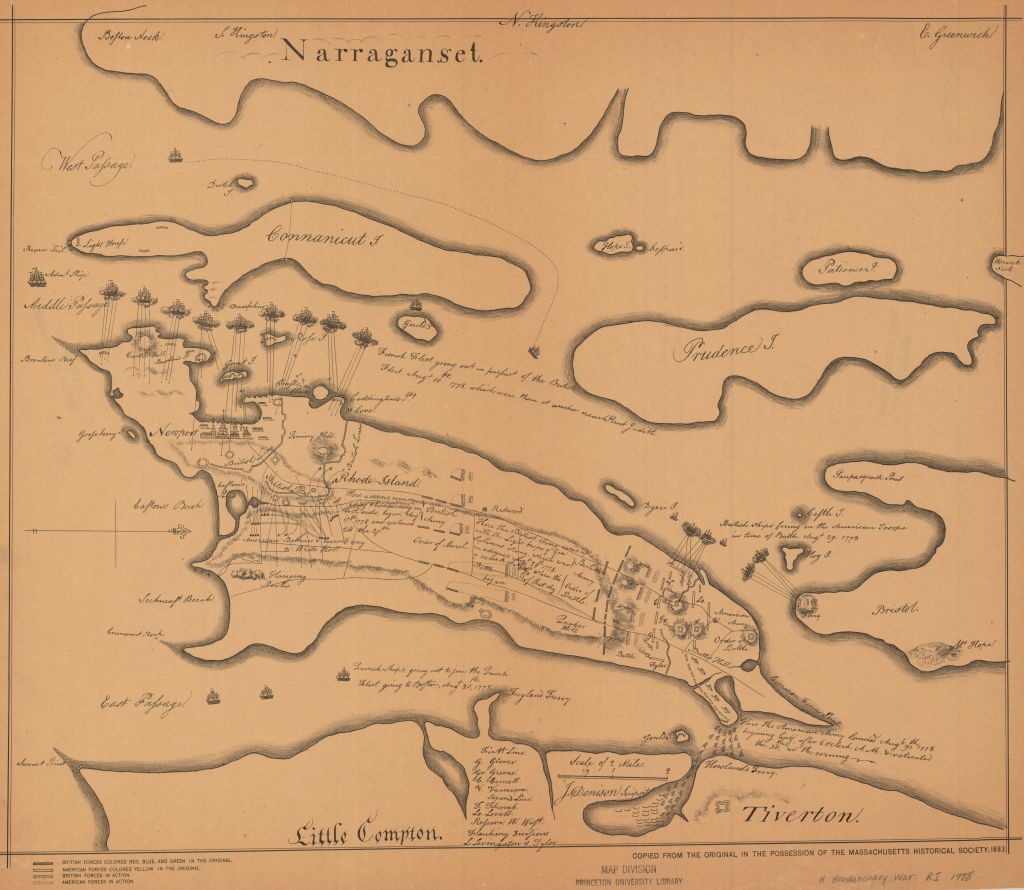

The Occupation of Aquidneck Island dragged on for almost two years when a plan was devised to work with French allies in pushing the British out of the island. On May 4, 1778 Congress ratified a treaty of alliance with France. The Rhode Island Campaign was devised as a wedge action. The Americans, under the leadership of John Sullivan, would cross from Tiverton to Portsmouth and drive south to set up a siege of Newport. Meanwhile the French, led by d’Estaing, would arrive by sea and attack the British from the sea.

July 11, 1778, Continental Congress authorized Washington to request the northeastern states to raise militia for a joint operation with the French.

July 20, 1778, d’Estaing announced he would sail for Newport and not the alternate target of New York.

July 22, 1778, Washington’s delayed letter informs Sullivan that the French fleet is headed to Newport, and he directs Sullivan to increase the size of his militia forces from 5000 to 7500. Varnum’s and Glover’s brigades along with an additional attachment under Henry Jackson would head towards Providence.

July 27, 1778, Washington dispatches two Continental Army divisions under General Nathanael Greene and General Lafayette to Rhode Island. Although Greene was the Army Quartermaster, he was anxious to have a command, especially in his home state.

