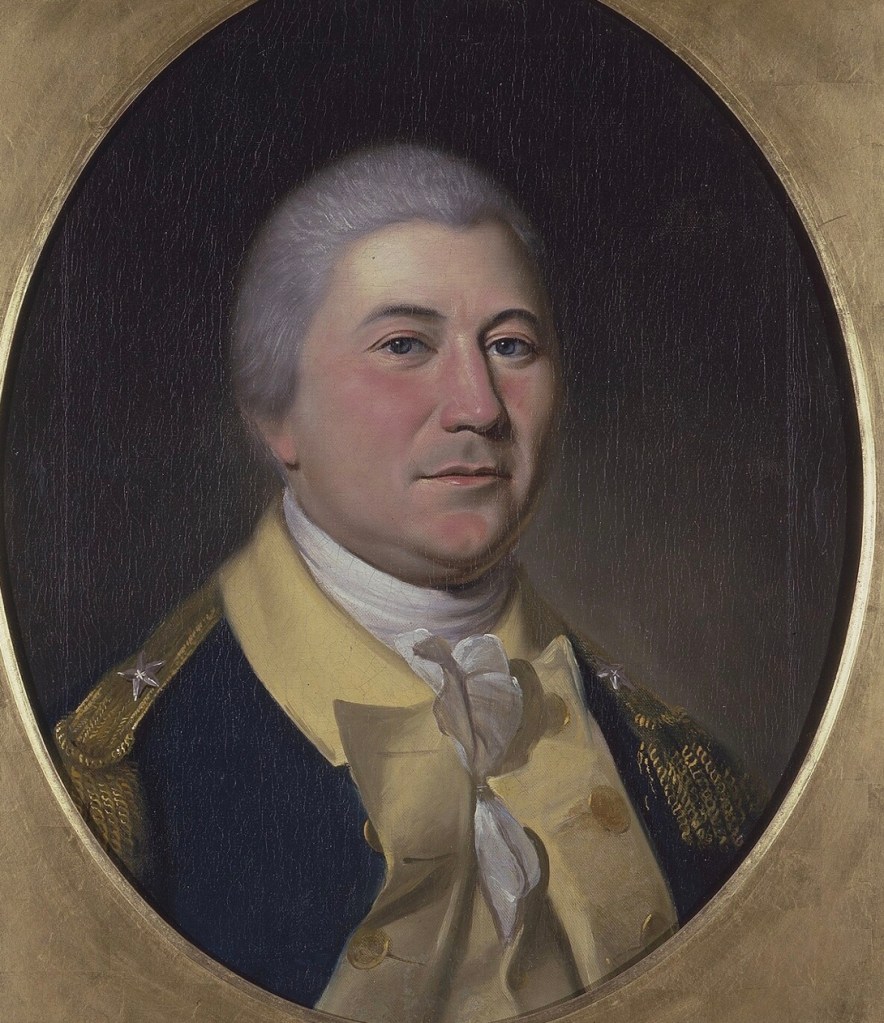

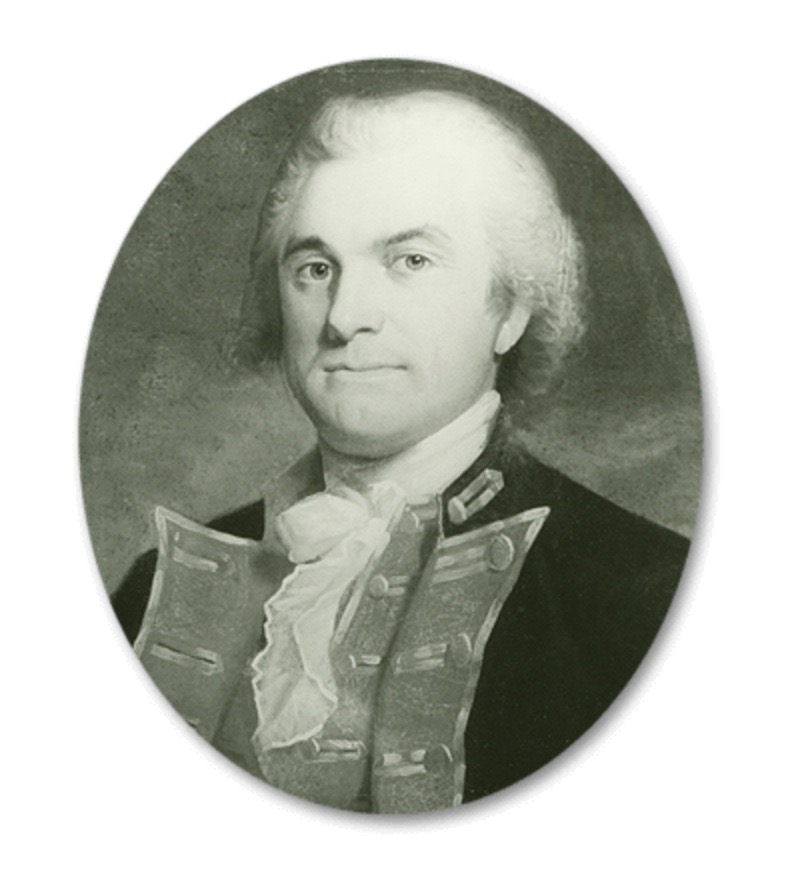

Major General Nathanael Greene: He was born into a Quaker family in the Coventry area of Rhode Island. Greene worked as the resident manager of the Coventry Iron Works, working at the forge making large ship anchors and chains until you enlisted in the army. Although of Quaker background, he was active early in the colonial fight against British revenue policies in the early 1770s. He was self educated and valued books and learning – especially about military topics. He helped establish the Kentish Guards, a state militia unit, but a limp prevented you from joining it. Rhode Island established an army after the April 1775 Battles of Lexington and Concord. Greene was tapped to command it. Later that year he became a general in the new Continental Army. He served under George Washington in the Boston campaign, the New York and New Jersey campaign, and the Philadelphia campaign. He was appointed quartermaster general of the Continental Army in 1778, but reserved the right to command troops in the field. Before the Battle of Rhode Island, he was placed in charge of the right flank of the army. He had the reputation of being one of Washington’s most talented Generals. In 1780 Washington put him in charge of the Army’s Southern Campaign and he fought through the end of the War.

