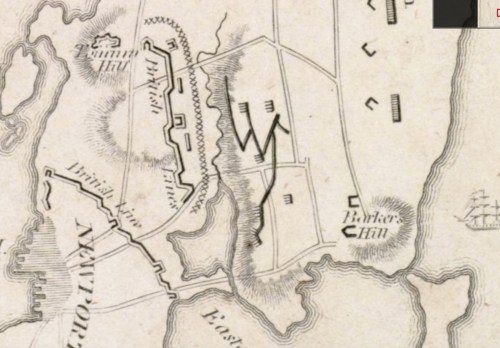

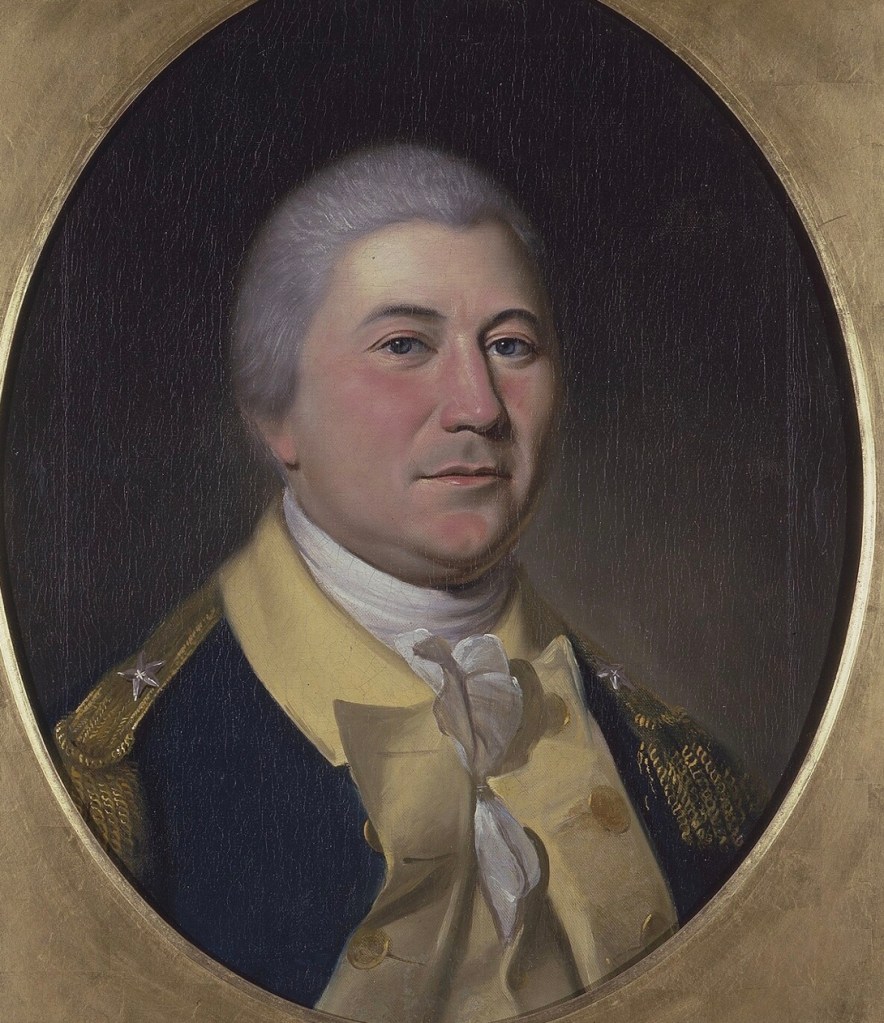

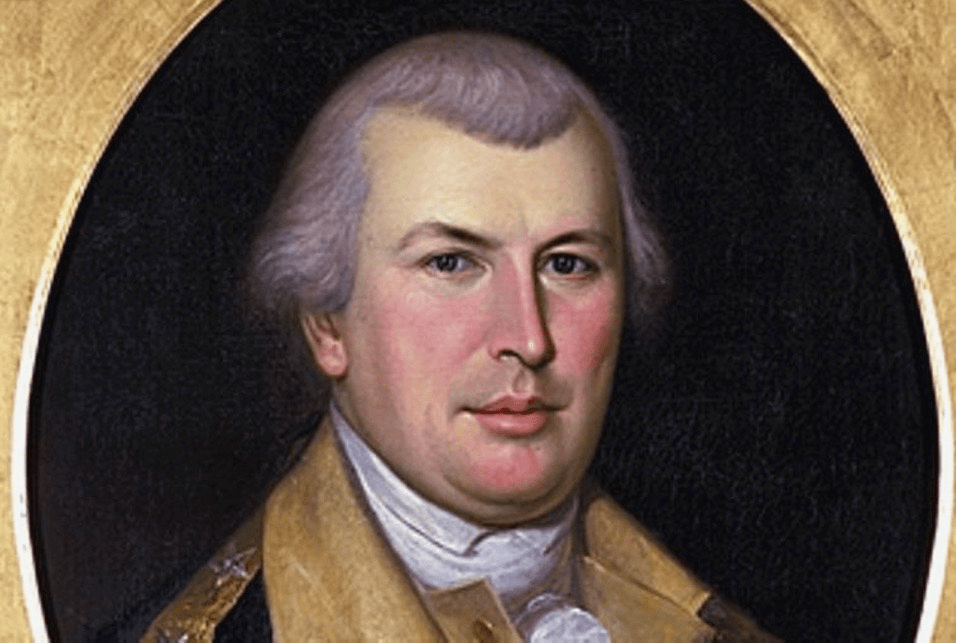

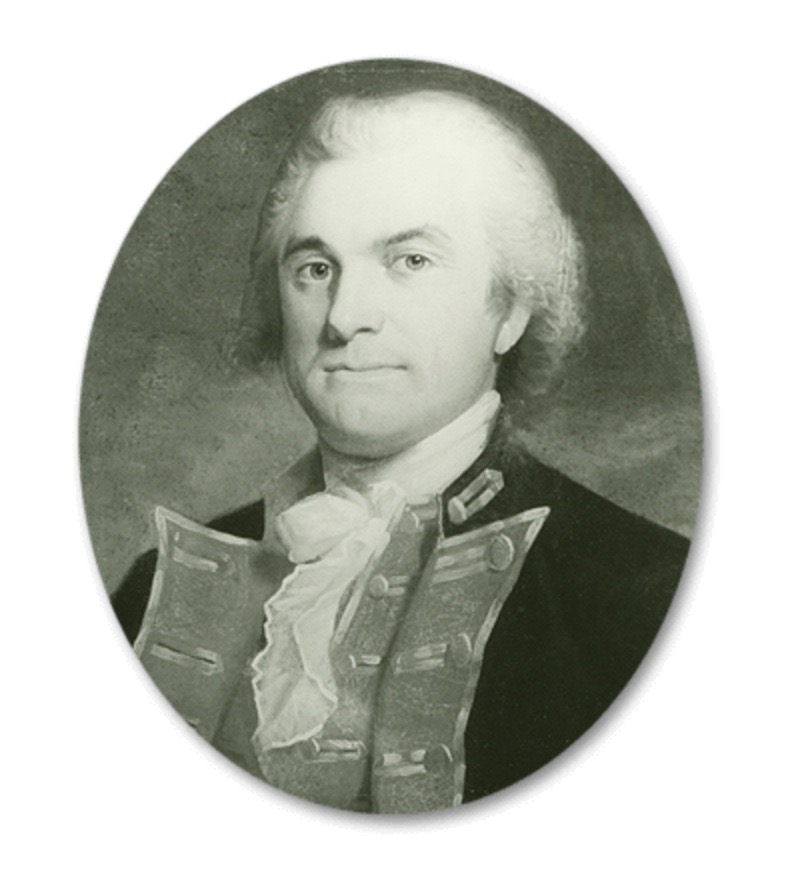

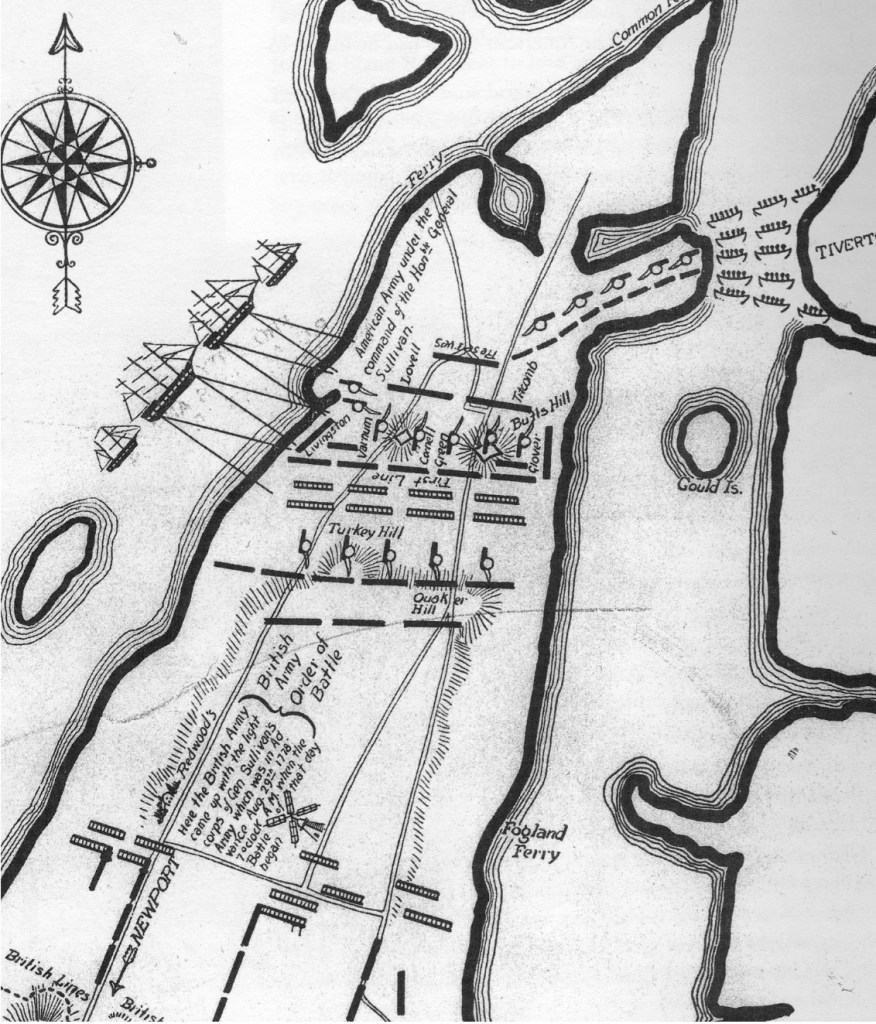

Overnight August 28 – 29, Sullivan began his preparations to defend the route to the Howland ferry towards safety in Tiverton. He positioned forces in a line from Turkey Hill by West Road and Quaker Hill on East Road. Holding this area so all his troops and baggage could get off the island was his aim. His best men, divided between militia and Continentals, were positioned to delay the British troops. John Glover commanded the troops on the left wing on the eastern side of the island. Command of the right wing was given to Nathanael Greene. Men were positioned in various positions up East and West Roads. Action in the Battle of Rhode Island took place along those two main road and Middle Road. Sometimes there were two or more actions going on at approximately the same time. This brief timeline is an approximation.

For clarification the British and Hessian leaders are noted with a (B) and the American leaders are noted with an (A).

August 29, 1778

Dawn:

