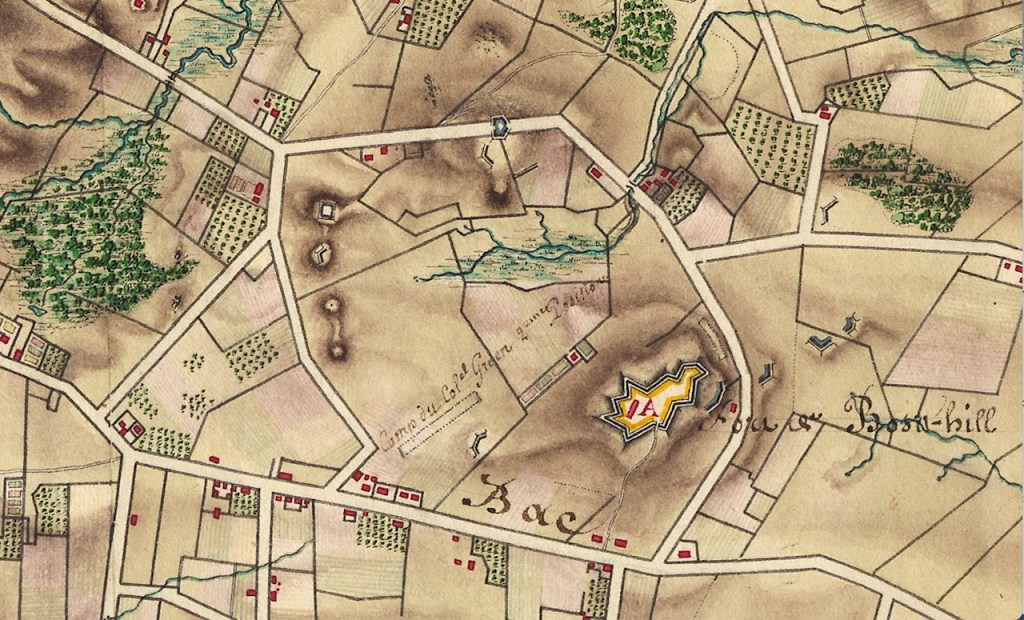

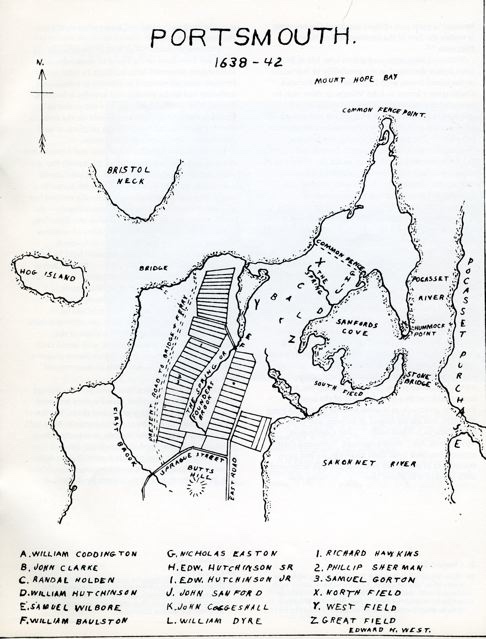

Some places in Portsmouth have changed names over the years, but Common Fence Point was the name used in 1638 and it is the name used today. A Borden family genealogy gives us the root cause for the name: “To the northeast of the spring a neck of land extends about two miles, which was nearly separated by creeks, marshes and the town pond from the rest of the island. This strip of land, called by the natives Pocasset Neck, was set off by the settlers as a common by running a fence from the south end of the pond to a cove on the east side of the island. This common was called the fence common, to distinguish it from the lands outside to the south and west of it, which were all common; and the north point then received the name of common fence point. “(1)

The original settlement of Portsmouth took a pattern that was familiar to the English – homes were in a central village location and their animals grazed on common land around the homesteads. Recording how each family branded their animals was very important with their stock intermingled in the commons. While this may have been a good pattern the first year when they needed to be close together for safety, this land use soon gave way to larger scattered farm lots which included their homes.

