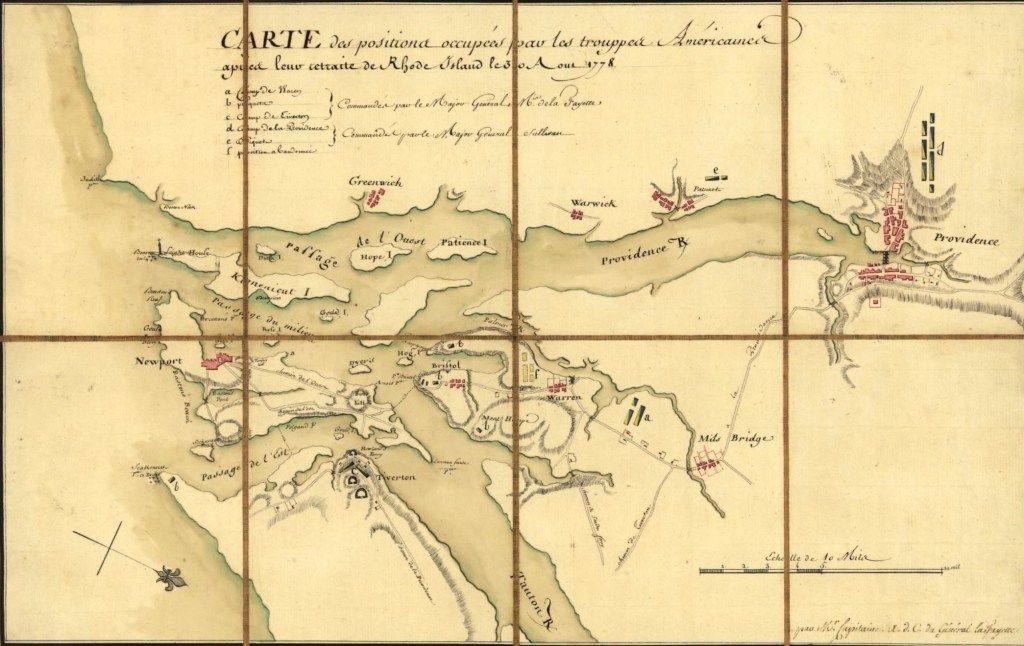

Last year at this time I published a blog on the “Daughters of Liberty”. Today I want to revisit the list of women associated with the Daughters. I have found that particular list in a few articles written around 1900 when chapters of the “Daughters of Liberty” were forming in various towns around Rhode Island. What I couldn’t find was any primary source confirmations of these women being involved in “Daughters of Liberty” – Mary Easton Wanton, Polly Wanton, Lucy Ellery, Patience Easton, Mary Champlin and Anne Vernon Olyphant. In searching for information on these women, I found these names and others listed in an Order of Cincinnatti in France 1905 book as giving hospitality to the French troops in Newport during 1780-1781. When I look at genealogical information on the women, I find that some were too young to participate in the 1766 spinning bees. The term “Daughter of Liberty” had been broadened to include patriotic women who furthered the cause for independence. Other sources list Martha Washington, Abigail Adams and Deborah Sampson (who actually fought as a man) as “Daughters of Liberty.”

Looking at primary sources, newspaper articles record the work of the Rhode Island “Daughters of Liberty” in protesting the Stamp Act and Townsend Act with boycotts of imported clothing. Most of the articles date from 1766. One of them is later, 1769.

An entry in The Boston Chronicle of April 7, 1766, states that on March 12, in Providence, Rhode Island, “18 Daughters of Liberty, young ladies of good reputation, assembled at the house of Doctor Ephraim Bowen, in this town. . . . There they exhibited a fine example of industry, by spinning from sunrise until dark, and displayed a spirit for saving their sinking country rarely to be found among persons of more age and experience.” At dinner, they “cheerfully agreed to omit tea, to render their conduct consistent. Besides this instance of their patriotism, before they separated, they unanimously resolved that the Stamp Act was unconstitutional, that they would purchase no more British manufactures unless it be repealed, and that they would not even admit the addresses of any gentlemen should they have the opportunity, without they determined to oppose its execution to the last extremity, if the occasion required.”

