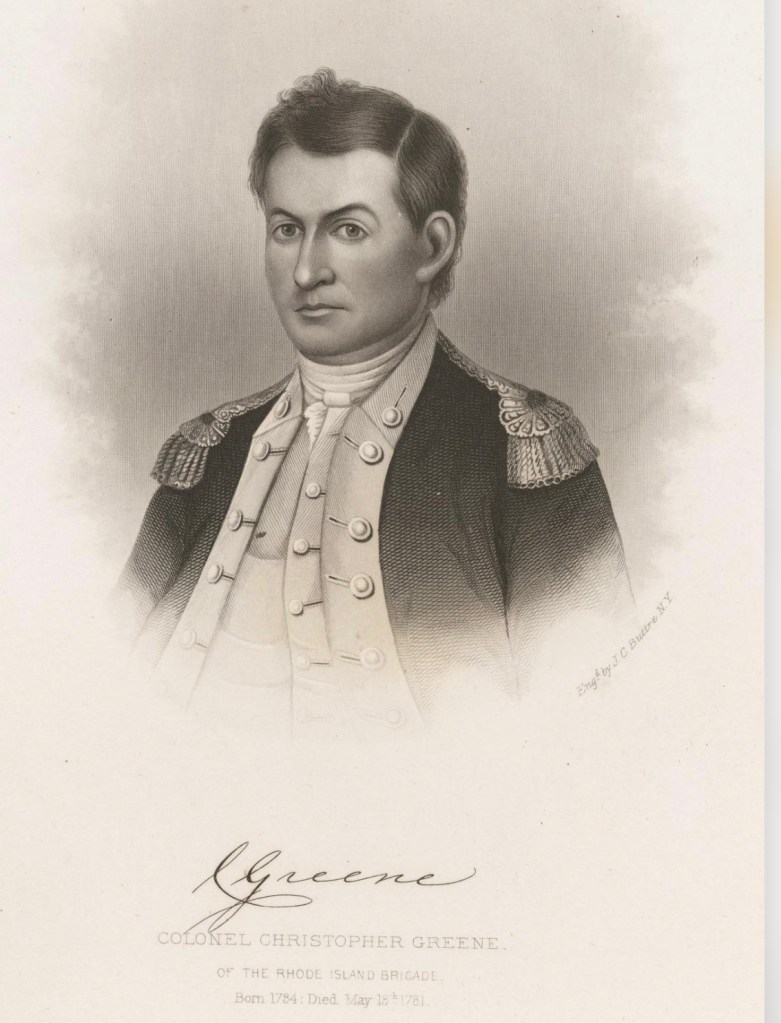

Col. Christopher Greene: He had long Rhode Island roots. He was a descendent of Rhode Island founder Roger Williams. Christopher Greene was a distant cousin of Nathanael Greene. Before the Revolutionary War, Christopher Greene served in the Rhode Island legislature from 1771 to 1772. With Nathanael he helped organize a militia unit, the Kentish Guards. After the Battles of Lexington and Concord he joined the army around Boston. He voluntarily joined Col. Benedict Arnold and was promotion to lieutenant colonel. He was with Arnold at the siege of Quebec and was was captured. He was released in August 1777 and joined the Continental Army for the Philadelphia Campaign. He was given command of the First Rhode Island Regiment. He defended Fort Mercer on the Delaware River. Washington agreed to enlist blacks and indigenous men to fill the ranks of a Rhode Island Regiment. The enlistments granted the soldiers their freedom if they served throughout the war. It benefited their owners with compensation. Christopher Greene was in charge recruiting, training and leading the 1st Rhode Island (the Black) Regiment. Colonel Greene died on May 14, 1781 at the hands of Loyalists by his headquarters on the Croton River in New York.

