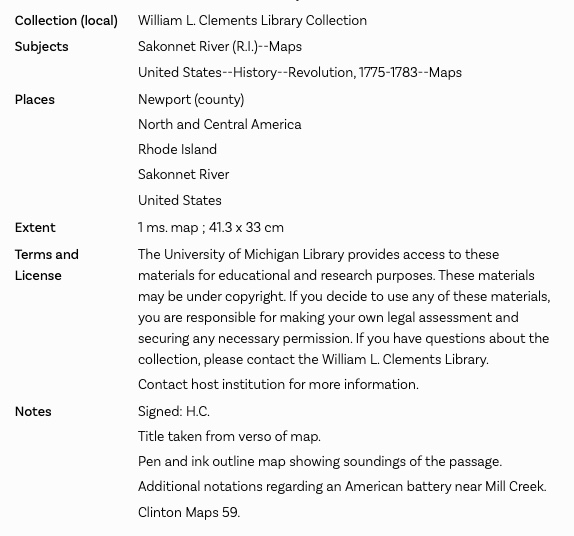

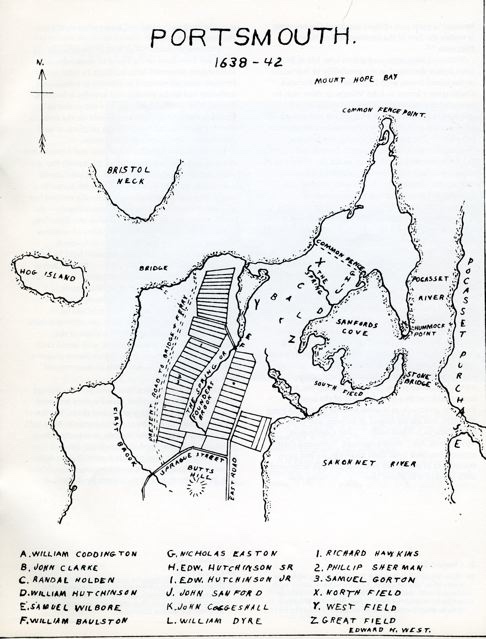

The Denison Map of the Battle of Rhode Island is filled with information. I generally look for specific pieces of information from this gem, but today I am going to methodically go through the information it provides. As I go through this map, I am comparing it to the map from the General Sullivan Collection that is in the state archives. I am noting that the handwriting and comments are very similar.

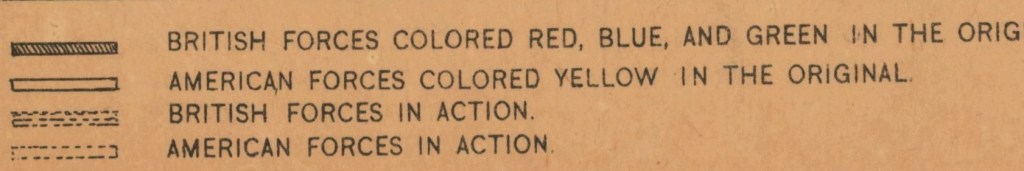

Looking at the Denison map in general there is a compass on the left hand side. There is a scale for two miles and there is a legend of sorts for the positions of the American commanders. The mapmaker lists himself as J. Denison “Scripsit” which means writer. The map covers the areas and dates involved in the “Rhode Island Campaign” – mainly Aquidneck Island and the surrounding waterways. Notes on the bottom of the map tell us that the original is at the Massachusetts Historical Society and that this version is a copy. A note at the bottom provides a legend for symbols in color in the original.

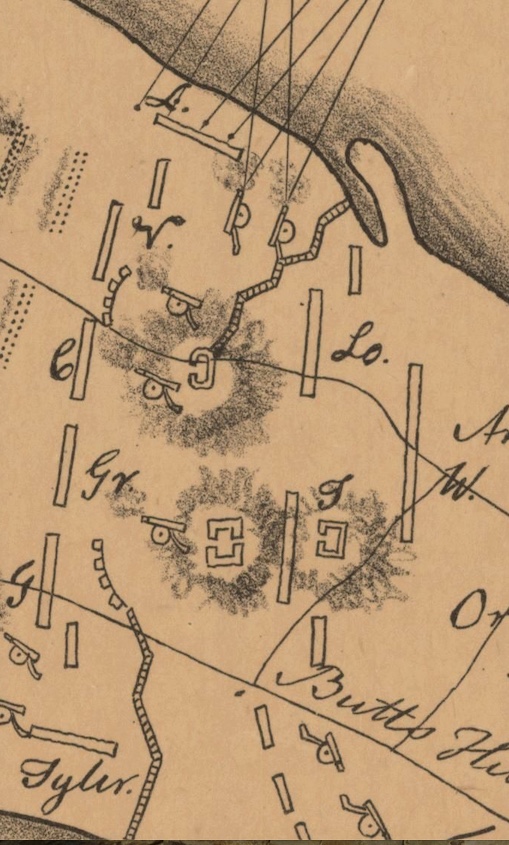

The legend for the battle positions is given at the bottom.