*Captain Mackenzie (B) saw empty American works. He traveled to Pigot’s (B) headquarters to inform him of withdrawal. Pigot decided to hamper the retreat.

6:30 AM:

*General Prescott (B) moved out with the 38th and 54th Regiments to occupy fortifications at Honeyman’s Hill in Middletown.

*Brigadier General Smith (B) marched toward Quaker Hill by East Road with 22nd and 33rd Regiments with the flank companies of the 38th and 54th.

*On West Road Captain von Malsburg (B) and Captain Noltenius (B) with Hessian Chasseurs advanced toward Laurens (A). Behind them came Major General von Lossberg (B) leading two Anspach battalions.

7 AM:

*Von Malsburg (B) spotted Laurens (A) and Talbot (A) with their Light Corps behind stone walls to the south of Redwood House. Americans were driven back up West Road.

*Livingston’s men (A) attacked Smith’s men (B) from behind stone walls on East Road.

Commander Pigot ordered von Huyne’s Regiment (B) and Fanning’s Regiment (B) to support von Lossberg (B) on West Road.

*Pigot (B) orders Prescott (B) to send 54th Regiment and Brown’s Regiment to reinforce Smith (B) on East Road.

8 AM:

*Von Lossberg (B) sent troops toward Lauren’s positions on three sides.

*Coore’s and Campbell’s troops (B) ran into a group of Wade’s (A) pickets by the intersection of East Road and Union Street.

*British moved down Middle Road and East Road toward Quaker Hill.

8:30 AM:

*Von Lossberg (B) came to the aid of Hessian Chasseurs.

*Laurens (A) and his Light Corps was forced to retreat across Lawton’s Valley to the works on a small height in front of Turkey Hill.

*Lauren retreated to Turkey Hill. Laurens was told to retire to the main army as soon as possible.

Hessian (B) attackers arrived on top of Turkey Hill.

9 AM:

*Wigglesworth’s Regiment (A), Livingston’s Advanced Guard (A) and Wade’s pickets (A) waited for British at the intersection of East Road, Middle Road and Hedley Street.

*Quaker Hill was the scene of intense fighting.

*Americans retreated toward Butts Hill and Glover’s (A) lines.

9:30 AM:

*From top of Quaker Hill, Smith (B) could see strength of Glover’s position.

*Smith was under orders not to begin a general engagement, so he decided against a frontal assault. *Smith withdrew forces to the top of Quaker Hill.

*10 AM:

*Von Lossberg’s (B) troops arrived at Turkey Hill.

*Americans had positions on Durfee’s Hill and Butts Hill.