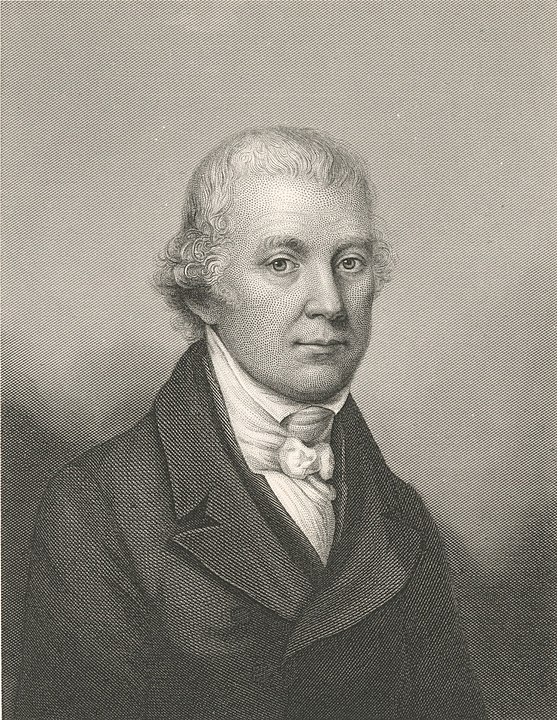

Col. Israel Angell: Angell came from one of the founding families of Providence. He served throughout the Revolutionary War. He was a major in Hitchcock’s Regiment at the beginning of the war and served with that regiment at the Siege of Boston. As the Continental Army was organized in 1776, Angell was part of the 11th Continental infantry. When Hitchcock was appointed brigade commander, he commanded the regiment. His regiment was re-named the 2nd Rhode Island Regiment on January 1, 1777. He was promoted to lieutenant colonel and shortly after to Colonel. He commanded the regiment following the death of Hitchcock. Angell was an experienced soldier who served at Valley Forge, the Siege of Boston, Brandywine, Red Bank, Monmouth and then the Battle of Rhode Island. At the Battle of Rhode Island he commanded 260 men. American General Nathanael Greene ordered Colonel Israel Angell’s 2nd Rhode Island Regiment to support Ward’s 1st Rhode Island Regiment. They were able to reach the key artillery redoubt before the British forces. He served in New York, but he retired from the army on January 1, 1781, after the two Rhode Island regiments were consolidated into a single regiment known as the Rhode Island Regiment.

Major Silas Talbot: He was born in Dighton, Massachusetts. He trained as a mariner and as a builder and made his home in Providence. In the aftermath of the burning of the Gaspee and the Boston Tea Party, Rhode Island merchants were alarmed. Independent militias were forming and he joined and was commissioned as a Lieutenant. He joined others in his company in learning military skills in a Providence warehouse, but he didn’t have any real military experience. On June 28, 1775 he answered the Rhode Island Assembly’s call to send units to Boston. He marched with his men to join the Second Rhode Island Regiment and by July 1, he was commissioned a captain. Talbot and the other 1200 men in the Rhode Island brigade took part in the Siege of Boston watching over the Red Coats but not in direct battle. His skills as a bricklayer came in handy as they built barracks on Prospect Hill. By April of 1776 the Siege was over and Rhode Islander Esek Hopkins, Commander in Chief of the Continental Navy, needed a crew to sail the ships home to Providence. Washington offered to loan Hopkins men from the Rhode Island Regiment and he switched from soldier to sailor. He was involved in the Rhode Island Campaign. As someone with experience as a mariner and builder, he helped to construct the flatboats that would take American forces to Portsmouth on August 9th of 1778. During the Battle of Rhode Island, Talbot led men in the early skirmishes on West Main Road. Talbot had success fighting on both land and sea. In 1779 he was made a Captain in the American Navy after he captured a British ship.

Major Samuel Ward: Ward was the son of a Rhode Island governor. His military career began when you were commissioned a captain in the Army of Observation in May, 1775, at the age of eighteen. He participated in Benedict Arnold’s attack on Quebec in December, 1775, under Lieutenant-Colonel Christopher Greene. He was taken prisoner by the British and released in August, 1776. He was promoted to the rank of major in the First Rhode Island Infantry and, between 1776 and 1778, served with his regiment at Morristown, New Jersey (1777); Peekskill, New York (1777); Red Bank (Fort Mercer) under Christopher Greene (1777); Valley Forge (1778); and the Battle of Rhode Island (1778). Ward retired from the Continental Army on January 1, 1781, when the 1st and 2nd Rhode Island Regiments were consolidated into the Rhode Island Regiment. Ward was the grandfather of Julia Ward Howe

