When I speak to student groups I stress the hardships of Aquidneck Islanders during the British Occupation 1776-1779. Until I began to research Block Island in the Revolutionary era, I didn’t realize that they were suffering as well. The Rhode Island Assembly believed that leaving resources on Block Island might tempt the enemy to attack the island. Historian Reverend Livermore comments:

“The policy adopted was much like that of befriending a banker by taking away his money to save him from being robbed.”

Aquidneck Islanders had their livestock taken to feed the British army.

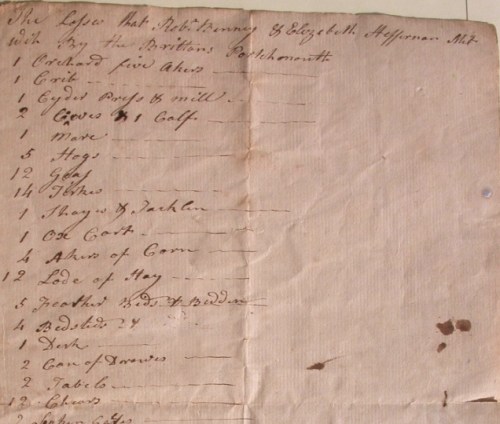

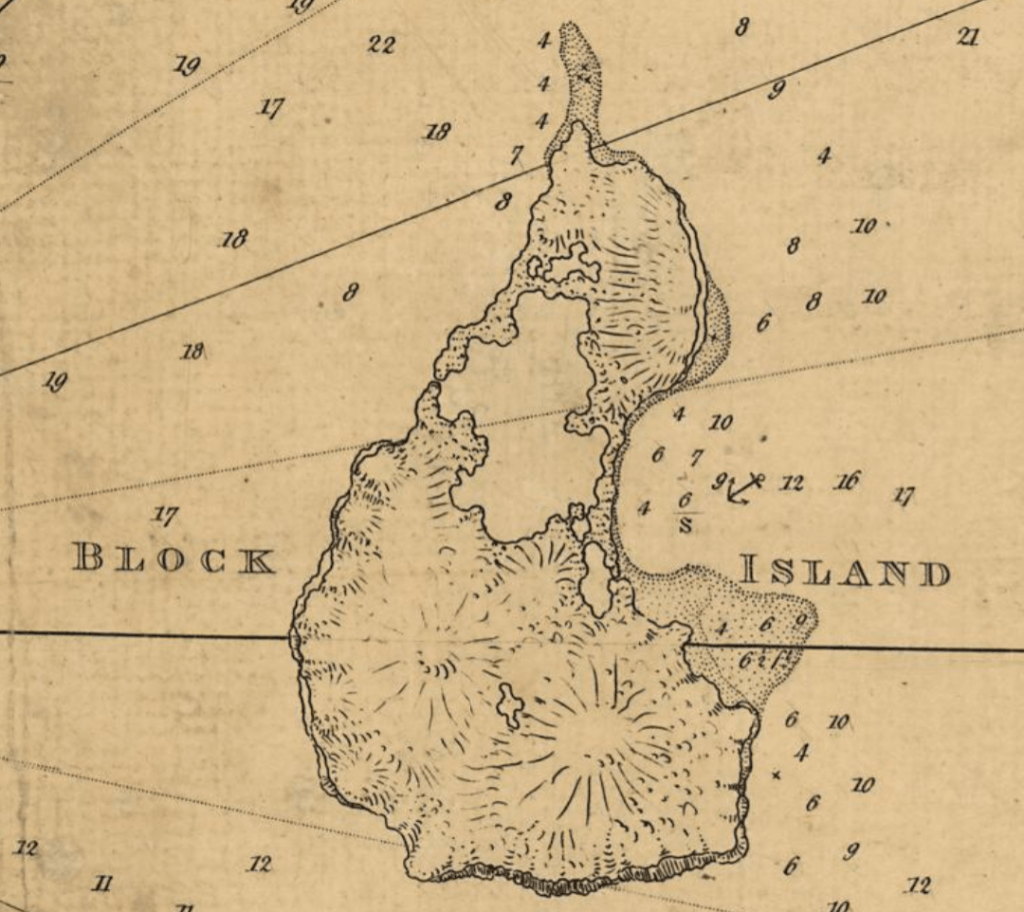

Block Islanders would find their livestock taken by the Rhode Island Colony. An act Passed by the General Assembly in August of 1775 directed that the the island livestock “be brought off as soon as possible, and landed upon the continent.” According to Block Island Historian Rev. Livermore: “Such stock as was suitable was to be sent immediately to the army. Such as was not fit for market was to be sold at public or private sale..” Almost 2,000 sheep and lambs were taken but there was no record how many cows and oxen. Captain John Sands, Joshua Sands, and William Littlefield were authorized to determine how much livestock was needed to feed the islanders. This same committee collected firearms and delivered them to the Rhode Island Committee of Safety. Then the went door to door and suggested that since the livestock was gone, Block Island men should volunteer for the American Army.

Aquidneck Islanders had no freedom of movement during the Occupation. They couldn’t get on or off the island or they would be suspected of spying.

The Colony of Rhode Island decided that Block Island residents were “in the power of the enemy” and therefore they could not leave the island.

“Whereas the inhabitants of New Shoreham, from their peculiar situation, are entirely in the power of the enemy, and very pernicious consequences may attend the intercourse of the said inhabitants with the continent, by means of the intelligence and supplies which the enemy may procure thereby:

” It is therefore voted and resolved, that the said inhabitants be, and they are hereby prohibited from coming from said Island into any other part of this State, upon pain of being considered as enemies to the State, and of being imprisoned in the jail in the county where they may be found, there to remain until they shall be discharged by the General Assembly…”

By the end of 1776 a committee (Sands, Sands and Littlefield) was given permission to gather needed supplies and bring them back to Block Island. In 1777 Block Islanders who were on the mainland were able to go back to the island.

Block Islanders were left under suspicion and without help from the mainland.

August of 1779: General Assembly