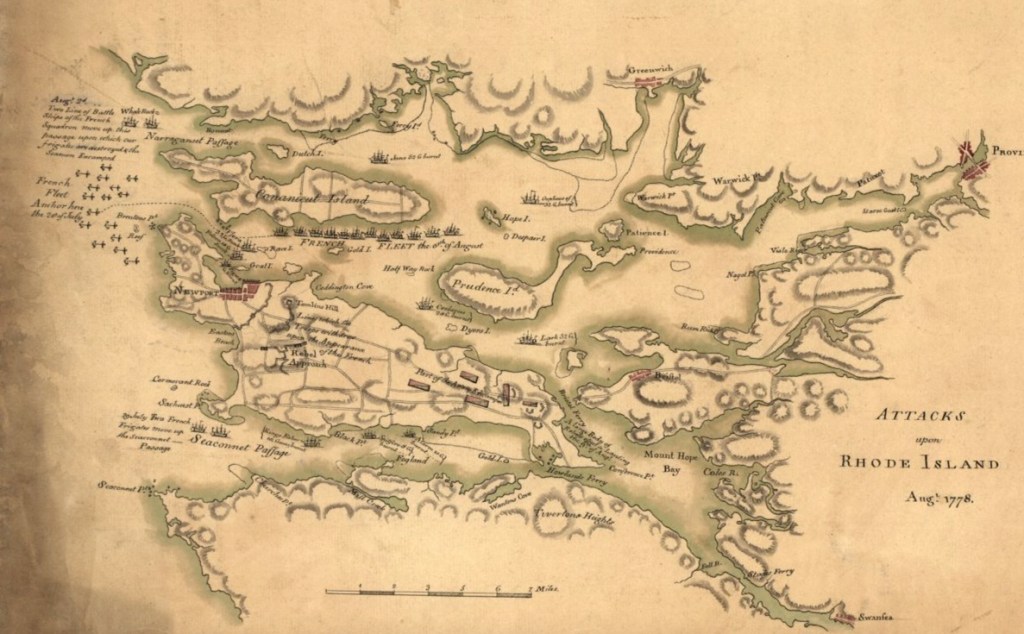

July 29, 1778, French ships arrive at Narragansett Bay. Washington had arranged for pilots to guide the French ships in the Bay. Two or three ships were stationed in the shallow Sakonnet River to the East of Aquidneck Island. Other ships positioned anchored near the entrance to the Sakonnet Channel. Most of the French ships had anchored about three miles south of Conanicut Island (Jamestown).