The Newport Mercury on April 14, 1766 included a letter to the editor that 20 young ladies met at the “invitation of some young Gentlemen of Liberty, and exhibited a most noble pattern of industry, from a quarter after sunrise til sunset, spinning 74 and 2/3 skeins of good Linen Yarn.” The toast was “Wheels and Flax, and a Fig for the Stamp Act and its Abettors.”

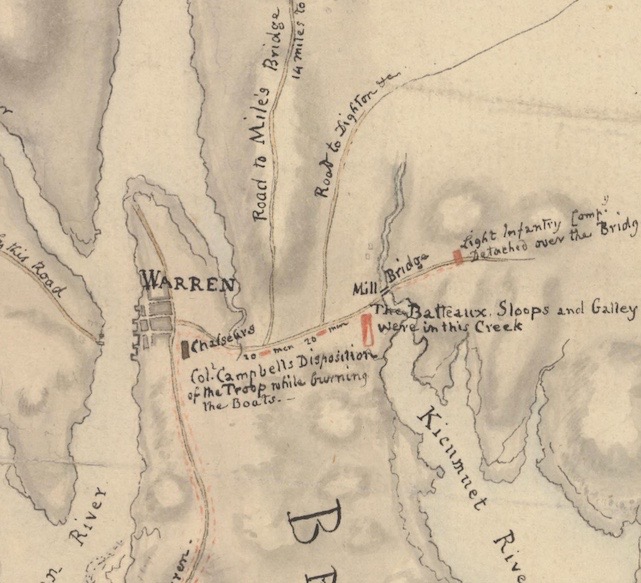

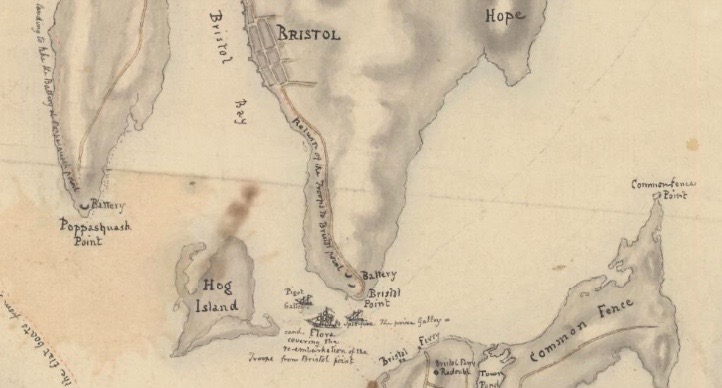

The Newport Mercury published a letter to the editor dated April 23, 1766. It detailed the results of two spinning matches held in Bristol on April 10th and 15th. A chart was attached with names and amounts of skeins spun. This is the only list of names I could find. I checked some of the names through genealogical sources and I could verify that many were Bristol girls and women.

New York Journal 24 August 1769: July 16. — Newport. July 10. “We can assure the Public, that Spinning is so much encouraged among us, that a Lady in Town, who is in very affluent Circumstances, and who is between 70 and 80 years of Age, has within about three Weeks become a very good Spinner, though she never spun a Thread in her Life before. Thus has the Love of Liberty and dread of Tyranny, kindled in the Breast of old and young, a glorious Flame, which will eminently distinguish the fair Sex of the present Time through far distant Ages.”

“Daughters of Liberty” seemed to be a term used for women who boycotted imported clothing, tea and other products. I can find mentions of the spinning bees in the period from 1766-1769. There was a patriotic organization of women’s groups around the country (circa 1900) which took the name “Daughters of Liberty.” They researched and promoted women who had been part of the Revolutionary War effort. In 1895 Alice Morse Earle wrote a book entitled Colonial Dames and Good Wives. She credits Rhode Island women with the beginning of the Daughters of Liberty.

“The earliest definite notice of any gathering of Daughters of Liberty was in Providence in 1766, when seventeen young ladies met at the house of Deacon Ephraim Bowen and spun all day long for the public benefit, and assumed the name Daughters of Liberty. The next meeting the little band had so increased in numbers that it had to meet in the Court House. At about the same time another band of daughters gathered at Newport, and an old list of the members has been preserved. It comprised all the beautiful and brilliant young girls for which Newport was at that time so celebrated.”[Pg 242].

I would love to see that “old list of the members.”