October 25, 1779: The British evacuate Newport to consolidate their position in New York.

On July 11, 1780 a squadron of French warships approached Newport. It was not the first time the French came to Newport’s waters. The Treaty of Alliance with France was signed on February 6, 1778. On July 29, 1778 a French squadron sailed into Narragansett Bay. It created a military alliance between the United States and France against Great Britain. On the American side it was negotiated by Benjamin Franklin, Silas Deane, and Arthur Lee. This treaty stipulated that France and America would not negotiate a separate peace with Britain and that American independence would be a requirement before any peace treaty was signed. The Rhode Island Campaign in 1778 was the first French and American operation under the treaty. This joint action ended prematurely when damage from a storm took the French out of the Campaign.

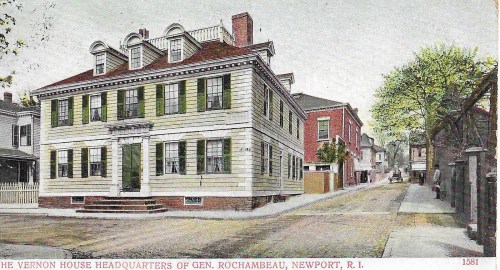

In 1780 the “Expedition Particuliere” or Special Expedition would be a successful alliance. In July of 1781 Rochambeau’s French troops would leave Newport to join Washington’s army for the ultimate victory over the British in Yorktown.