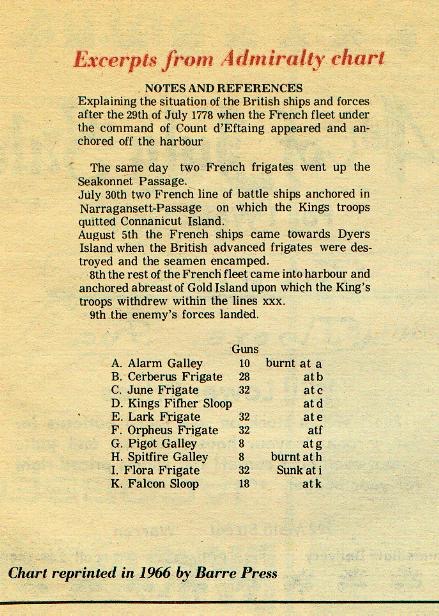

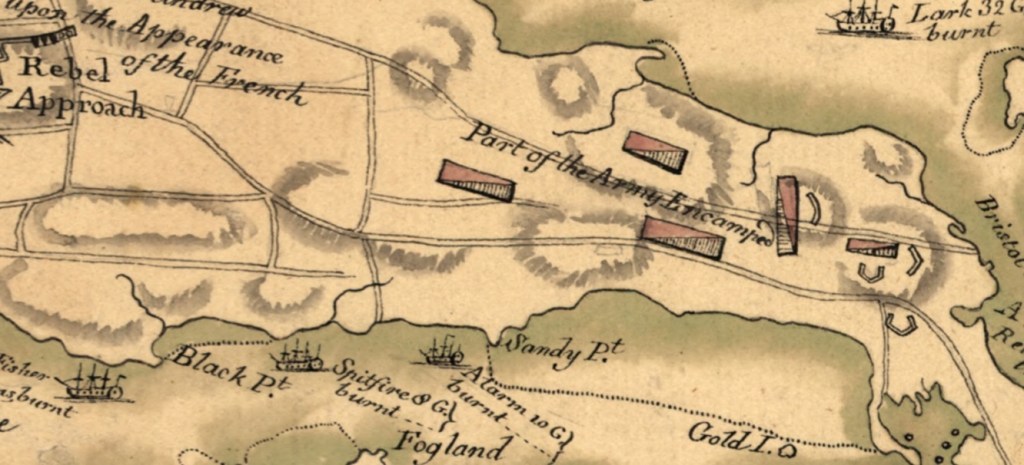

Four British frigates anchored at various points of the west side of Aquidneck Island where they would remove their cannons, ammunition and supplies. On the Sakonnet side the Spitfire and Alarm and the sloop Kingfisher were unloading at Fogland Ferry. In Newport harbor the Flora and Falcon did the same.

July 30, 1778, trapped by the French navy, British ships the Kingfisher, Alarm and Spitfire were ordered to be torched. Ammunition that had remained on the vessels caused explosions.

