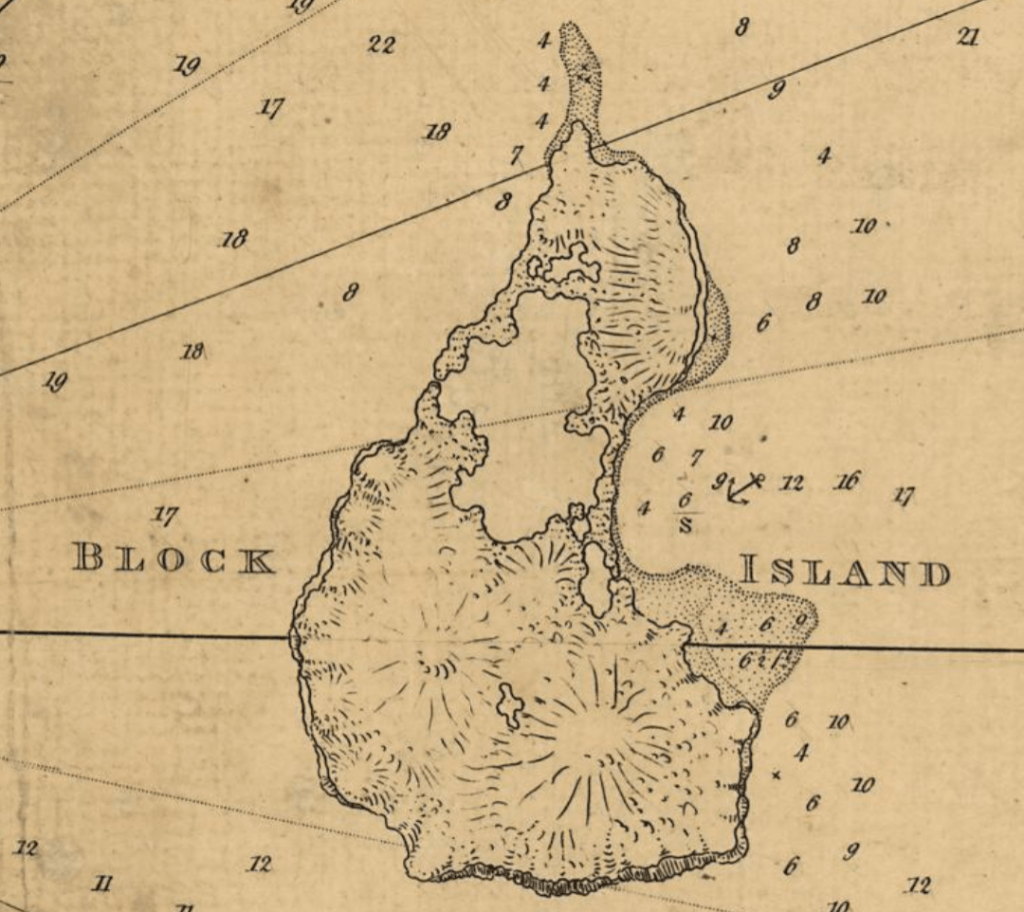

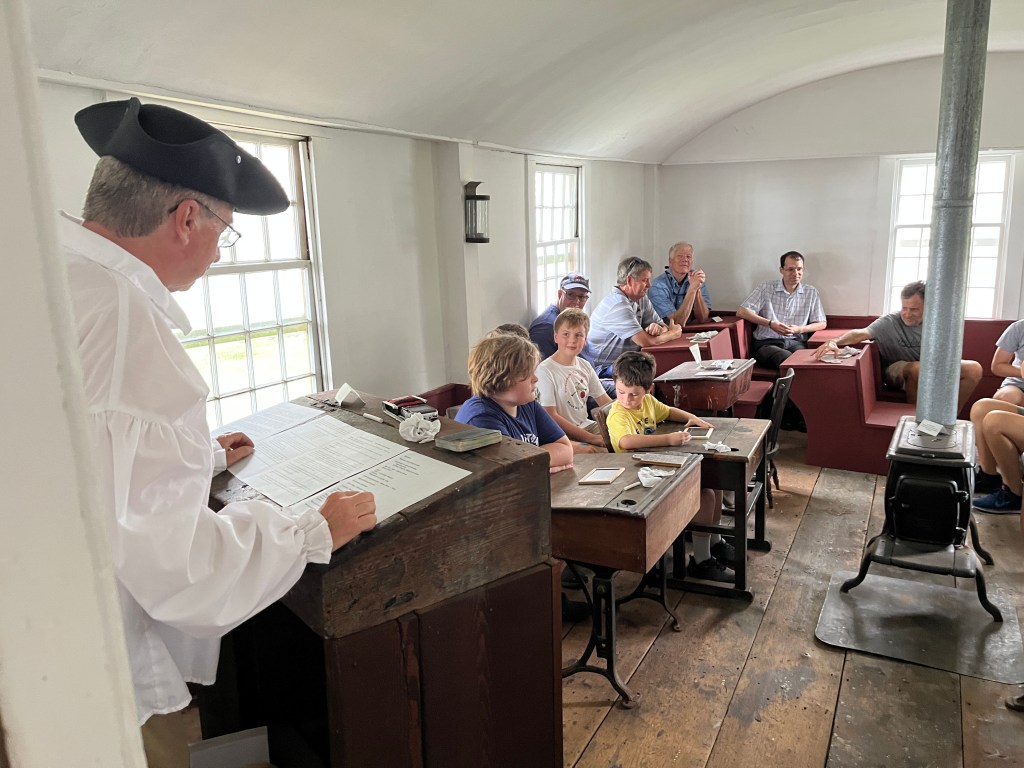

Although Block Island remained neutral in the Revolutionary War, they expressed their unity with other Rhode Island communities in a Town Meeting at New Shoreham, March 2, 1774. According to Livermore’s “History of Block Island,” Newport had sent a copy of resolves on the tea duties and Block Island was asked to unite with the other towns in the Colony. The resolves voted by the Town Meeting give us a glimpse of the grievances of the Americans.

