A friend let me know that the old sheep shed at Glen Farm is gone. Only the foundation remains. When my Elmhurst students interviewed the Camara sisters many years ago, Geri Leis talked about this shed fondly. This is her clubhouse in the 1940s. In honor of the memories of the Sheep Shed, I am posting clips from interviews the Camara Sisters where they talk about what it was like to play on Glen Farm.

Playing on Glen Farm: The Camara Sisters Interviews

January 3, 2024

Portsmouth History Glen Farm Leave a comment

Preserving the Glen Farm Ice House

January 2, 2022

Portsmouth History Glen Farm, Ice House Leave a comment

Are you old enough to remember when an “icebox” was used instead of a refrigerator? Ice houses were an important tool in keeping that ice cold to meet refrigeration needs over the summer.

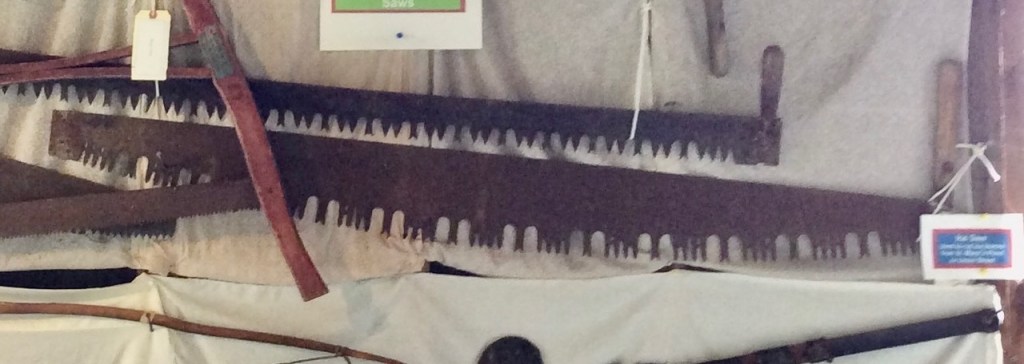

A hundred years ago this week, January 1922, the Newport Mercury reported that ice was being harvested from St. Mary’s “Lake.”

“The severe cold on Monday did not stop the preparations made for harvesting ice at St. Mary’s Lake. Ice about nine inches thick was cut and the ice houses at Oakland Farm have Benn filled. Those at Glen Farm are being filled and the men at Sandy Point Farm were to start on Thursday morning.” (Npt. Mercury 1/7/1922)

In the collection of the Portsmouth Historical Society is an ice saw with one handle that was actually used to cut ice at St. Mary’s Pond.

Part of that ice was going into a little ice house at Glen Farm. As part of the Glen Farm complex, an ice house was extremely important to farmers like H.A.C. Taylor who owned a dairy. The Newport Mercury in June of 1896 reports that H.A.C. Taylor was having an ice house built by Edward Coggeshall. It measured 24 feet by 16 feet and had a gambrel roof. The house would have very thick insulation to keep the ice cold through the warmer seasons.

Portsmouth is blessed with many historical buildings and it is always good news when efforts are made to preserve these properties. On December 13, 2021, the Portsmouth Town Council voted to use some modest funds to repair and stabilize the Glen Farm Ice House. These funds go a long way to making the ice house a useful town owned building. Portsmouth’s history in many ways revolves around its agricultural heritage and “gentlemen farms” like Glen Farm are part of that history we should celebrate.

Stories from the Graveyard: Tragedy for the Slocums

October 29, 2021

Portsmouth History Glen Farm, Graveyards, Slocum Leave a comment

Graveyards don’t scare me. As an historian I sometimes feel like I know some of the people whose graves I pass. A few years ago my husband and I volunteered to survey the little graveyard by the barns at Glen Farm as part of a state-wide effort to monitor the historic cemeteries. The sturdy stonewalls protect it from the bustle of equestrians who come to ride or take care of their horses. Once you step inside that tree shaded historical cemetery you may notice that the gravestones tell the story of two families, the Cundalls and the Slocums. The Cundall burials range from 1810 to 1820 and they are on the westside of the plot and the head of the stones face west.

The headstones for the Slocum family are of an earlier time – 1703 to 1722. They lie in the northeast corner of the plot and the engravings face south. According to the database of historic cemeteries, the grave of at least one young Slocum lies here unmarked by a stone. Two of Giles Slocum’s sons died together in 1712. Their names were Matthew and Giles. How did two of the Slocum children die together? It was murder so evil that even Boston newspapers (Boston News Letter-June 27th, 1712) carried the account.