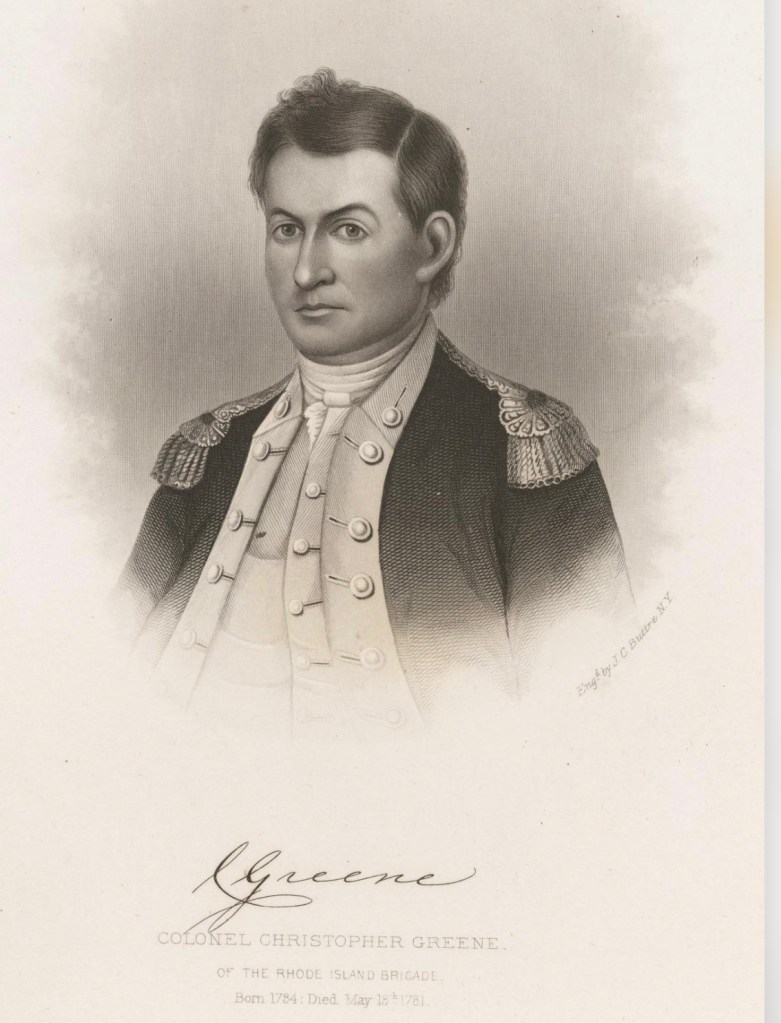

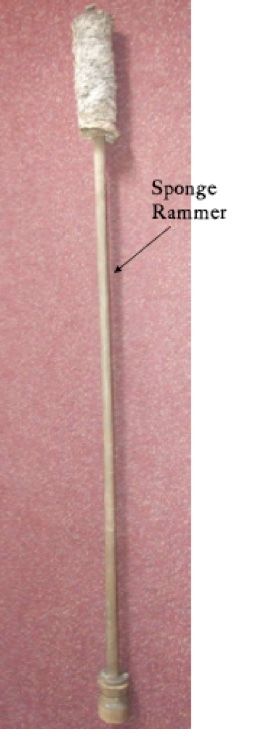

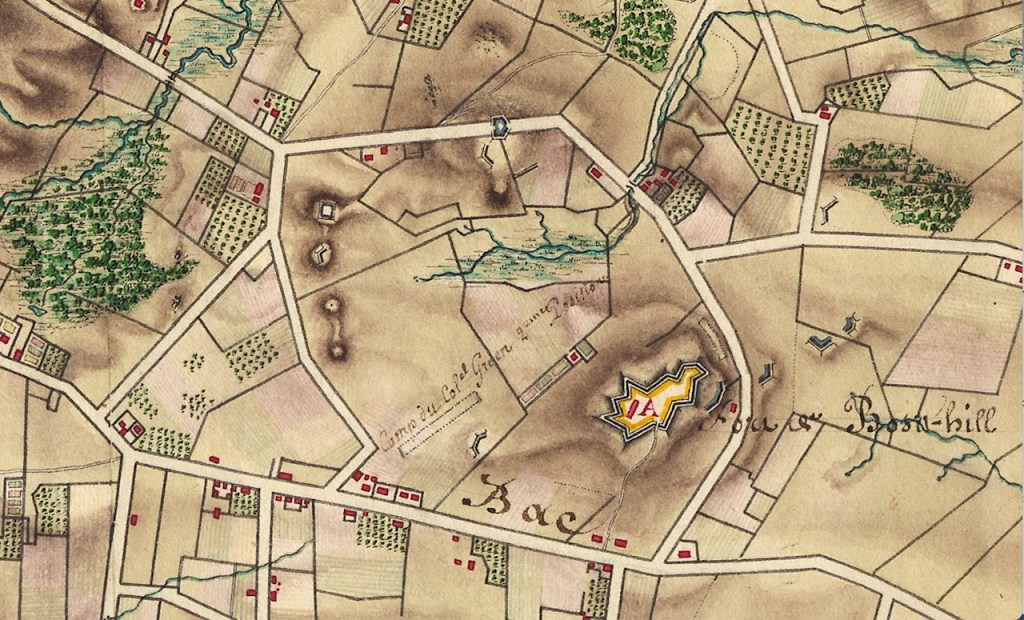

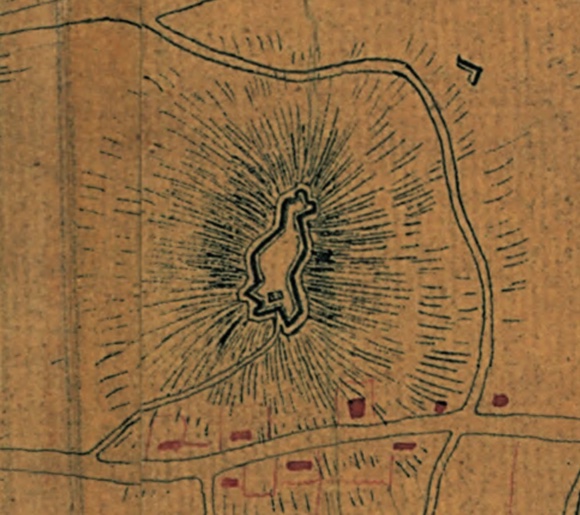

The French arrived in Newport in July of 1780. Most of the forces wintered in Newport except the Lauzun Legion which camped in Connecticut. Rochambeau was very skillful in handling his troops and the Americans began to appreciate their presence. Where the British had demolished defenses, the French engineers worked on rebuilding them. Major General William Heath’s diary for September of 1780 notes that “The batteries were strengthened, a very strong one erected on Rose-Island, and redoubts on Coaster’s-Island: the strong works on Butt’s-Hill (were) pushed..” A few days later he would remark: “The French army continued very busy in fortifying Rhode-Island: some of their works were exceedingly strong, and mounted with heavy metal.” We know from orderly books (daily records) that the American militiamen were aiding the French masons as they enlarged and fortified Butts Hill Fort.

On March 6, 1781, three months before the French army departed from Newport, General Washington visited Count de Rochambeau to consult with him concerning the operation of the troops under his command. Washington was hoping to encourage Rochambeau to send out his fleet to attack New York City. In an address to the people of Newport, Washington expressed gratitude for the help of the French:

“The conduct of the French Army and fleet, of which the inhabitants testify so grateful and affectionate a sense, at the same time that it evinces the wisdom of the commanders and the discipline of the troops, is a new proof of the magnanimity of the nations. It is a further demonstration of that general zeal and concern for the happiness of America which brought them to our assistance; a happy presage of future harmony…appeasing evidence that an intercourse between the two nations will more and more cement the union by the solid and lasting times of mutual affection.” (Quote taken from New Materials for the History of the American Revolution by J. Durant. Henry Holt, New York, 1889.)