First Line:

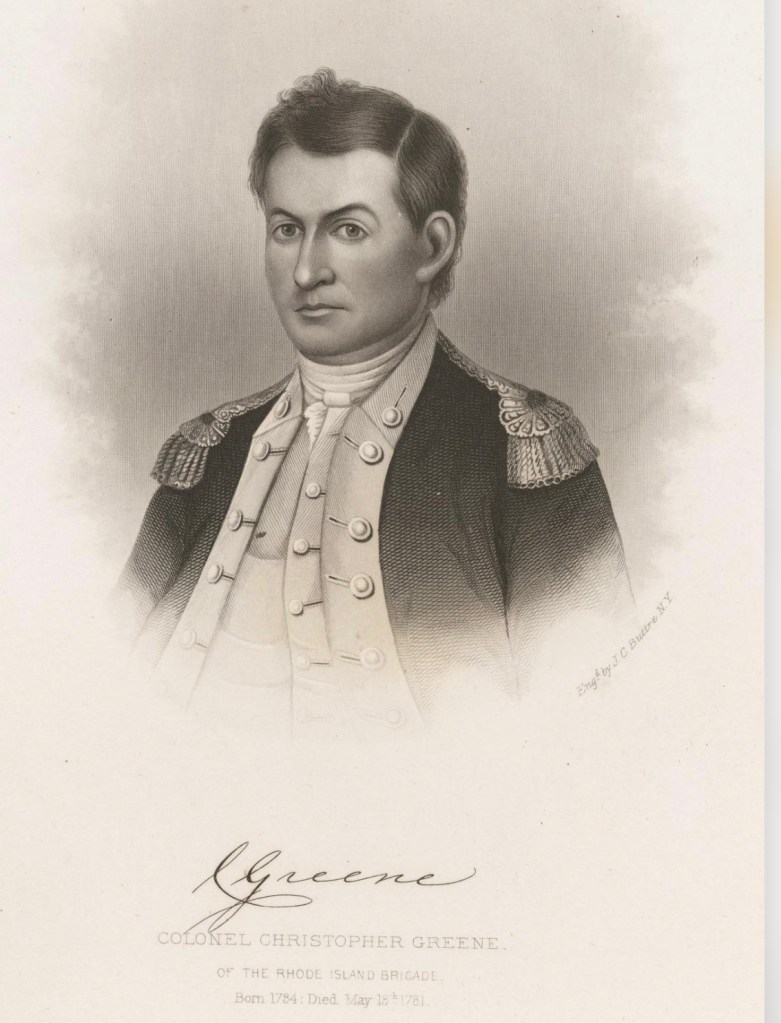

G is for Glover, Gr is for Greene, C is for Cornell, V is for Varnum.

Second Line: T is for Titcomb, L is for Lovell.

Reserve: W is West

Flanking Divisions: L is for Livingston and Tyler

The Archives map has no key, but it does have a compass and scale. The names of the commanders are written out, but the positions are the same as in the Denison map.

Comments comparison:

By Howland Ferry: Denison: Here the American Army landed August 9th 1778 beginning half after 6 o’clock A.M. and retreated the 30th in the evening.

By Howland Ferry: Archives: Here the American Army landed August 9th 1778 beginning half after 6 o’clock A.M. and retreated the 30th in the evening.

The comments close to Union Street about the beginning of the battle were the same. :

The comments between East Main and West Main are the same.

What is different is that the Denison map has notations on the French Fleet. These are absent from the Archives map:

On the Sakonnet: “French ships going out to join the French Fleet going to Boston, August 20, 1778.”

In Newport Harbor”. “French fleet going out in pursuit of the British Fleet August 10th 1778, which were then at anchor Near Point Judith.”

By Hog Island: “British ships firing on the American Troops in time of Battle August 29, 1778.”

There is no Author statement on the Archive’s map, but I believe both maps were drawn by J Denison. The Dennison map is more finished. The Archive map looks to be more a record taken at that time and the basis for the Denison map. Perhaps others were aware that these two maps are basically the same, but this was revelation to me. I am still trying to find out about the mapmaker, j Denison. I would appreciate any information about him. He is credited with many more maps through the years.