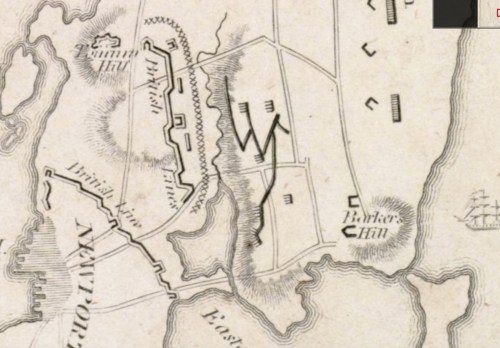

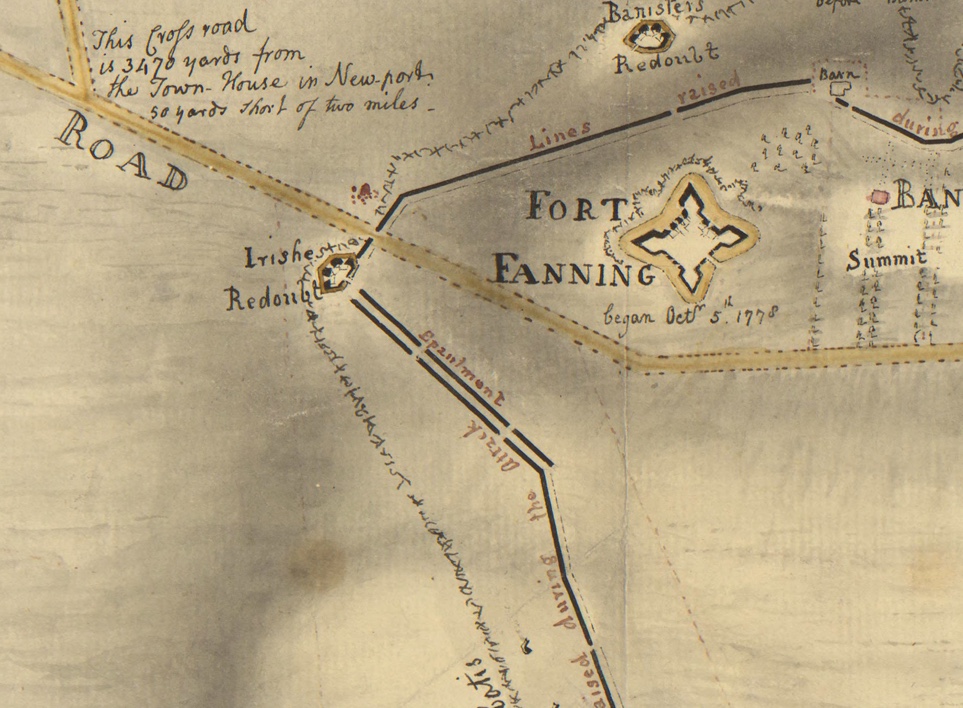

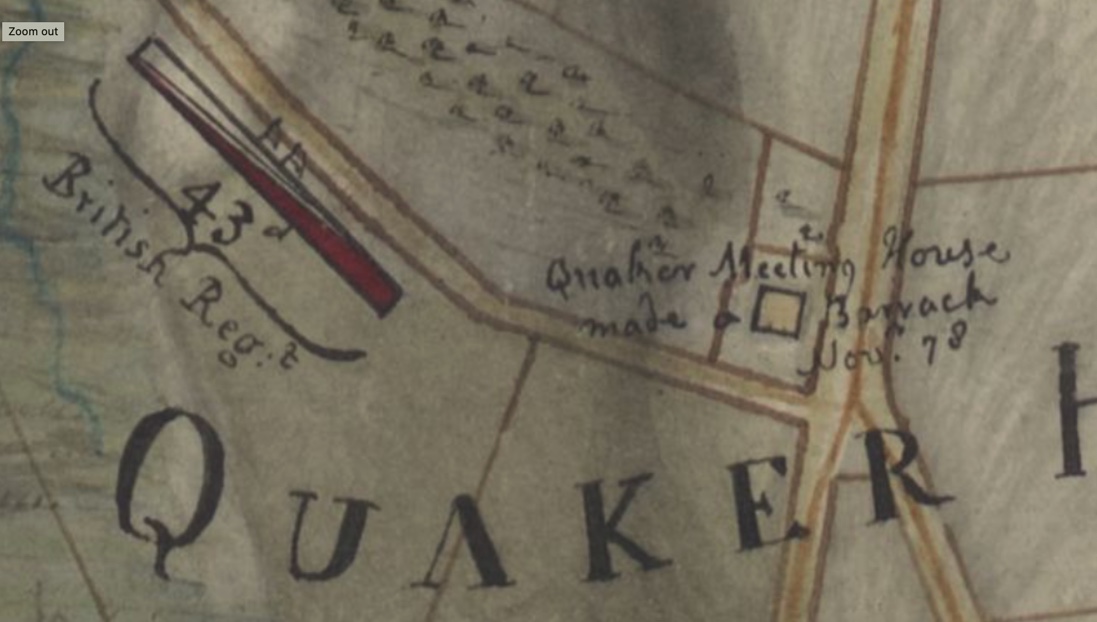

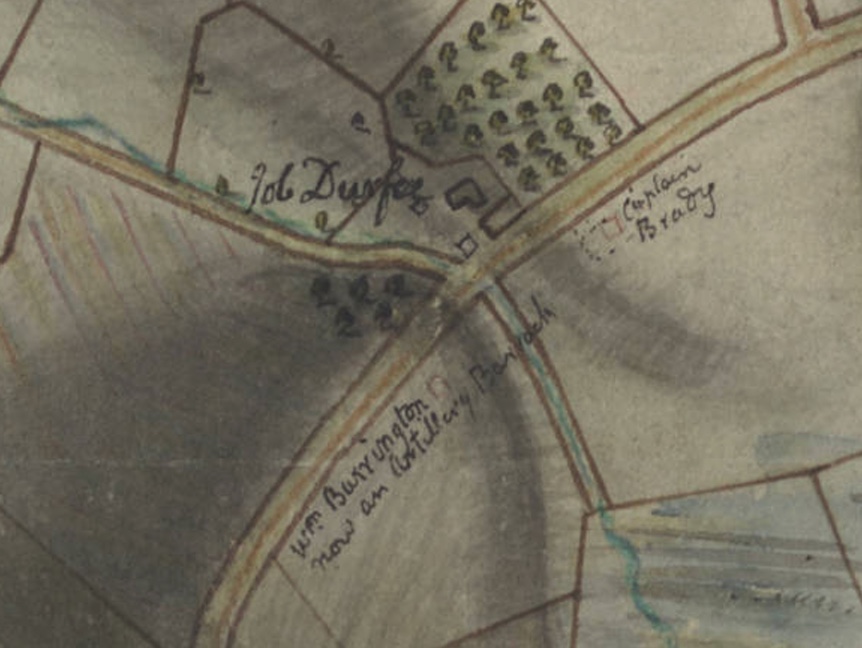

August 1, 1778, General Sullivan and Admiral d’Estaing meet, agree on simultaneous attacks on the Island on August 8. British Commander Pigot was expecting a siege and he ordered all sheep and cattle in Portsmouth and Middletown (except one per family) to be driven behind British lines in Newport. Carts, wagons, and tools like picks and axes were all collected and brought to Newport. The soldiers’ families and regimental baggage were brought to Newport. Wells in Portsmouth and Middletown were filled in so there would be no drinking water for the enemy.