Washington left Newport and journeyed overland to Providence. On his departure he was saluted by the French with thirteen guns and again the troops were drawn up in line in his honor. Count de Rochambeau escorted Washington for some distance out of town, and Count Dumas with several other officers of the French army accompanied him to Providence. We know that General George Washington travelled by Butts Hill Fort on the old West Main Road on his way to the Bristol Ferry because the West Road was the customary route from Newport to the ferry. Washington’s aide, Tench Tilghman, recorded the fee for the Bristol Ferry on the expense book.

In May of 1781 Washington and Rochambeau met again, this time in Weathersfield, Connecticut. This meeting confirmed the joining of the forces and the march South.

The French left Newport in stages:

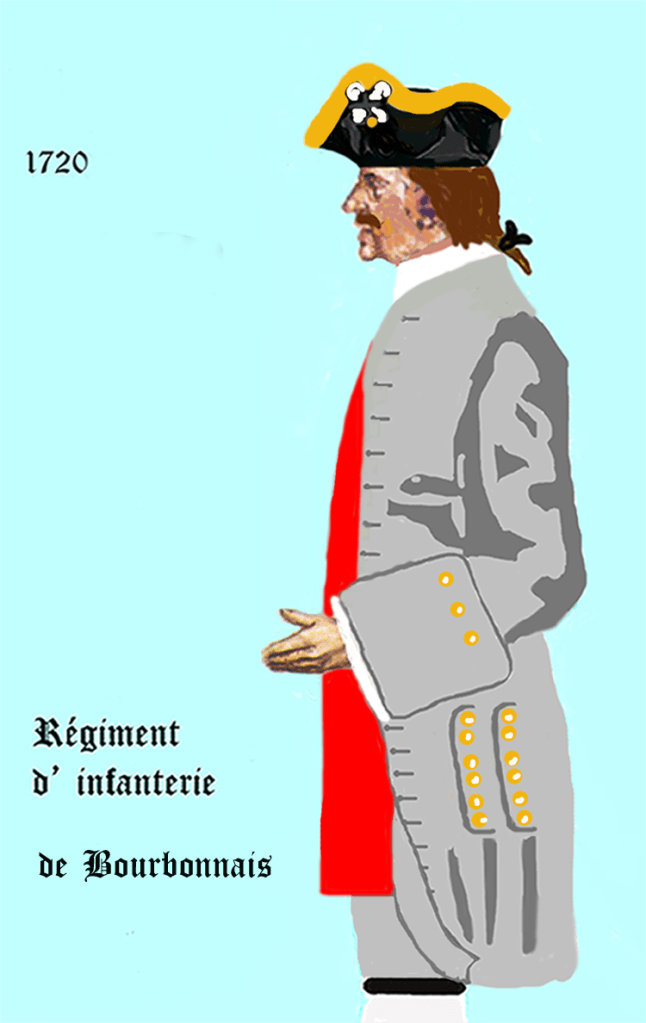

Regiment Bourbonnois under the vicomte de Rochambeau, left on June 18

Regiment Royal Deux-Ponts under the baron de Vioménil, left on June 19

Regiment Soissonnois under the comte de Vioménil, left on June 20

Regiment Saintonge under the comte de Custine, left on June 21.

Brigadier General de Choisy was left behind in Newport with some French troops. He sailed with Barras’ fleet to the Chesapeake area in August. In the summer of 1781, General Rochambeau’s French Army joined forces with General Washington’s Continental Army, With the French Navy in support, the allied armies moved hundreds of miles toward victory in Yorktown, Virginia in September of 1781.

Resources:

https://www.nps.gov/waro/learn/historyculture/washington-rochambeau-revolutionary-route.htm

By Robert Selig, PhD. for the Washington-Rochambeau Revolutionary Route Resource Study & Environmental Assessment, 2006.

https://digitalcommons.providence.edu/cgi/viewcontent.cgi?article=1018&context=ri_history. Visit of George Washington to Newport in 1781 – French E. Chadwick. 1913

Loughrey, Mary Ellen. France and Rhode Island, 1686-1800. New York, King’s Crown Press, 1944.