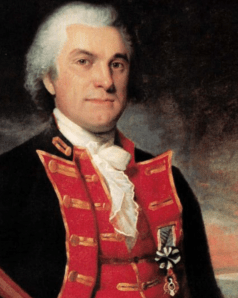

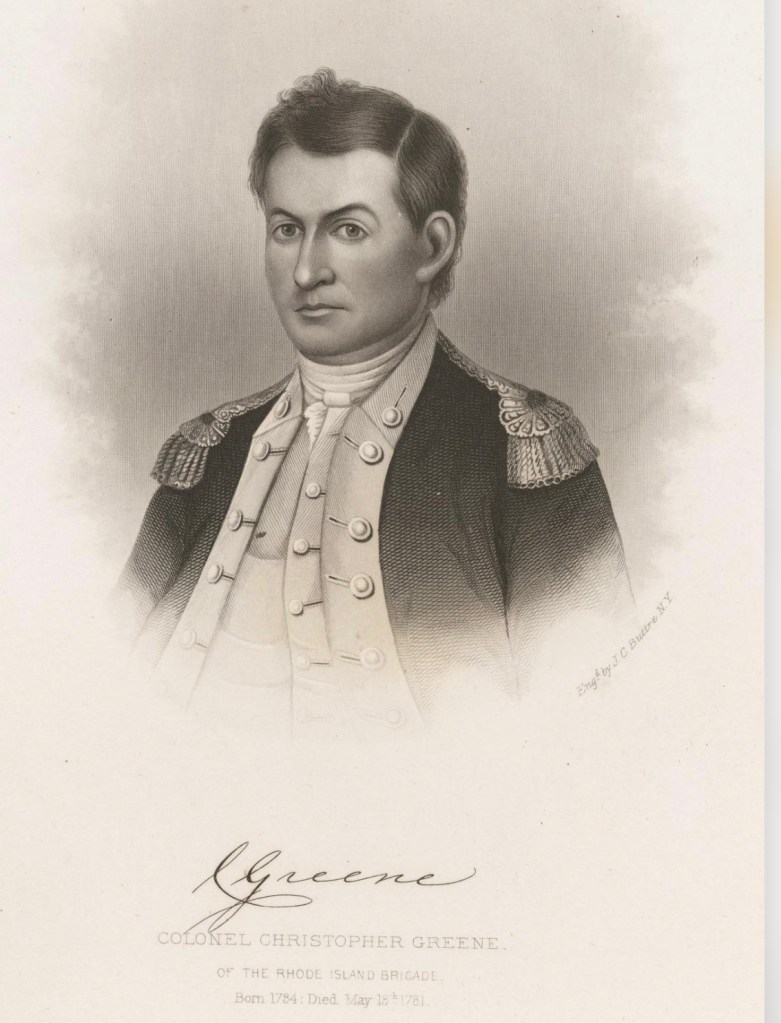

Col. Christopher Greene: He had long Rhode Island roots. He was a descendent of Rhode Island founder Roger Williams. Christopher Greene was a distant cousin of Nathanael Greene. Before the Revolutionary War, Christopher Greene served in the Rhode Island legislature from 1771 to 1772. With Nathanael he helped organize a militia unit, the Kentish Guards. After the Battles of Lexington and Concord he joined the army around Boston. He voluntarily joined Col. Benedict Arnold and was promotion to lieutenant colonel. He was with Arnold at the siege of Quebec and was was captured. He was released in August 1777 and joined the Continental Army for the Philadelphia Campaign. He was given command of the First Rhode Island Regiment. He defended Fort Mercer on the Delaware River. Washington agreed to enlist blacks and indigenous men to fill the ranks of a Rhode Island Regiment. The enlistments granted the soldiers their freedom if they served throughout the war. It benefited their owners with compensation. Christopher Greene was in charge recruiting, training and leading the 1st Rhode Island (the Black) Regiment. Colonel Greene died on May 14, 1781 at the hands of Loyalists by his headquarters on the Croton River in New York.