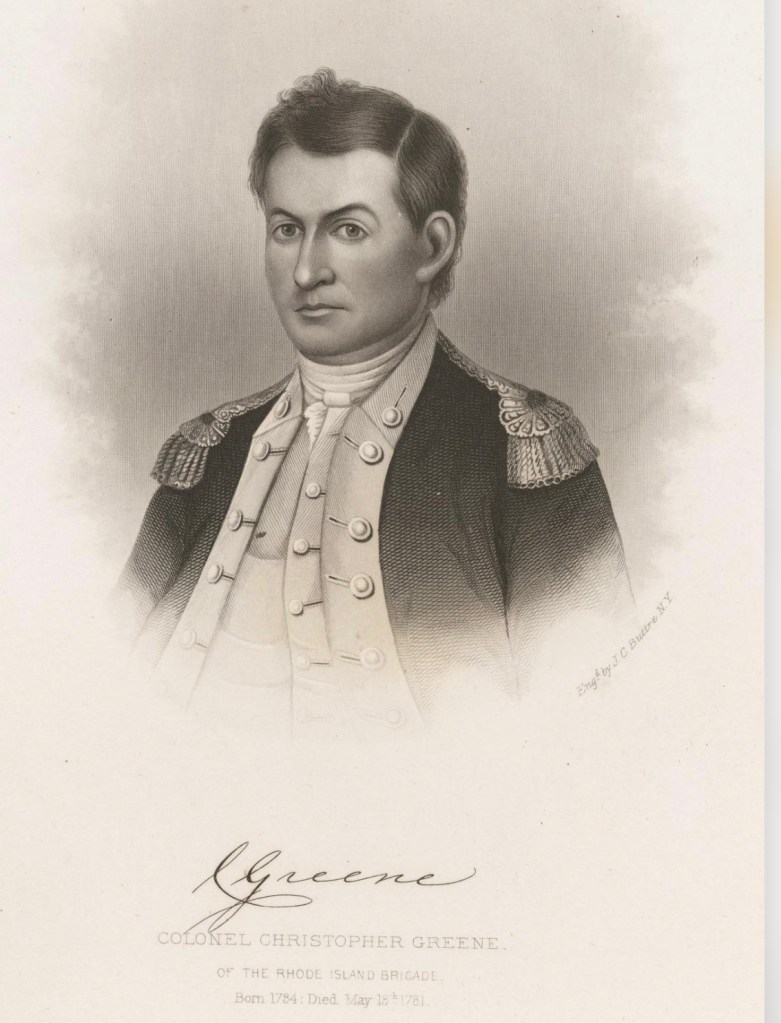

*Samuel Ward (A) and the 1st Rhode Island Regiment (Black Regiment (A)) held an Artillery Redoubt. *His men repulsed von der Malsberg’s (B) men.

11:30 AM:

*Von Lossberg (B) ordered von der Malsburg’s men (B) to try to attack Ward’s (A) First Rhode Island Regiment position again.

*British ships Sphynx, Spitfire, and Vigilant shelled the American positions from the West shore, but they did little damage.

*The Americans held their position.

1PM:

*British ships planned to attack American positions.

*General Greene’s (A) men dragged cannon down to the beach and forced the British ships to retreat.

2 PM:

*Pigot (B) reached Quaker Hill to observe the action.

*Pigot ordered Landgrave (B) and Ditfurth Regiment (B) to march to von Lossberg’s (B) troops.

4PM:

*General Glover (A) saw movement in British lines and ordered Tyler’s Connecticut militia (A) and Titcomb’s (A) Brigade of Massachusetts militia to positions behind stone walls (maybe Freeborn Street), but the British did not engage.

7PM:

*Landgrave (B) and Ditfurth (B) Regiments arrived at von Lossberg’s lines.

7PM (August 29) to 3AM (August 30) :

*There was sporadic artillery fire and light skirmishing. Musket and cannon shots were heard for seven hours.

*The Battle of Rhode Island was basically over.

*The Americans and British forces retired to their lines.

Aftermath of Battle

August 30

Sullivan assigns men to bury the dead. The wounded are ferried to hospitals on the mainland. American troops use the day to rest and recover. Sullivan receives word that d’Estaing is not coming back. He also receives a letter from Washington warning that Howe’s British fleet is on the way. The fleet is observed off Block Island. Sullivan moved quickly to complete a retreat off Aquidneck Island, but he staged Butts Hill to look like they were fortifying for a fight.

6PM:

*After all the baggage had been removed, Sullivan issued the order for all his men to depart the island.

11 PM:

*Lafayette returns from Boston. He assumes supervision of the retreat of the last of the pickets. He orders the building of fires to suggest the army was hunkering down.

*By midnight: Most of the troops are off the island.

August 31st: By 3 AM all the troops are on Tiverton side.