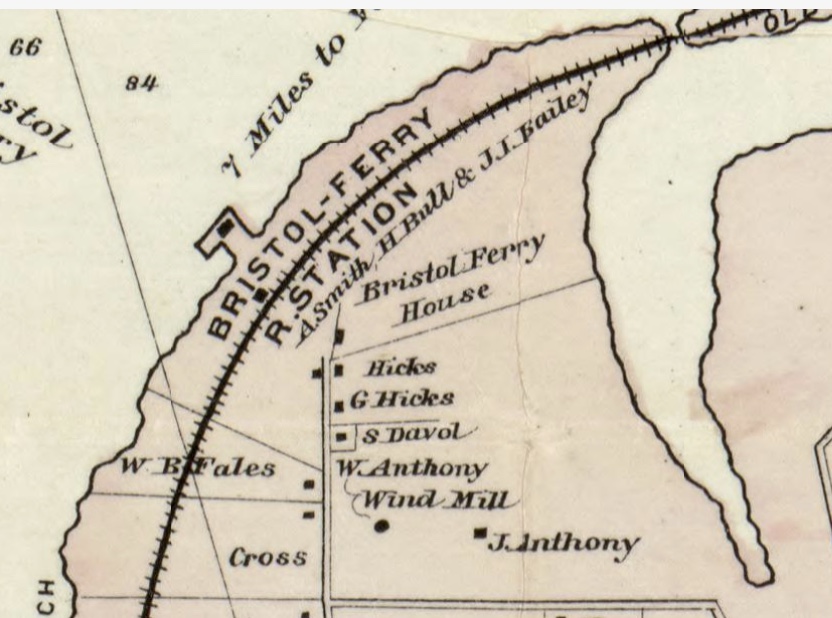

The 1849 Hammett Map shows Abner Chace holding Common Fence Point and the Chace (or Chase) family seemed to own pieces of the Point for many years. In 1865 a charter was granted to several men to build and operate the Rhode Island Oil and Guano Company on Common Fence Point.

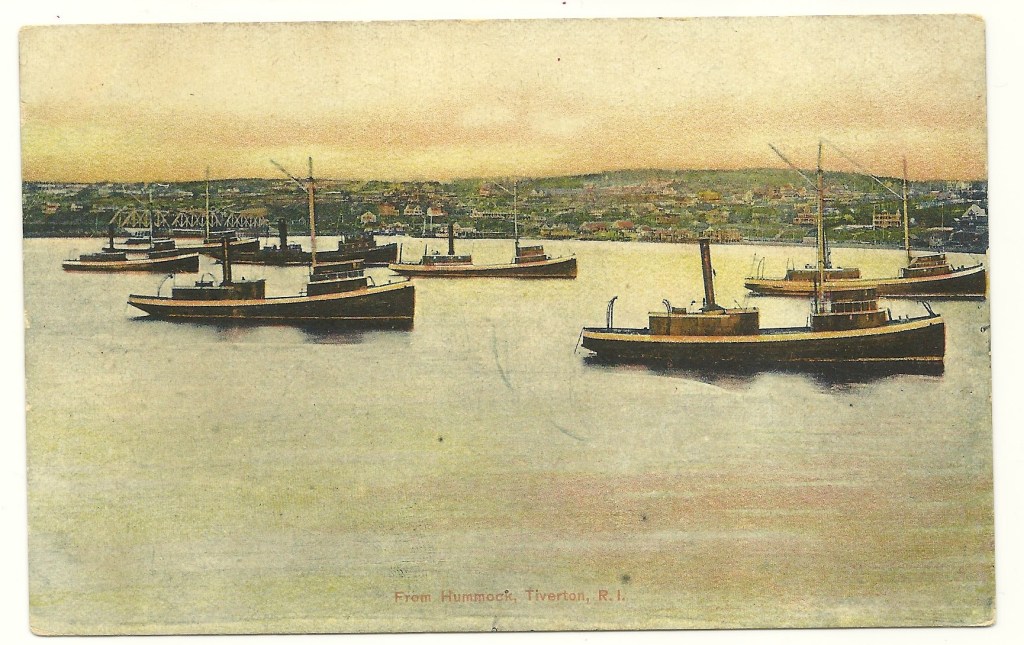

Pogy boats

By 1900 part of Common Fence Point held the largest fish factory in the country. The Tiverton based Church Brothers – Daniel, Nathaniel, Joe, Jim, Isaac, Fisher and George went into business together in 1870. They commissioned the Herreshoff boatyard in Bristol to build the first fishing steamer – the Seven Brothers. At first they were fishing for food, but they realized that fish oil and fertilizer from the pogy fish (menhaden) had potential for profit. They brought a menhaden processing factory in Maine, dismantled it and rebuilt it on Common Fence Point. The complex cookhouse was 35 ft square and there were two large dinning rooms to feed three hundred workers. A large building held sleeping quarters and a net mending area. A cooper made barrels for transporting the oil and there were boat shops. The Church Brothers Fisheries barn burned in 1928 and that was the last of the Church facilities on Common Fence Point.

Common Fence Point gradually developed into a community. At first many of the houses served as summer homes, but they gradually became occupied year round. The Common Fence Point Improvement Association has been active in the community since he 1950s and continues to serve the residents of Common Fence Point with music programs, classes, activities for children and as an Arts Center.

(1) Historical and Genealogical Record of the Descendants as Far as Known of Richard and Joan Borden, who Settled in Portsmouth, Rhode Island, May, 1638: With Historical and Biographical Sketches of Some of Their Descendants H.B. Weld, 1899

(2) The Descendants of Thomas Durfee of Portsmouth RI-Vol. 1, by Wm. Reed. 1902.

(3) Genealogical Records of the Descendants of Thomas Brownell compiled by George Brownell, New York, 1910.