August 3, 1778, British forces felled trees to block the roads running from Portsmouth and Middletown into Newport. To prevent the French from landing their troops, five or six transports were sunk by Goat Island. One of them (the Lord Sandwich) had been James Cook’s ship Endeavour.

August 5, 1778, more British ships (Orpheus, Lark, Cerberus, Juno and Pigot) were purposely sunk in the harbor to hinder the French and to avoid their capture.

August 6, 1778, Due to late arriving militia, Sullivan informs d’Estaing of postponement of the attack. British cannons fire on French ships.

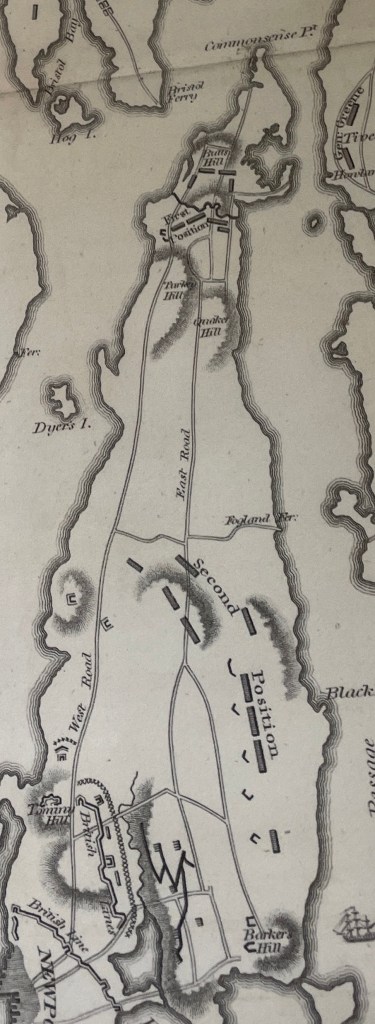

August 7-8, 1778, d’Estaing enters Narragansett Bay, causing the British to withdraw from north end of the Island into prepared positions along the Newport-Middletown border.

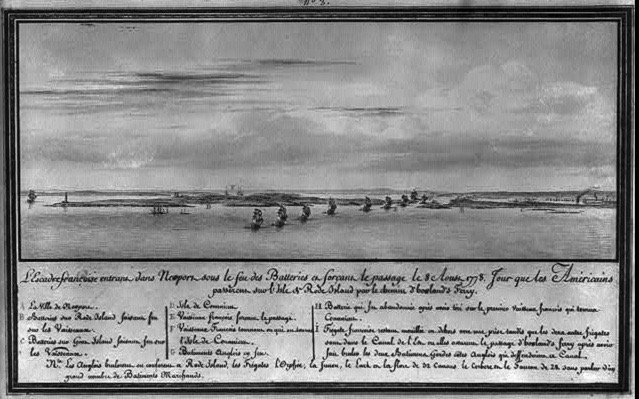

August 9, 1778, Realizing the British had withdrawn south, Sullivan moves his forces onto the Island. Two to three thousand French forces land on Conanicut Island. D’Estaing is furious that the Americans have reached Aquidneck Island early. D’Estaing is alerted to the imminent arrival of Howe’s fleet which was coming from New York. He decides to go out and fight Howe’s fleet and then go to the aid of the Americans. There was shelling between the French fleet facing Newport and the shore batteries controlled by the British.

August 10, 1778, French head out to sea. Both French and British fleets maneuver for advantage, but before they can engage, both fleets are scattered and damaged by a hurricane. Both leave for port and repairs. American commander John Sullivan prepared to shorten the distance between the American lines and the British line. He was going to lay a siege because by then he had 11,000 men.

August 11 – 12, 1778, General Sullivan prepares to work toward British positions, but the hurricane causes him to delay. The weather during the night of the 12th was especially fierce and the Americans had little shelter from the pelting rain and wind. The camp was a swamp.

For the British and French fleets out on the water, the weather turned to serious wind gusts. Heavy rain, gale force winds and thick fog hampered both fleets. The winds began to topple the masts. By 4 am on the 12th the French flagship Languedoc had lost its bowsprint, all of its masts and its rudder. It was simply floating without being able to steer.

