October 25, 1779: British garrison evacuated Newport:

By 1779 strategic changes led the British to abandon Rhode Island of their own accord. Weary of trying to subdue the New England colonies, the British re-directed their efforts to the southern states where the population was thought to be overwhelmingly Loyalist. In addition, with France now firmly in the war on the side of the Americans, the British needed more ships and more soldiers in the West Indies to protect their interests in the Sugar Islands from the French. The money brought to the Crown from the islands far exceeded that from their North American colonies.

July 10, 1780: French Army under Rochambeau arrives in Newport:

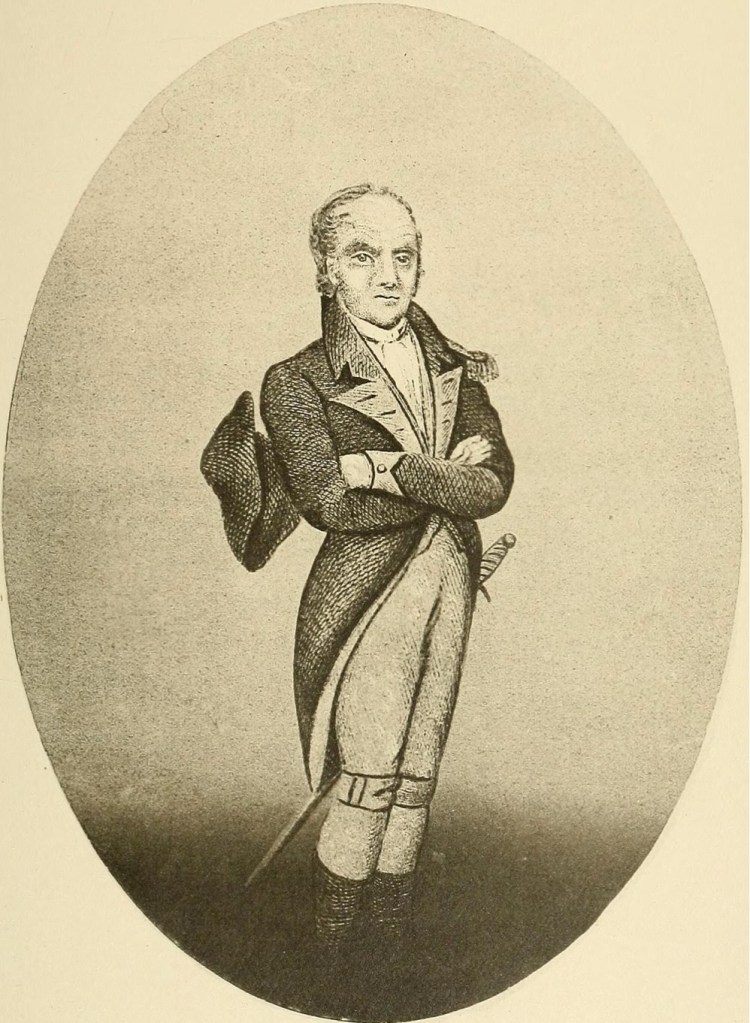

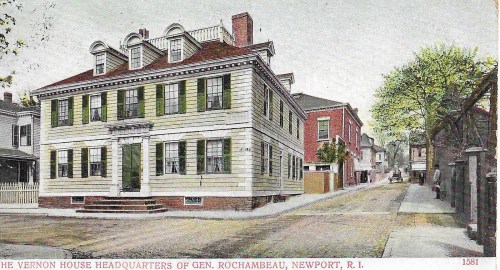

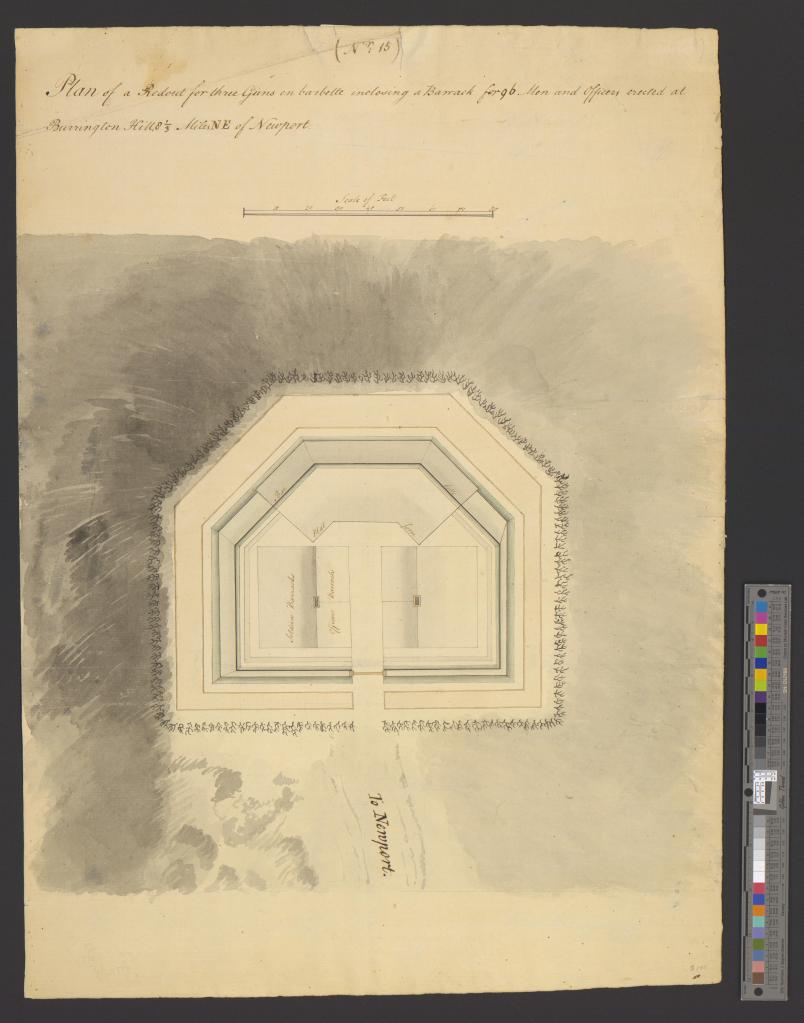

The French arrived in Newport in July of 1780. Most of the forces wintered in Newport except the Lauzun Legion which camped in Connecticut. Rochambeau was very skillful in handling his troops, and the Americans began to appreciate their presence. Where the British had demolished defenses, the French engineers worked on rebuilding them.