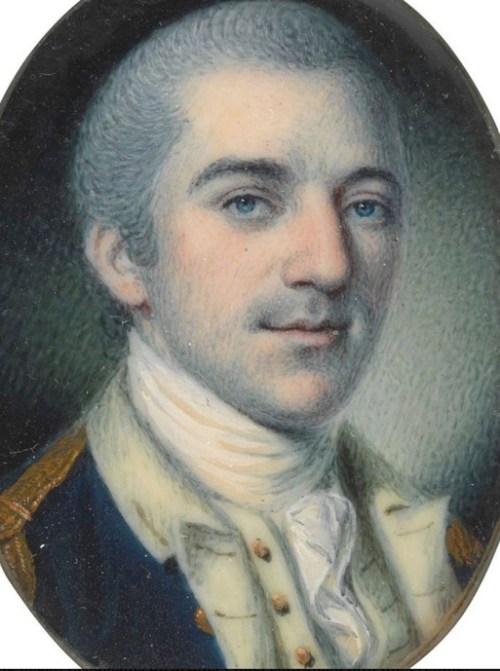

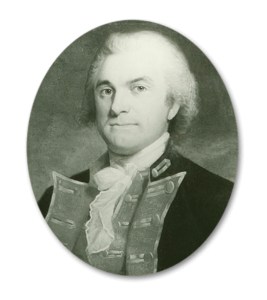

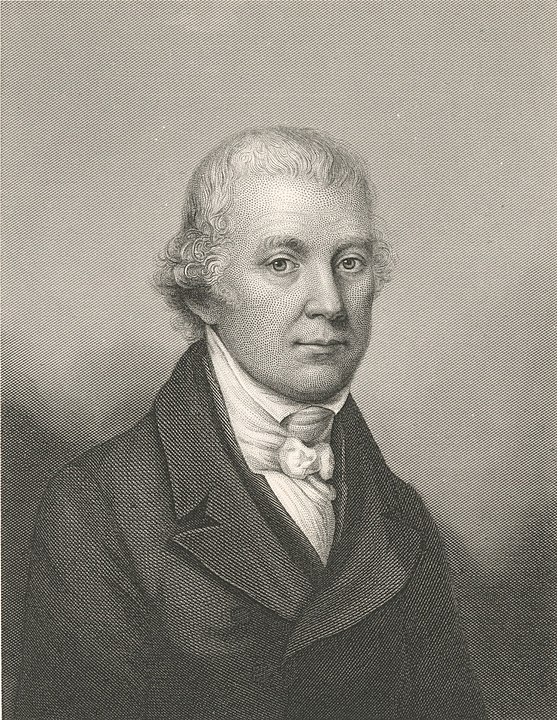

Col. Israel Angell: Angell came from one of the founding families of Providence. He served throughout the Revolutionary War. He was a major in Hitchcock’s Regiment at the beginning of the war and served with that regiment at the Siege of Boston. As the Continental Army was organized in 1776, Angell was part of the 11th Continental infantry. When Hitchcock was appointed brigade commander, he commanded the regiment. His regiment was re-named the 2nd Rhode Island Regiment on January 1, 1777. He was promoted to lieutenant colonel and shortly after to Colonel. He commanded the regiment following the death of Hitchcock. Angell was an experienced soldier who served at Valley Forge, the Siege of Boston, Brandywine, Red Bank, Monmouth and then the Battle of Rhode Island. At the Battle of Rhode Island he commanded 260 men. American General Nathanael Greene ordered Colonel Israel Angell’s 2nd Rhode Island Regiment to support Ward’s 1st Rhode Island Regiment. They were able to reach the key artillery redoubt before the British forces. He served in New York, but he retired from the army on January 1, 1781, after the two Rhode Island regiments were consolidated into a single regiment known as the Rhode Island Regiment.

Major Silas Talbot: He was born in Dighton, Massachusetts. He trained as a mariner and as a builder and made his home in Providence. In the aftermath of the burning of the Gaspee and the Boston Tea Party, Rhode Island merchants were alarmed. Independent militias were forming and he joined and was commissioned as a Lieutenant. He joined others in his company in learning military skills in a Providence warehouse, but he didn’t have any real military experience. On June 28, 1775 he answered the Rhode Island Assembly’s call to send units to Boston. He marched with his men to join the Second Rhode Island Regiment and by July 1, he was commissioned a captain. Talbot and the other 1200 men in the Rhode Island brigade took part in the Siege of Boston watching over the Red Coats but not in direct battle. His skills as a bricklayer came in handy as they built barracks on Prospect Hill. By April of 1776 the Siege was over and Rhode Islander Esek Hopkins, Commander in Chief of the Continental Navy, needed a crew to sail the ships home to Providence. Washington offered to loan Hopkins men from the Rhode Island Regiment and he switched from soldier to sailor. He was involved in the Rhode Island Campaign. As someone with experience as a mariner and builder, he helped to construct the flatboats that would take American forces to Portsmouth on August 9th of 1778. During the Battle of Rhode Island, Talbot led men in the early skirmishes on West Main Road. Talbot had success fighting on both land and sea. In 1779 he was made a Captain in the American Navy after he captured a British ship.

Major Samuel Ward: Ward was the son of a Rhode Island governor. His military career began when you were commissioned a captain in the Army of Observation in May, 1775, at the age of eighteen. He participated in Benedict Arnold’s attack on Quebec in December, 1775, under Lieutenant-Colonel Christopher Greene. He was taken prisoner by the British and released in August, 1776. He was promoted to the rank of major in the First Rhode Island Infantry and, between 1776 and 1778, served with his regiment at Morristown, New Jersey (1777); Peekskill, New York (1777); Red Bank (Fort Mercer) under Christopher Greene (1777); Valley Forge (1778); and the Battle of Rhode Island (1778). Ward retired from the Continental Army on January 1, 1781, when the 1st and 2nd Rhode Island Regiments were consolidated into the Rhode Island Regiment. Ward was the grandfather of Julia Ward Howe