“An Indian servant man belonging to Mr. Giles Slocum of Portsmouth carried out to sea in a canoe two of his Master’s sons, one of them ten, the other nine years old. …Being examined before authority he confessed that he knocked the eldest child in the head with a paddle. Seeing the youngest crying, he overset the canoe by design and swam to shore by himself.”

Later reports tell us that the servant’s name was Job. A fitting name for one who would find himself “now in irons in prison till he is tried for murder.” I would assume it would be the same jail our friend Thomas Cornell was locked in forty years before. Why did Job commit the crime? Was he angry at the boy? Was he drunk? – a common problem in those days. We can only wonder. We will never know his motive, but we do know his end. He was hung in chains (gibbeted) at Miantomi Hill. That’s the same place Thomas Cornell met his end. Whereas Thomas was duly buried, Job was not. Criminals suffered the gibbet if their crimes were particularly heinous. The body is left suspended and decaying for all to see. He was left to rot on the gallows for two years or as an early historian would note, “until his bones fell apart from decay of the flesh and ligaments.”

Portsmouth Farmer: Manuel Camara (1900-1991) of Glen Farm

August 21, 2020

Portsmouth History Glen Farm, Portsmouth Farms Leave a comment

Manuel Camara was a dedicated worker at Glen Farm for over sixty-four years. In a Newport Daily News interview in 1984, Camara said “The Taylors are excellent people to work for, that’s why I’ve stayed here all these years.” While at Glen Farm, Camara worked for two generations of the Taylor family. After Edith Taylor Nicholson’s death in 1959, the farm land began to be sold. Manuel Camara began to work in the glory days of the Gentleman’s Farm and continued on until almost the last days when he was one of three workers.

“It’s funny that I even took the job here. I hated driving my father’s plow horses and that’s what they had me doing here (at Glen Farm). Boy was I happy when they got the tractors in.”

Camara grew up in Tiverton and left his father’s farm to become a farm hand at age 21. When Camara started at Glen Farm there were sheep, cattle, dairy cows, poultry and horses. The “gentleman’s farm” was over 1,000 acres. Manuel worked his way from farm hand to herdsman, and then foreman of the farm.

Like many of the Glen Farm workers, Manuel’s family lived on the farm. At one time they lived at the Leonard Brown House. His daughters, Geraldine Leis and MaryLou Lemieux, have shared their experience of growing up on the farm. Manuel would warn his family to get into the house because they were going to “stampede the cattle.” This was when they had to move them from one field to another. When Manuel became a foreman he spent more time at the barns. Daughter Geraldine, the youngest of his four daughters, would get into trouble by playing in the hayloft and trying to ride the cows.

As Glen Farm diminished in size, Manuel kept active. His day would start at 7 am. As the daily farm chores began he would feed and water the cattle, clean the stalls and clean-up the barnyard. “We bail a lot of hay here.” he mentioned to the reporter. Manuel would also plant and harvest corn. He complained that winter could be slow, “but spring is always around the corner and that means more hard work.” Manuel Camara was never afraid of hard work. Although he ultimately retired, he told the reporter “So I guess I’ll stick around until I can’t work any more.”

H.A.C. Taylor and The Glen Barns

August 15, 2020

Portsmouth History Glen Farm, Missy of the Glen, Portsmouth Farms Leave a comment

Glen Farm developed when Henry A.C. Taylor, a successful banker and merchant from New York, began to purchase farmland in Portsmouth. Taylor had vacationed in Newport and owned a house there, but he liked the idea of a working farm. The first purchase was 111 acres from Halsey Coon which included two houses, a grist mill, two barns, and two corn cribs. An 1885 map shows that this piece of land stretched from the Sakonnet to the barn complex. In 1885 Taylor bought 700 acres around Glen Road and he officially established Glen Farm. Taylor began to buy and consolidate the smaller farms in the area into a farm that would at one time reach 1500 acres.