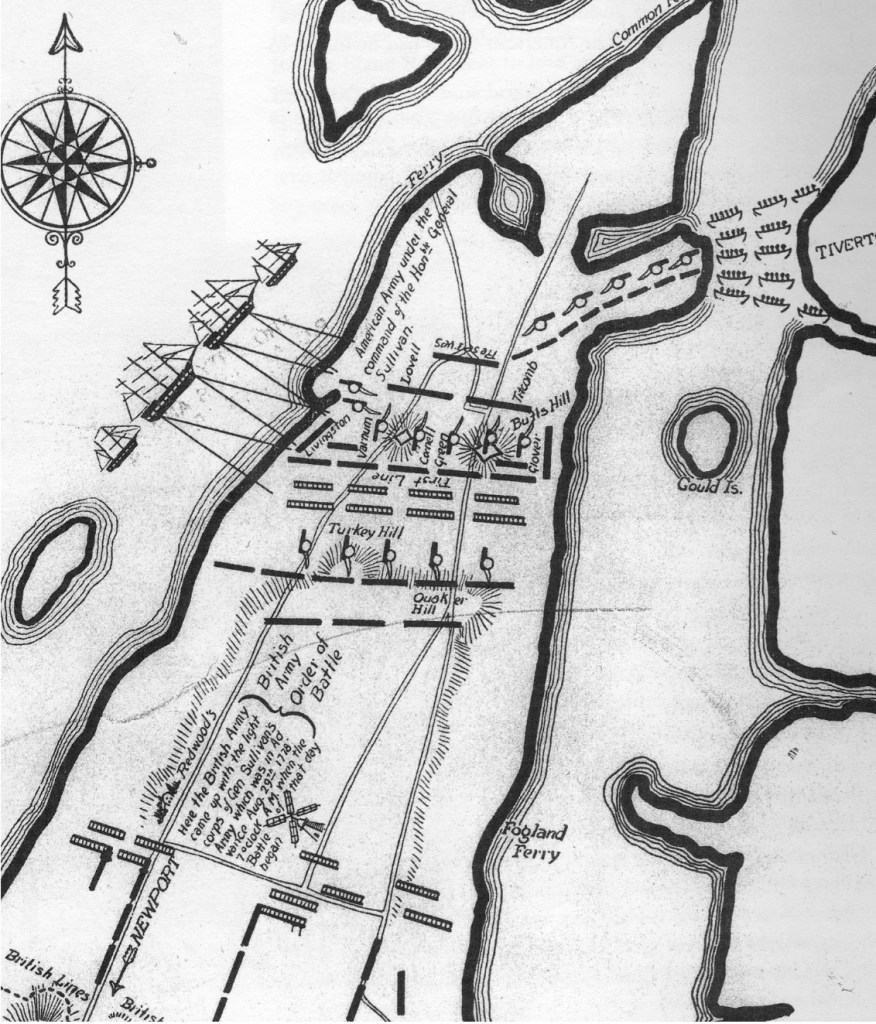

August 16th – November 28, 1780: American troops help French at Butts Hill

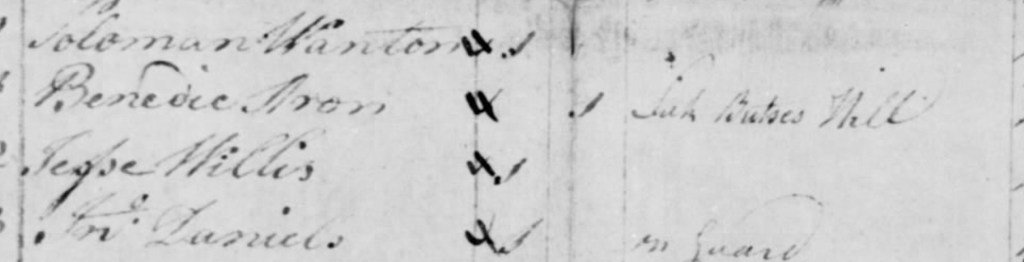

There were American troops assigned to Butts Hill to support the work of the French troops in enlarging the fortifications there. They were stationed at “Camp Butts Hill” from August 16th to November 28, 1780. Major General William Heath’s diary for September of 1780 notes that “The batteries were strengthened, a very strong one erected on Rose-Island, and redoubts on Coaster’s-Island: the strong works on Butt’s-Hill (were) pushed.” A few days later he would remark: “The French army continued very busy in fortifying Rhode-Island: some of their works were exceedingly strong and mounted with heavy metal.” We know from orderly books (daily records) that the American militiamen were aiding the French masons as they enlarged and fortified Butts Hill Fort.

January 1, 1781: The First and Second Rhode Island Regiments were consolidated into the “Rhode Island Regiment”.

March 6, 1781: Washington Visits Rochambeau

General Washington visited Count de Rochambeau to consult with him concerning the operation of the troops under his command. Washington was hoping to encourage Rochambeau to send out his fleet to attack New York City. In an address to the people of Newport, Washington expressed gratitude for the help of the French.