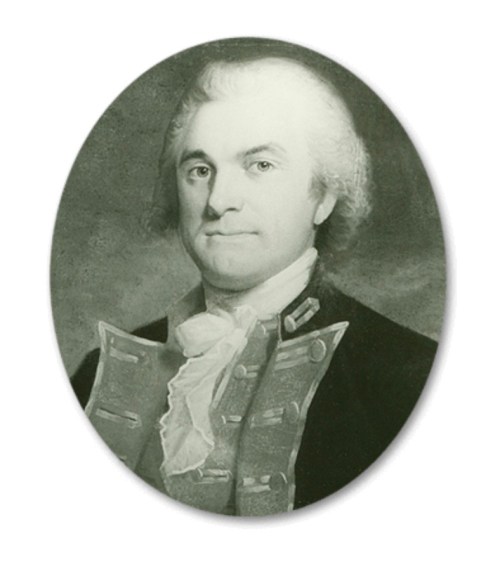

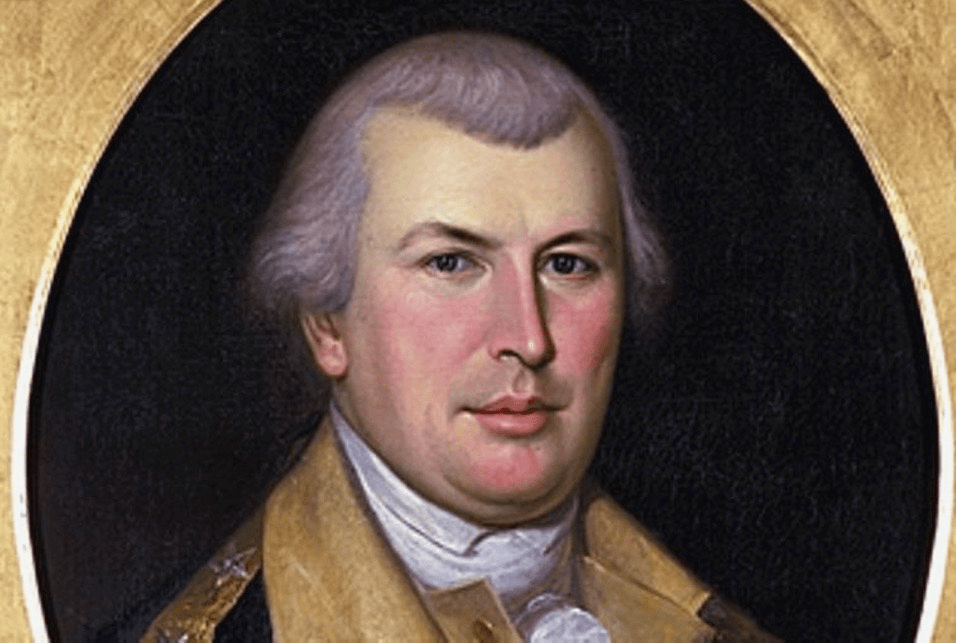

General James Mitchell Varnum: Varnum was born in Massachusetts but he came to Rhode Island to attend Brown. He married and set up a law practice in East Greenwich, and he independently studied military affairs. In October of 1774 he became a founder and commander of the Kentish Guards a imilitia company in East Greenwich, Rhode Island. With the fighting at Lexington and Concord, Varnum started to march his militia to Boston but they were not needed and headed home. In May 1775 Varnum was commissioned as a Colonel of the 1st Regiment of Rhode Island. By 1776 the regiment was folded into the Continental Army under the command of Brigadier General Nathanael Greene, Varnum’s friend. From Varnum and his Rhode Islander troops took part in participated major engagements including the Battle of Bunker Hill and the Battle of Rhode Island. Varnum and his men were at Valley Forge. Varnum was another proponent of raising a regiment of black and indigenous soldiers. In March 1779, he retired from the Continental forces and accepted a commission as Major General of the Rhode Island militia. Upon returning home to East Greenwich he was elected to the Continental Congress in 1780.