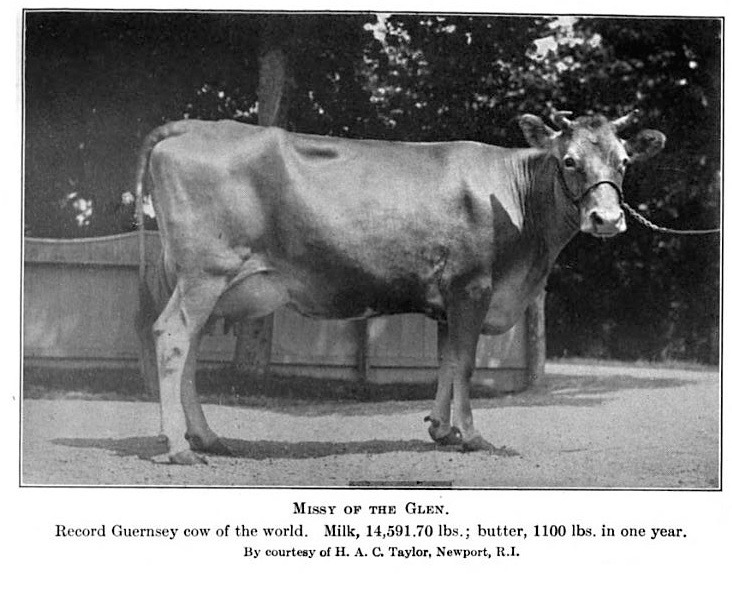

In 1889 he began to breed Guernsey cows and would later breed Percheron horses and Horned Dorset sheep. He was very serious about scientific breeding and kept detailed records of milk and fat production as well as the number of calves born.

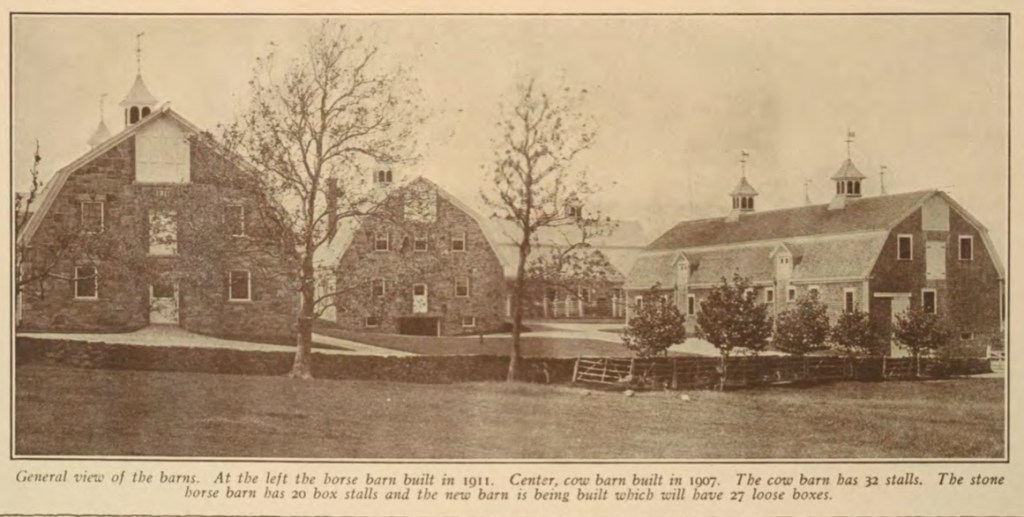

An October 1911 to March 1912 quarterly edition of National Magazine has an article on Rhode Island farming that details Taylor’s efforts with Glen Farm. Taylor’s intention was “not merely to develop an ideal farm, but also to establish a herd of Guernsey cattle upon the place that should attain and hold pre-eminance in this country.” Taylor spared nothing in raising the best. He hand picked the cattle from the Isle of Guernsey.

The article goes on to explain that the arrangement of the barns and stables and their construction were all specifically designed. The last of the barns built was especially modern. “There was an inner wall of brick with a six inch air space between it and the outer wall, which supplies proper ventilation and insures a uniform temperature within.” Even the drinking basins for the animals have water “tempered by the furnaces in the basement which warm the buildings.”

Mr. Barclay, the farm manager, explained that H.A.C. Taylor instructed him “not to study how to make money, but how to spend money in ways that will conduce to the highest development of his pets and pride, the Guernseys of Glen Farm.” Even with that instruction, Glen Farm was exceedingly profitable. The stock raised at Glen Farm was very desirable.

H.A.C. Taylor was proud of his animals. The walls of the manager’s office were lined with hundreds of prize ribbons. When a friend challenged his claim that “Missy of the Glen” had set a record for butterfat production, he brought a lawsuit that went all the way to the U.S. Supreme Court. Taylor won the suit but paid more for the lawyers than he won in the judgement.

At least twenty-six families lived and worked on the farm. In its heyday there were up to 100 workers. They raised all they needed for the families and the animals.

If you are interested in more information on the Glen and Glen Farm, you might visit my other blog: glenhistory.wordpress.com