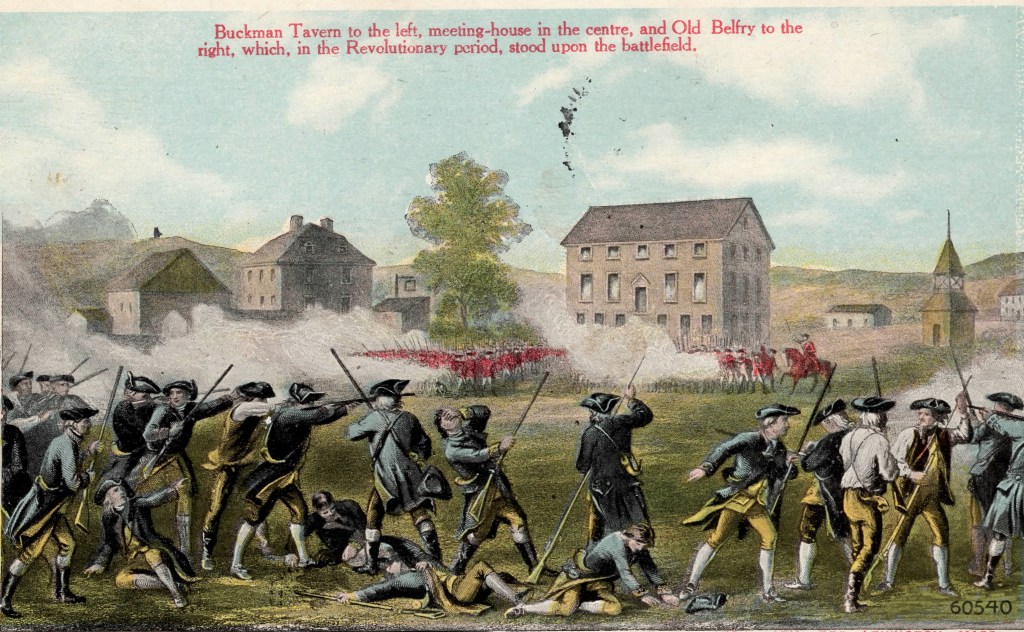

Tomorrow we honor those who participated in the Battle of Rhode Island with a Sunset Salute at Butts Hill Fort. Why did we have a battle? What was the spark? Over the past week I have heard an historian and a US Senator tell us that it was initiated by the British. I have been working on a role playing activity to let students and adults experience the decision making that principals in the Battle of Rhode Island had to make in the heat of the action. I like to draw from primary sources as I provide background material to the decisions that had to be made. Drawing from the diary of British soldier Frederick Mackenzie, I believe that the British were reacting to the retreat that they discovered that the Americans had already started overnight on August 28th.

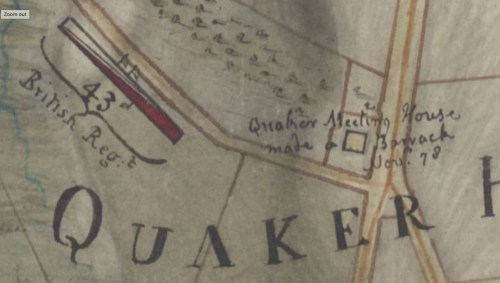

“As soon as the day broke this Morning and we could see as far as the Enemys Encampment it was observed that their tents were struck; I went immediately on top of Dudleys house, and when it grew lighter, I could plainly perceive that the Rebels had struck their whole Camp, and had marched off; hardly a man was to be seen in their Batteries or Trenches. I rode as fast as possible to General Pigot’s quarters in Newport and informed him of it, and returned to the Camp with his orders for all the troops to get under arms with the utmost expedition. The General came to Irishes Redoubt by the time the Troops were assembled, and being satisfied that the Rebels had quitted their position, he gave orders for a part of the Army to march out, in three Columns, to pursue them, but to advance with caution, and not bring on an Action with a part of our force.” Mackenzie’s diary August 29, 1778

The British didn’t decide to go on the attack against the American Siege of Newport. Mackenzie notes that the British were “to advance with caution, and not bring on an Action with a part of our force.” The British found that Americans had left their positions and General Pigot decided to go after them to capture the American Army before it could retreat off Aquidneck Island. The goal of the Americans was to get their soldiers and equipment safely to Tiverton so they could fight another day. The American aim in the battle was to push the British and German (Hessian) troops back so that a successful retreat could be made. They were in an untenable position once it was clear that the French were not coming back to aide in the plans of the Rhode Island Campaign. The Americans were not trying for a full engagement either.