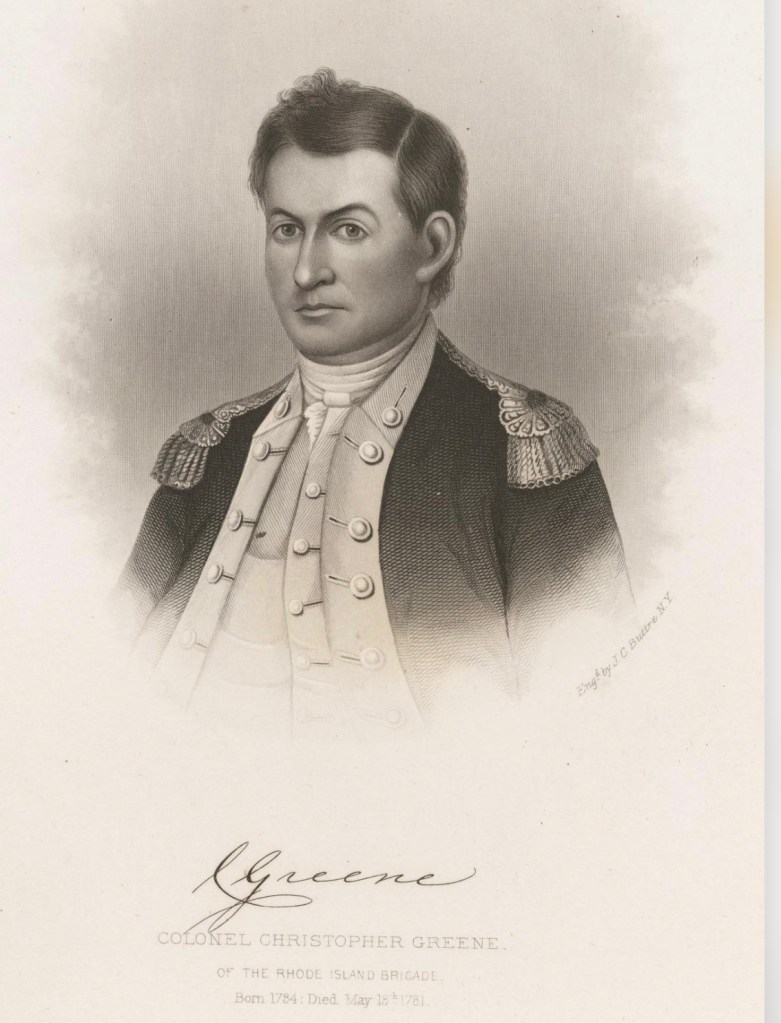

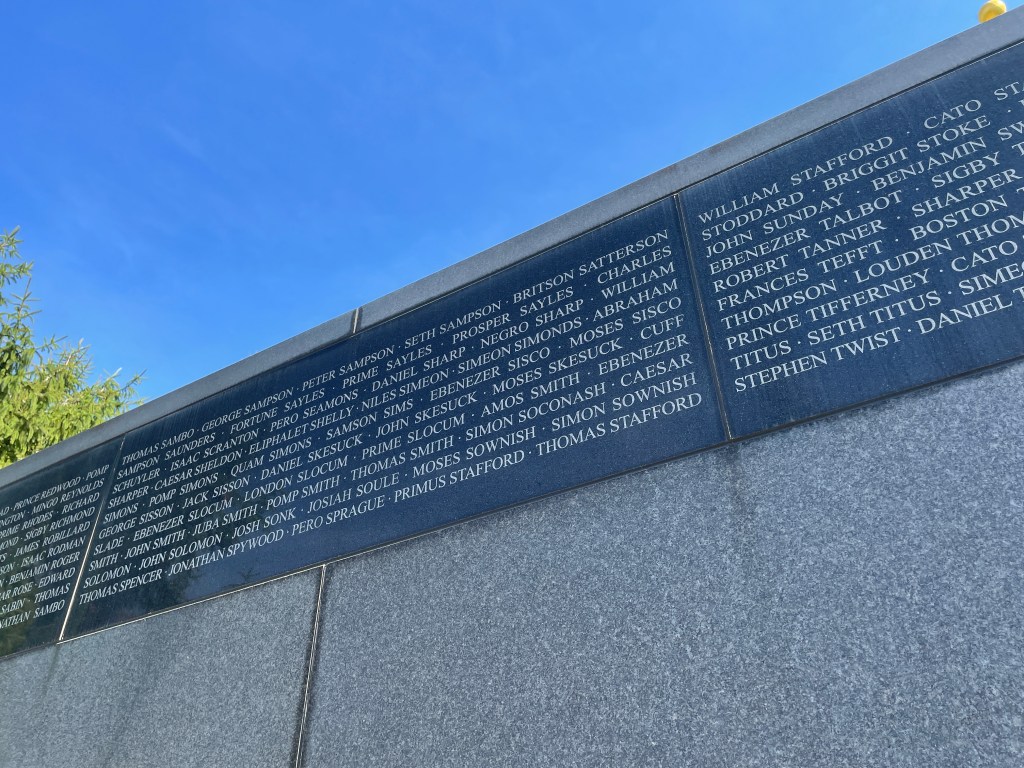

May 14, 1781: Col. Christopher Greene killed in a battle near Fishkill,

Col. Christopher Greene had charge of the Black Regiment. After the Battle of Rhode Island, Greene’s troops stayed around Rhode Island. They camped around Butts Hill and participated in the construction of Butts Hill Fort. Heading towards the action in the South, Greene and his soldiers camped near Peekskill, New York. They were guarding the Continental lines. On the morning of May, 14th a New York Loyalist unit attacked Greene’s men. They put up a fight, but Greene was killed in hand-to-hand fighting.

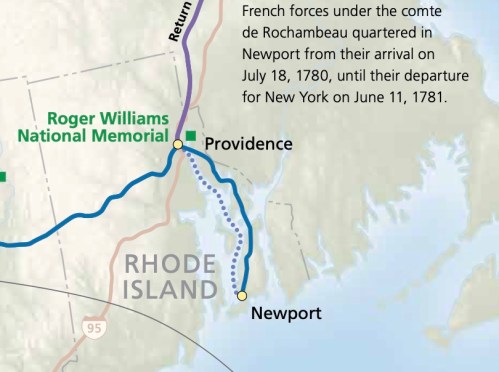

June 10, 1781: French Army starts its trail to Yorktown.

As the road to Yorktown began, Rochambeau and his general staff left Newport on June 10, 1781. He arrived at Providence the following day. Brigadier General de Choisy was left behind in Newport with some French troops. In August he sailed with Barras’ fleet to the Chesapeake area. On the morning of June 11, 1781, the first Brigade of French troops began to load onto the small vessels in the harbor of Newport. All the troops had left by the 12th and camped on the west side of Providence between Westminster and Friendship streets. The French Army performed a grand review in Providence on June 16, then set out for Coventry in four divisions. One division departed each day from June 18 to 21. Rochambeau left Providence with the first division (the Bourbonnais Regiment) and arrived at Waterman Tavern in Coventry in the evening of June 18.

14 October 14, 1781: Stephen Olney of Providence leads the final charge in the Battle of Yorktown.

Olney led the Rhode Island soldiers (including those who had been in the Black Regiment. They served under Lafayette at Yorktown. Olney led them over the top of Redoubt 10 where they were attacked by British soldiers with bayonets. The redoubt was quickly taken, but Olney was badly injured.

September 3, 1783: Final peace treaty signed in Paris