What were the tea duties?

Americans were consuming smuggled tea and that hurt the profits of the East India Company. This company was a private business, but it was important to Britain’s economy. The British Parliament passed the Tea Act in 1773 to give the East India Company the right to ship its tea leaves directly to America. Only the East India Company could sell tea in the colonies. This lowered the price of East India Company’s tea in America. This forced the colonists to pay a tax of 3 pennies on every pound of tea. The Tea Act thus retained the three pence Townshend duty on tea imported to the colonies. The money was to go to the support of the British Army in the colonies.

What were the Block Island Resolves?

I am listing the resolves, bolding what struck me, and commenting briefly on the concern of the Block Islanders with parentheses.

- Therefore we the inhabitants of this town, being legally convened in town meeting, do firmly resolve, as the opinion of said town,

- 1. That the Americans have as good a right to be as free a people as any upon the earth; and to enjoy at all times an uninterrupted possession of their rights and properties, (Americans were concerned about maintaining their rights and properties)

- That the act of the British Parliament, claiming the right to make laws binding upon the Colonies, in all cases whatsoever, is inconsistent with the natural, constitutional, and charter rights and privileges of the inhabitants of this Colony. (Acts like the Tea duties go against the colonial rights given in colonial charters).

- That the express purpose for which the tax is levied on the Americans, namely, for the support of government, administration of justice, and defense of His Majesty’s dominions in America, has a direct tendency to render Assemblies useless, and to introduce arbitrary government and slavery. (The duty is suppose to go toward the support of British forces in America. This overrides the authority of the Colonial Assemblies.)

- That a tax on the inhabitants of America, without their consent, is a measure absolutely destructive of their freedom, tending to enslave and impoverish all who tamely submit to it. (The phrase “no taxation without representation” is evident here. The Americans have not voted for this.)

- That the act allowing the East India Company to export tea to America, subject to a duty payable here, and the actual sending tea into the Colonies, by said Company, is an open attempt to enforce the ministerial plan, and a violent attack upon the liberties of America. (As East India Company is the only sanctioned tea importer, this violates the right to choices in America.)

The other parts of the Block Island resolutions give us an idea of the sympathies of the islanders.

- That it is the duty of every American to oppose this attempt. (This is a strong statement of duty to oppose.)

- That whosoever shall, directly, or indirectly, countenance this attempt, or in anywise aid or assist in running, receiving, or unloading any such tea, or in piloting any vessel, having any such tea on board, while it remains subject to the payment of a duty here, is an enemy to his country. (Even stronger language calling those who assist in this are enemies.)

- That we will heartily unite with our American brethren, in supporting the inhabitants of this Continent in all their just rights and privileges. (This is a call to unity with the colonists).

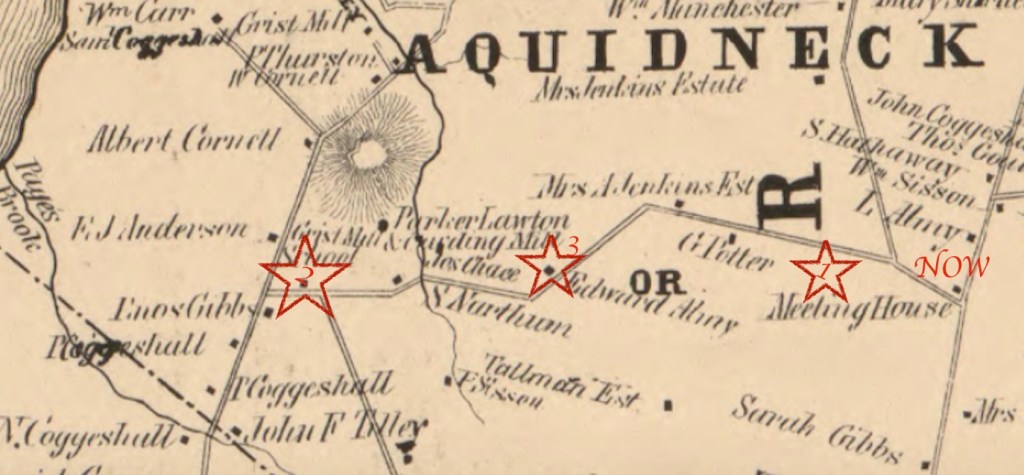

- That Joshua Sands, Caleb Littlefield, and John Sands, Esqs., and Messrs. Walter Rathbone, and Edward Sands, Jr., or the major part of them, be appointed a committee for this town, to correspond with all other committees appointed by any town in this Colony; and said committee is requested to give the closest attention to everything which concerns the liberties of America; and if any tea, subject to a duty here, should be landed in this town, the committee is directed and empowered to call a town meeting, forthwith, that such measures maybe taken as the public safety may require.

- And we return our hearty thanks to the town of Newport for their patriotic resolutions to maintain the liberties of their country ; and the prudent measures they have taken to induce the other towns in this Colony to come into the same generous resolutions.

WALTER RATHBONE,

Town Clerk:’

Perhaps the sympathies of the Block Islanders were with the other towns in Rhode Island – even if later they technically remained neutral.

Reference: Livermore, ST. A History of Block Island. Block Island Historical Society – 14th printing 2024 (original 1877).