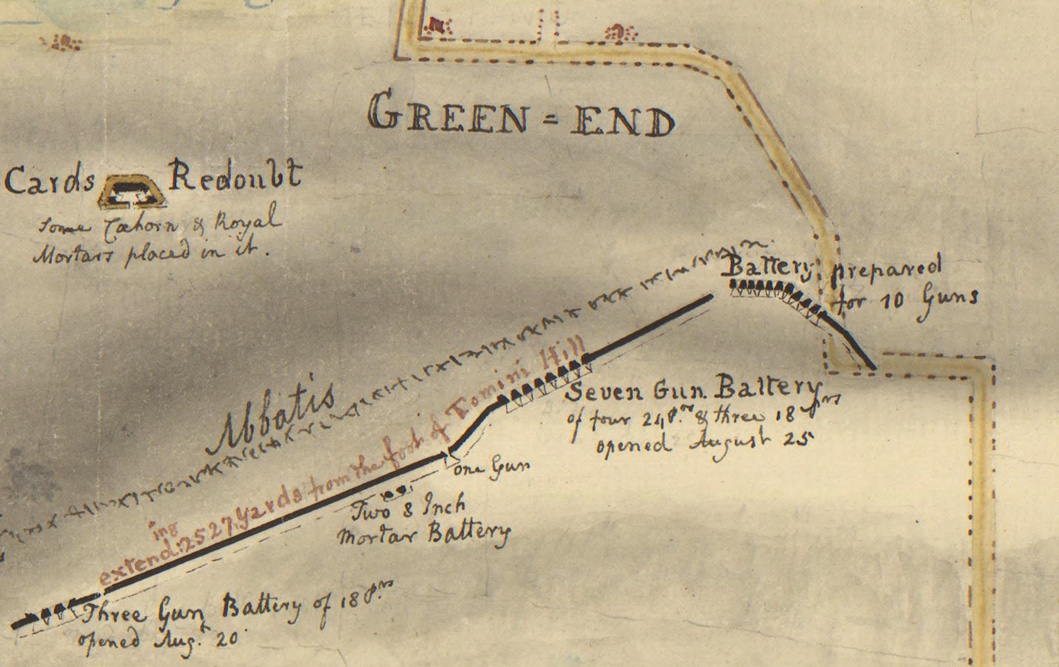

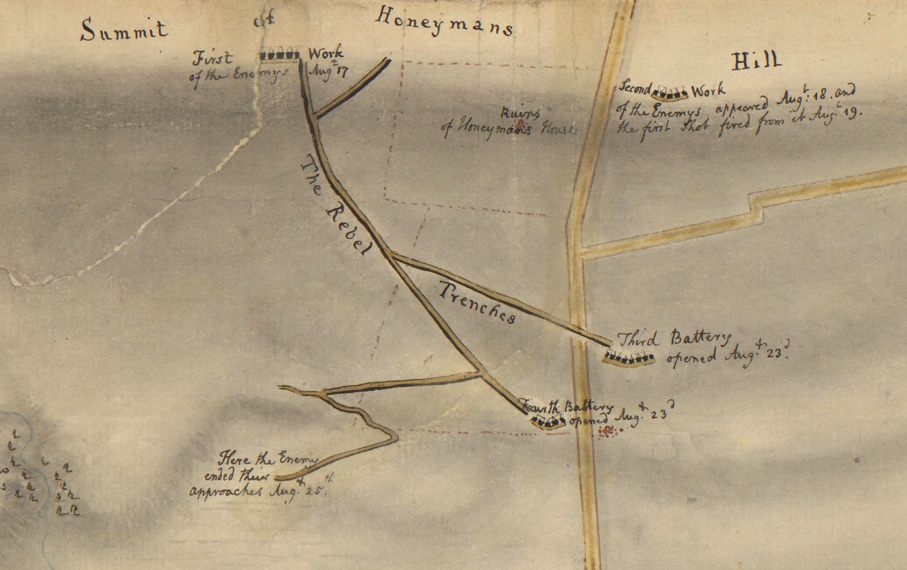

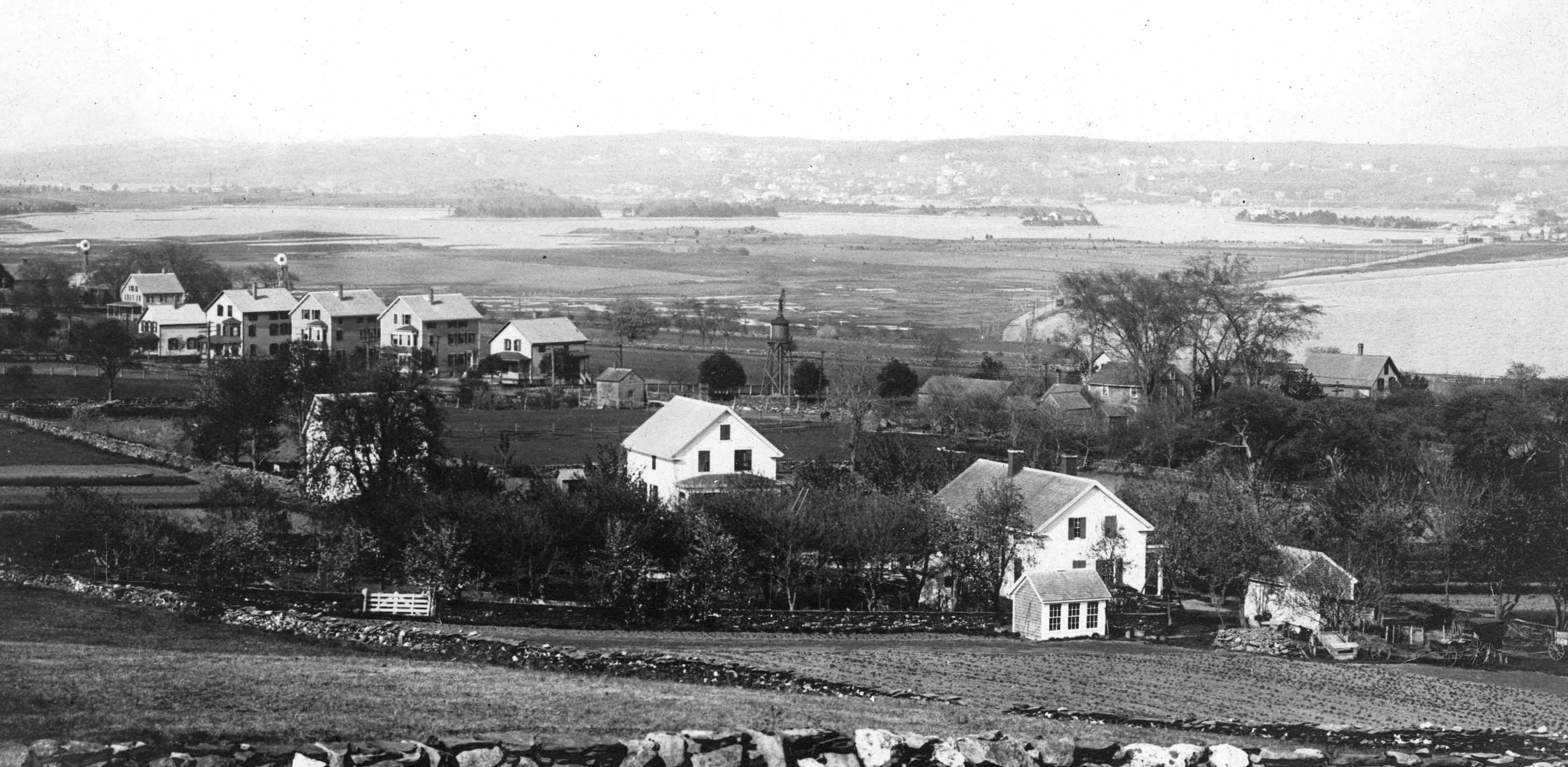

August 15, 1778, Americans open the Siege of Newport. The Americans needed to construct defensive works, so Sullivan marched them south with banners flying. By 5 PM they halted and pitched camp by Honeyman Hill in Middletown. This was a high point where the Americans could view the British lines. However the 20 day enlistments of many militia units were up and they left. Sullivan was waiting for new units to arrive. Col. Paul Revere commanded the Boston artillery train and John Hancock was major general of the 3000 member Massachusetts militia.

August 16, 1778, Americans were preparing a four cannon battery on the western slope of Honeyman Hill. The British opened fire as the fog lifted, so the Americans worked on the trenches and battery in the dark or fog.

August 20, 1778, d’Estaing’s battered ships return to Narragansett Bay. D’Estaing informs Sullivan he must immediately leave for Boston for repairs. His order from the King of France was to protect his fleet.

