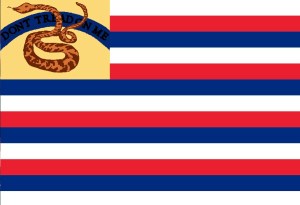

I have been exploring the stories behind some of the local Revolutionary War flags and this flag has led me to interesting areas of research. The “rattlesnake” emblem on it is very popular these days.

The first time I heard of Sullivan’s Guard was through Christian McBurney’s book on the Rhode Island Campaign. That gave me the name of one of the Guard members to research and his story will come in a later blog. This is a first article about the men of the Life Guard.

Searching for general information on Sullivan’s guard and the flag was difficult. Reproductions of the flag are available to buy and it is also known as the Tri-Colored Stripes with Rattlesnake Union. One source describes the flag:

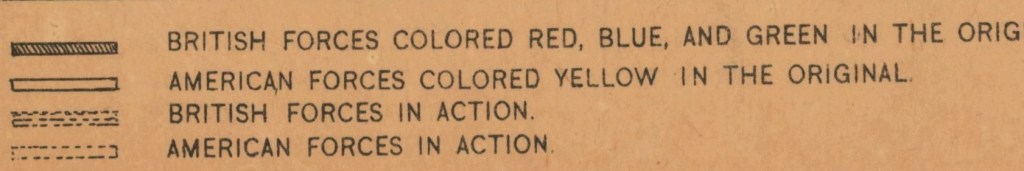

“This flag’s field consists of the tri-colored striped flag as designed by Arthur Lee in 1779: thirteen alternating white, red, then blue stripes from top to bottom, ending with a white stripe. But rather than having a canton of stars, this flag has an image of a coiled rattlesnake on a buff colored background for the canton. Behind the rattlesnake is a motto: “Dont Tread On Me” in black lettering on a curved, rainbow-shaped blue band that connects the hoist edge with the third stripe from the top (blue).” https://www.motherbedford.com/Flags27.htm

What was the Life Guard? Who was part of it? What was their service at the Battle of Rhode Island and elsewhere? These are the questions I have been trying to answer.

With the help of Military Historian John Robertson, I was able to get the names of some of the Life Guard soldiers. I have been searching through the Fold3 database for records of the men and some of the pension applications were very helpful in answering some of those questions

“I William Wilkinson of Providence State of Rhode Island on oath do testify that I served in the Rhode Island Brigade of State Troops in the War of the Revolution from July 1777 to March 16, 1780. I stated in a former deposition that I fully recollected that Ford Westcott served during a part of that period in General Sullivan’s Guard, and my impressions are that he was a non-commissioned officer. The Soldiers of the Guard were some of them taken from the Brigade and some were enlisted especially for that service, but were all enrolled in the Brigade. I have no knowledge at what period said Wescott enlisted, but know that the term of enlistment not only of the Brigade but of the guard did all expire on the 16th day of March in the several years of 1770, 1779, 1780. I further testify that for more than forty years I was intimately acquainted with Capt. Man who commanded the Guard and like many other old soldiers have fought our battles over again – and as said Westcott resided in Providence, his name was mentioned by said Man as a good soldier.”

William WILKINSON SEPT 16,1836, Providence (US, Revolutionary War Pensions, 1800-1900)

Let’s look at one question at a time.

What was the Life Guard? “The Soldiers of the Guard were some of them taken from the Brigade and some were enlisted especially for that service, but were all enrolled in the Brigade.” Christian McBurney writes that the guard may have been modeled on George Washington’s Life Guard. In 1776 Washington ordered Commanding officers of each regiment to select four men from each regiment who would form his personal guard. He wanted them good men, sober, five feet eight to five feet 10 and cleanliness was desired.

Their job was to protect Washington, the cash and to gather and keep the orders Washington gave..

In researching the names of Sullivan’s guard, I have found they came from at least two of the state militia units – the Pawtuxet Rangers and Crary’s. Some were designated by their commanders and some enlisted themselves.

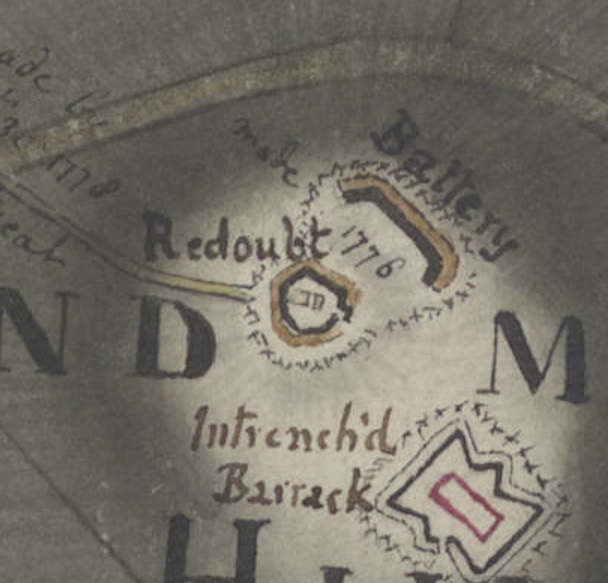

More information on the Sullivan’s Life Guard will come in future blogs. The flag may not have been at the Battle of Rhode Island. One source says it originated in 1779. Another flag site said it was at the Battle of Rhode Island.