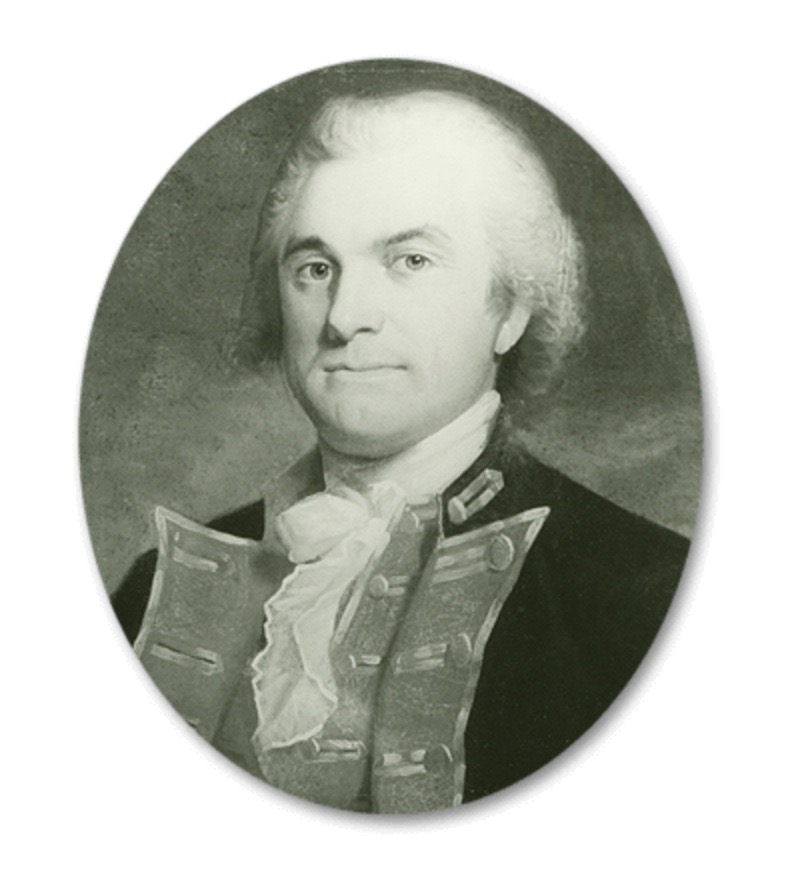

General James Mitchell Varnum: Varnum was born in Massachusetts but he came to Rhode Island to attend Brown. He married and set up a law practice in East Greenwich, and he independently studied military affairs. In October of 1774 he became a founder and commander of the Kentish Guards a imilitia company in East Greenwich, Rhode Island. With the fighting at Lexington and Concord, Varnum started to march his militia to Boston but they were not needed and headed home. In May 1775 Varnum was commissioned as a Colonel of the 1st Regiment of Rhode Island. By 1776 the regiment was folded into the Continental Army under the command of Brigadier General Nathanael Greene, Varnum’s friend. From Varnum and his Rhode Islander troops took part in participated major engagements including the Battle of Bunker Hill and the Battle of Rhode Island. Varnum and his men were at Valley Forge. Varnum was another proponent of raising a regiment of black and indigenous soldiers. In March 1779, he retired from the Continental forces and accepted a commission as Major General of the Rhode Island militia. Upon returning home to East Greenwich he was elected to the Continental Congress in 1780.

Rhode Island Campaign Timeline

November 7, 2025

Portsmouth History Battle of Rhode Island, Rhode Island Campaign Leave a comment

The Occupation of Aquidneck Island dragged on for almost two years when a plan was devised to work with French allies in pushing the British out of the island. On May 4, 1778 Congress ratified a treaty of alliance with France. The Rhode Island Campaign was devised as a wedge action. The Americans, under the leadership of John Sullivan, would cross from Tiverton to Portsmouth and drive south to set up a siege of Newport. Meanwhile the French, led by d’Estaing, would arrive by sea and attack the British from the sea.

Timeline for the Campaign

July 22, 1778, Washington informs Sullivan that the French fleet is headed to Newport, and he directs Sullivan to increase the size of his militia forces from 5000 to 7500.

July 27, 1778, Washington dispatches two Continental Army divisions under General Nathanael Greene and General Lafayette to Rhode Island.

July 29, 1778, French ships arrive at Narragansett Bay.

August 1, 1778, General Sullivan and Admiral d’Estaing meet, agree on simultaneous attacks on the Island on August 8.

August 6, 1778, Due to late arriving militia, Sullivan informs d’Estaing of postponement of the attack until August 10. A British Fleet under Admiral Sir Richard Howe leaves New York for Newport.

August 7-8, 1778, d’Estaing enters Narragansett Bay, causing British to withdraw from north end of the Island into prepared positions along the Newport-Middletown border.

August 9, 1778, Realizing the British had withdrawn south, Sullivan moves his forces onto the Island.

D’Estaing is alerted to the imminent arrival of Howe’s fleet.

August 10, 1778, French head out to sea. Both French and British fleets maneuver for advantage, but before they can engage, both fleets are scattered and damaged by a hurricane. Both leave for port and repairs.

August 11, 1778, General Sullivan prepares to invest British positions, but the hurricane causes him to delay.

August 15, 1778, Americans open the Siege of Newport.

August 20, 1778, d’Estaing’s battered ships return to Narragansett Bay. D’Estaing informs Sullivan he must immediately leave for Boston for repairs.

August 21, 1778, French fleet sails for Boston.

August 28, 1778, American council of war decides to withdraw Patriot forces from Rhode (Aquidneck) Island

August 29, 1778, Battle of Rhode Island is fought as Americans retreat northward.