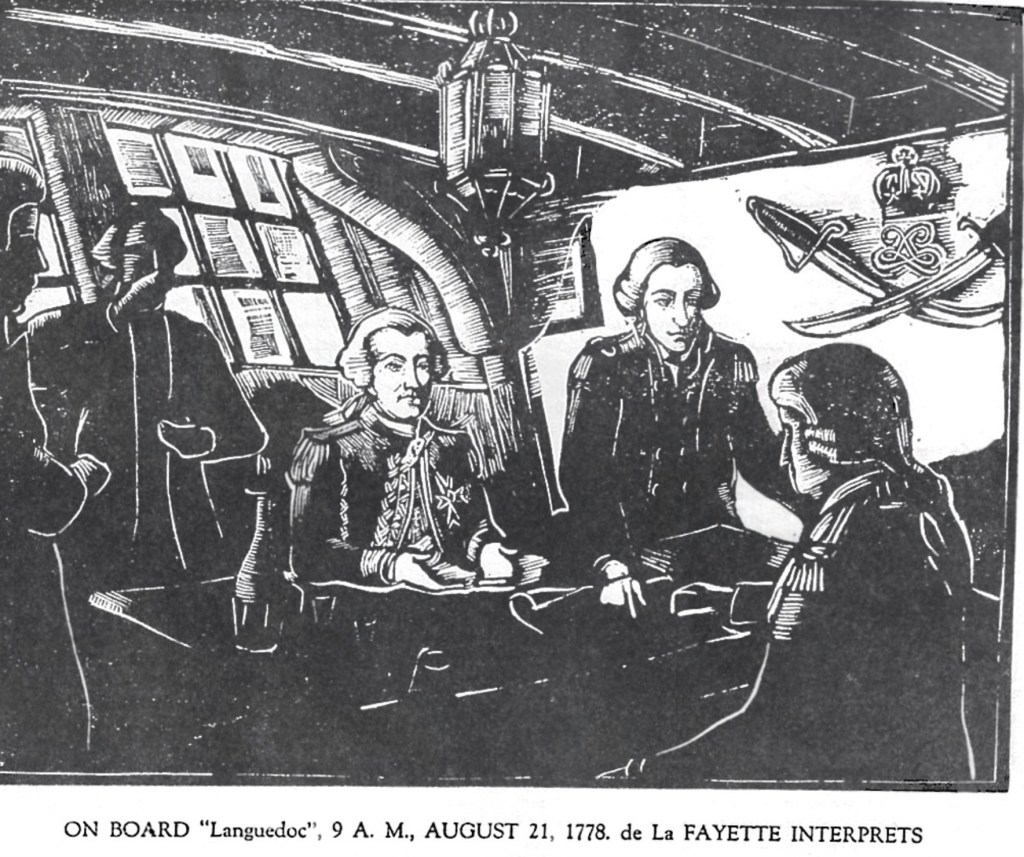

August 21, 1778, Sullivan sends Nathanael Greene, Lafayette and Col John Langdon to board the Languedoc – d’Estaing’s ship and talk with d’Estaing. D’Estang still decides to have the fleet sail for Boston.

August 24, 1778, Sullivan receives word that a British naval force is on its way to Newport. Sullivan and his officers prepare for a quick withdrawal. At a council of war there is unanimous agreement to move the troops to the Portsmouth end of the island to wait for the French return. Sullivan advocated for a gradual and orderly retreat.

August 25, 1778. All unnecessary baggage was removed off the island. Work on the trenches stopped. Volunteers began to leave in large numbers. Revere and his artillery and Hancock and his Massachusetts militia are among those leaving the island. Hancock asks for a letter of introduction to talk to d’Estaing in Boston. Mortars and heavy cannon were taken off the island.

August 27, 1778, Sullivan sends Lafayette to Boston to determine when d’Estaing would come back to Rhode Island. Lafayette made the 70 mile trip in just 7 hours. By this time Sullivan had lost 3,000 volunteers through illness or decisions to leave the island.

August 28, 1778, American council of war decides to withdraw Patriot forces to defensive positions around Butts Hill. They would be close to the ferry landings if they needed to withdraw completely. By 8PM the soldiers put down their tents and marched out with Greene commanding the West column up West Main Road and Glover leading the other column up East Main.

Resources: This timeline is based on Christian McBurney’s book – The Rhode Island Campaign.