“Whereas, many evil minded persons, not regarding the ties of their allegiance to the United States in general, and this state in particular; but influenced by the sordid principles of avarice, continue illicitly to correspond with and supply the inhabitants of New Shoreham, in the county of Newport, with provisions, and other articles, to the great detriment and distress of the virtuous inhabitants of this state.”

“And whereas, the said town of New Shoreham hath been for a long time, and still is, within the power and jurisdiction of the enemies of the United States, whereby they obtain, in consequence of the evil practices aforesaid, supplies for themselves, and intelligence from time to time of the situation of our troops, posts, and shores; by which means they are enabled to make frequent incursions, and thereby commit devastations upon, and rob the innocent inhabitants of their property, and deprive them of their subsistence; wherefore, “Be it enacted, &etc.”

What this act did was to prohibit all trade with the islanders except by special permit. The offender’s property would be confiscated and he might have to do service in a continental battalion, or war vessel until the end of the war. Corporal punishment was the alternative if the offender was a female or unfit to be a soldier. There are records that some Block Islanders were treated as prisoners of war but their fates are unknown. By the end of 1779 the acts prohibiting Block Islanders from going to or from the mainland were abolished, but there were still restrictions on transport of goods. Even Governor Greene had to comply with these rules.

In July of 1780 messengers from the colony came to take whatever horses, cattle, grain, fish or cheese they deemed the Block Islanders could spare.

The Block Island historian Rev. Livermore wrote:

“Thus the Islanders, besides the depredations from the British, denied traffic on the main, unrepresented in the General Assembly of Rhode Island, unprotected by the colony from the enemy, was burdened with a heavy tax. This was taxation without representation; nay more, it was the imposition of a heavy burden upon those cut off from the common privileges on the main and abandoned to the cruel mercies of the enemy. But even this their faith and patriotism could endure while patiently waiting for the dawn of freedom.” (Livermore, pg. 102)

Livermore, S. T. A history of Block Island from its discovery, in , to the present time, 1876. Hartford, Conn., The Case, Lockwood & Brainard co, 1877. Pdf. https://www.loc.gov/item/rc01002999/.

Rhode Island., Bartlett, J. Russell. (185665). Records of the colony of Rhode Island and Providence plantations, in New England: Printed by order of the General assembly. Providence: A. C. Greene and brothers, state printers [etc.].

Finley, A, and Young & Delleker. Rhode Island

. [Philadelphia, 1829] Map. https://www.loc.gov/item/76692364/.