August 30-31, 1778, overnight Sullivan’s army withdraws across the Sakonnet Straight to Tiverton with all its equipment.

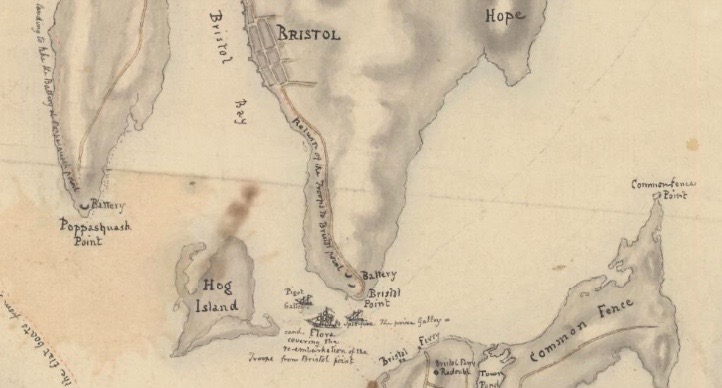

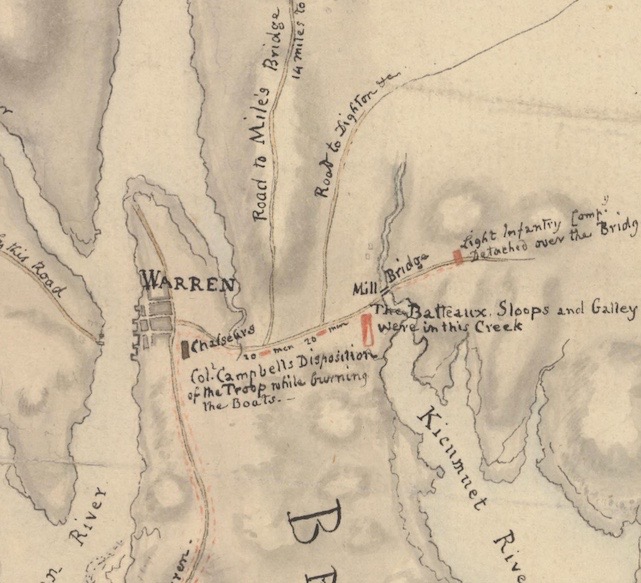

British Raids of Bristol and Warren: May 25, 1778 – Plus Other Raids

November 6, 2025

Portsmouth History Warren, Bristol, Campbell Leave a comment

As the American forces were preparing for an attack on Aquidneck Island in Spring of 1778, the British forces were active in trying to crush the Rebel capability to transport troops across the river from Tiverton. The Rebels would need to reach Rhode Island (Aquidneck) by boat and the British planned to attack shipyards, lumber mills and military stores. On May 25, 1778,British soldier Frederick Mackenzie records that the 22nd Regiment, Companies of the 54th, Notenius’s Company of Hessian Chasseurs, ..etc. (500 men in total) moved to Arnold’s Point in Portsmouth. They embarked in flatboats and landed at the mouth of the Warren River. Campbell’s men were divided into two columns. In the town of Warren itself they burned down the Baptist meeting house and other buildings, ransacked homes and property. The other group of Campbell’s men headed to the Kickemuit River. By the Kikemuit Bridge they found and burned 125 boats, large batteaux capable of carrying 40 soldiers. They found a sloop loaded with military stores, a store house, and a corn mill and they burned them. They also burned houses, a bridge and gun carriages. They spiked cannons and set fire to new Privateer Sloop as well as magazines of gun powder.

Campbells troops returned by way of Bristol. About 300 Rebels were assembled behind walls, trees and houses. They burned houses, a church, ammunition magazines and twenty of the principal houses. The British boats came round from Papasquash Point to the Bristol Ferry. The British ships Flora and Pigot covered the British troops as they crossed over from Bristol Ferry.

Having raided Warren and Bristol and destroying American flatboats, Campbell’s forces made their way back to Newport on their own flatboats.

The raids certainly delayed the American troops as they prepared for the Rhode Island Campaign.

Other Raids

August 24, 1775 British Captain Wallace landed around 100 men on Prudence Island. They sacked the farm of John Allin seizing sheep, turkeys, corn and hay. In November of 1775 they raided again and took clothing, geese, kettles and even a desk.

August 30, 1775 – Frigate Rose conducts raids on Block Island and Stonington, Conn.

Dec. 10, 1775 – Frigate Rose raids Jamestown

August 5, 1777 – British raid Narragansett

May 31, 1778 – British forces raid Tiverton and Fall River

May 21, 1779 – British raid North Kingston

June 6, 1779 – British raid Point Judith

October 16, 1779 – British burn Beavertail Lighthouse before leaving Rhode Island